Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.283283

An infant with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and inadequate nutrition was evaluated. The patient was the offspring of a consanguineous (first cousin) Syrian couple, born at term in Syria after an unremarkable pregnancy. His neonatal course was unremarkable.

Student Discussion

CCS November 2018

Lizbeth Mellin-Sanchez1 and Neal Sondheimer1,2*

1Division of Clinical and Biochemical Genetics, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada; 2The Department of Paediatrics, The University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

*Address correspondence to this author at: 555 University Avenue, Toronto, ON M5G1X8. Fax 416-813-4940; e-mail [email protected]

Case Description

An infant with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and inadequate nutrition was evaluated. The patient was the offspring of a consanguineous (first cousin) Syrian couple, born at term in Syria after an unremarkable pregnancy. His neonatal course was unremarkable. At the age of 7 months he presented with intermittent diarrhea, fever, and poor feeding. His symptoms progressed, and at 11 months (upon migration to Canada) he was admitted to the hospital for weight loss, decreased

urine output, fever, and the loss of skills such as babbling, rolling over, or sitting without support. At the time of admission, he was only taking maternal breast milk.

On physical examination, he was pale and irritable. There were no dysmorphic features. He had limited antigravity movements, hepatomegaly, and a systolic ejection murmur. His initial chemistry and hematology evaluation included hemoglobin level of 45 g/L (reference interval, 100–140 g/L), with moderate microcytosis and macrocytosis, mild polychromasia, and schistocytes. His reticulocyte count was 168 X 109/L (reference interval, 10–100 X 109/L). Plasma vitamin B12 was<62 pmol/L

(reference interval, 119–1164 pmol/L), and plasma folate was 33.9 μmol/L (reference interval, >23 μmol/L). A nasopharyngeal swab was positive for rhinovirus.

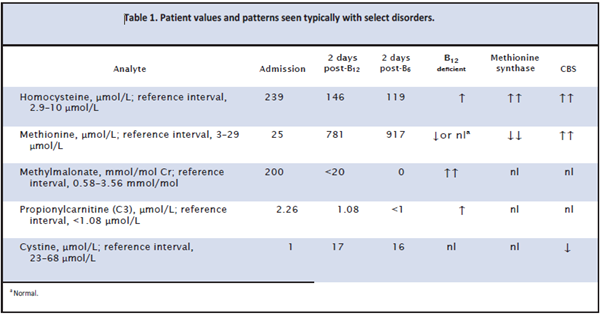

Metabolic studies were obtained (Table 1). The total and free carnitine concentrations were normal. Urine organic acids identified an increased methylmalonate peak of>200 mmol/mol creatinine (reference interval, 0.58– 3.56 mmol/mol creatinine), and his acylcarnitine profile included increased propionylcarnitine of 2.26 μmol/L (reference interval, <1.08 μmol/L). The total plasma

homocysteine (Hcy) was increased at 239 μmol/L (reference interval, 2.9–10 μmol/L). Methionine concentration in plasma was normal at 25 μmol/L (reference interval, 3–29 μmol/L), and the cystine concentration was 1 μmol/L (reference interval, 23–68 μmol/L).

He was treated with packed red blood cells, iron supplementation, fortified formula through nasogastric feeds, and an intramuscular injection of cyanocobalamin (1000 μg).

Forty-eight hours after B12 administration and transfusion, his urine methylmalonate had normalized

(Table 1). The methionine was now greatly increased at 781 μmol/L. His acylcarnitine profile had normalized. His total Hcy remained high at 146.1 μmol/L. He was started on vitamin B6 50 mg twice daily, and blood testing was repeated. These studies showed a sustained increase in total Hcy of 119μmol/L and a high methionine concentration of 917 μmol/L.

Questions to Consider

- What potential disorders are suggested by the increases in serum methylmalonate and plasma homocysteine concentrations?

- What is the most likely diagnosis given the increased methionine and plasma homocysteine concentrations after vitamin B12 administration?

- What testing could be done to confirm the patient’s diagnosis?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the November 2018 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.283283

Copyright © 2018 American Association for Clinical Chemistry