Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.275628

A primary care physician telephoned to inquire about the clinical significance of low alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in a 54-year-old man, which led to an investigation for the cause of the low ALP, a biochemical abnormality that is known to be underappreciated

Student Discussion

Student Discussion Document (pdf)

Ravinder Sodi1,2* and David Hall3

1Department of Biochemistry, Blood Sciences, Royal Lancaster Infirmary & Furness General Hospital, University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust, Lancaster, UK; 2Lancaster Medical School, University of Lancaster, Lancaster, UK; 3Medwyn Medical Practice, Carnwath, Lanarkshire, UK.

*Address correspondence to this author at: Department of Biochemistry, Blood Sciences, Royal Lancaster Infirmary & Furness General Hospital, University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust, Lancaster, LA1 4RP, UK. Fax +44-01524-519703; e-mail [email protected] or [email protected].

Case Description

A primary care physician telephoned to inquire about the clinical significance of low alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in a 54-year-old man, which led to an investigation for the cause of the low ALP, a biochemical abnormality that is known to be underappreciated (1). The man was a military veteran currently working as a fireman. His records showed that he had a history of multiple

fractures throughout his life, including the right clavicle at age 12 years, the left tibia with inflammation of the patellar ligament at the tibial tuberosity (Osgood–Schlatter disease) at 13 years, and the right ring finger when he was 15 years old. He reported severe foot pain starting in 2006 at age 44 years. At age 50 years, 2 separate radiographic examinations of the foot showed osteonecrosis of the second metatarsal (Freiberg disease) and loss of bone density. Around this time, he also reported a 2-week history of severe pain under the heel of his right foot. All these were observed despite no reported external injury or trauma. His current medications include corticosteroid nasal spray (mometasone furoate), dihydrocodeine, baclofen, cocodamol, quinine sulfate, propranolol, gabapentin, and diazepam.

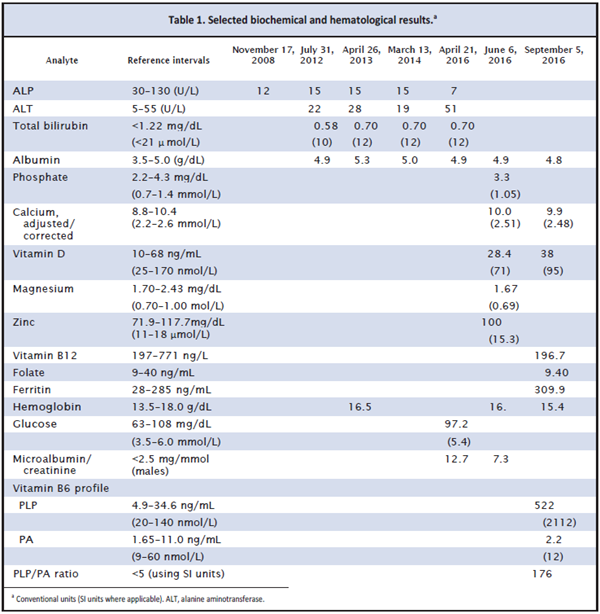

As shown in Table 1, the man’s records revealed that his ALP had been low on 5 separate occasions in

the past 8 years. There was no biochemical evidence to suggest metabolic bone disease, hypothyroidism, or any other electrolyte disturbance, and he was vitamin D replete. Magnesium and vitamin B12 levels were marginally low, whereas zinc was within reference limits. Ferritin was raised, likely because of the acute phase response owing to fractures. Microalbuminuria

was reported on 2 occasions. There was no evidence of diabetes mellitus. Given his history of fractures, we sent a plasma sample to a specialist laboratory for a vitamin B6 profile. The pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP) concentration was strikingly increased for a non–vitamin B6-supplemented patient, giving a raised PLP-to-pyridoxic acid (PA) ratio (reference, <5 using SI units) (2).

Questions to Consider

- What are potential causes of low ALP activity in blood (hypophosphatasemia)?

- How should hypophosphatasemia be investigated?

- Which clinical condition is associated with hypophosphatasemia and raised PLP concentration?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the April 2018 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.275628

Copyright © 2018 American Association for Clinical Chemistry