Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.284042

A 12-year-old boy with refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was transferred to our hospital for compassionate treatment with gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO; MylotargTM).

Student Discussion

Student Discussion Document (pdf)

Merih T. Tesfazghi, Christopher W. Farnsworth, Stephen M. Roper, Ann M. Gronowski, and

Dennis J. Dietzen*

Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

*Address correspondence to this author at: Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, One Childrens Place, Room 2N68, Box 8116, St. Louis, MO 63110. Fax 314-286-2892; e-mail [email protected]

Case Description

A 12-year-old boy with refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was transferred to our hospital for compassionate treatment with gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO; MylotargTM). Before transfer, the patient had received 2 courses of salvage chemotherapy, after which bone marrow biopsy was negative for the disease. A plan for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation during his third cycle was halted because of disease recurrence.

On admission, the patient had leukemic infiltrates in his lungs, skin, distal esophagus, and gastric mucosa.

He was profoundly immunocompromised, neutropenic, anemic, and thrombocytopenic. Despite persistent fever, daily blood cultures performed at an outside hospital and on admission at our hospital were negative. The patient was treated with a comprehensive panel of antibiotics without a significant change in his persistent fever.

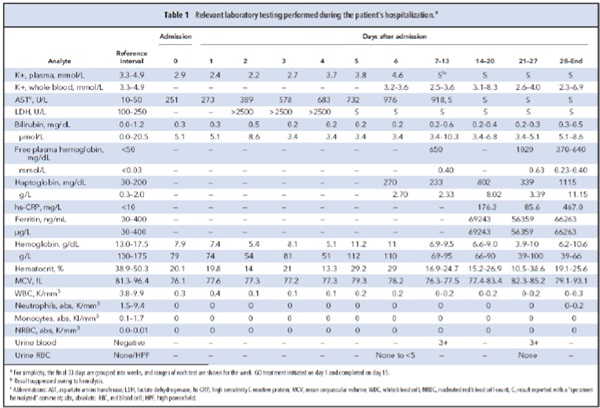

A day after admission, the patient began a 15-day cycle of GO therapy. On day 5, the laboratory began

receiving visibly hemolyzed specimens with increased hemolysis indices. Consequently, results from multiple biochemical tests were suppressed according to laboratory protocol (Table 1). The laboratory was contacted to help determine whether the hemolysis was in vivo or in vitro.

Questions to Consider

- What is the fate of free hemoglobin released in vivo?

- What laboratory parameters are useful to distinguish in vivo from in vitro hemolysis?

- Is this patient‘s hemolysis likely in vivo or in vitro?

- How is GO involved with hemoglobin and haptoglobin clearance?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the December 2018 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.284042

Copyright © 2018 American Association for Clinical Chemistry