Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.280842

A 55-year-old man with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who did not require home oxygen, as well as hypertension, was brought to our emergency department after being found unresponsive at home.

Student Discussion

Student Discussion Document (pdf)

Nicholas Gau and Mitchell G. Scott*

Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

*Address correspondence to this author at: Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110. Fax 314-362-1461; e-mail [email protected]

Case Description

A 55-year-old man with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that did not require

home oxygen, as well as hypertension, was brought to our emergency department after being

found unresponsive at home. The patient’s family said he was in his usual state of health until

today, when they noticed increased dyspnea consistent with his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. They believed it was caused by recent overexertion cleaning tools with various

chemicals. His breathing became worse as the day progressed, and he was found overnight to be diaphoretic and unresponsive, prompting a 9-1-1 call. The family denied sick contacts, recent

travel, and toxin ingestion.

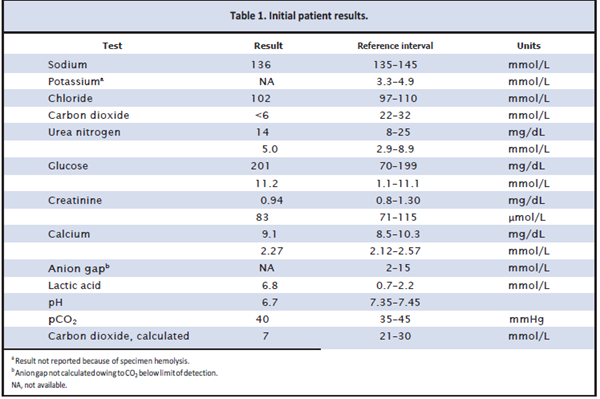

Examination in the emergency department showed a chronically ill man in severe distress, with rapid shallow respirations, prompting immediate intubation. He exhibited no purposeful movements and no response to noxious stimuli, but his pupils were responsive to light. Vital signs included a heart rate of 86 beats/min; respirations, 26 breaths/min; blood pressure, 196/112 mmHg; and oxygen saturation, 95% by pulse oximetry. Point-of-care glucose was 176 mg/dL (reference interval, 70–199

mg/dL). An electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm without ST segment changes. Initial laboratory testing included a basic metabolic panel, lactic acid, and arterial blood gases (Table 1). A white blood cell count was 20.8 K/mm3 (3.9 –9.9 K/mm3).

Using the calculated total CO2 from the arterial blood gas, the anion gap was 27 mmol/L (2–15 mmol/L). Serum osmolality was 329 mOsm/kg (275–300 mOsm/kg), with a calculated osmolal gap of 52 mOsm/kg. Other initial blood testing included a hepatic function panel, lipase, troponin I,

B-type natriuretic peptide, and acetaminophen; all were unremarkable. Urinalysis was notable for 1+ketones and 2+ protein. Computed tomography of the head and abdomen showed no acute abnormalities. A chest radiograph showed a normal cardiac silhouette and no evidence of pneumonia, effusion, or pneumothorax.

Questions to Consider

- How is the anion gap calculated, and what is its significance?

- How is an osmolal gap calculated, and what is its significance?

- What is the differential diagnosis for a high anion gap metabolic acidosis?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the July 2018 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.280842

Copyright © 2018 American Association for Clinical Chemistry