Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.294140

A 60-year-old female patient with a history of chronic pain and headache presented to the Pain Management Clinic for follow-up assessment of her prescribed medications, as well as to determine the patient’s suitability for enrollment in the medical cannabis program.

Student Discussion

Student Discussion Document (pdf)

Mark A. Cervinski1* and Paul J. Jannetto2

1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon NH and The Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH; 2Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

* Address correspondence to this author at: Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, One Medical Center Drive, Lebanon, NH 03756. Fax +603-650-4845; e-mail [email protected]

Case Description

A 60-year-old female patient with a history of chronic pain and headache presented to the Pain Management Clinic for follow-up assessment of her prescribed medications, as well as to determine the patient’s suitability for enrollment in the medical cannabis program. The patient’s chronic pain and headache were secondary to traumatic brain injury sustained in a motor vehicle accident approximately 2 years before her appointment. The patient also was afflicted by chronic pain in her right arm due to nerve damage associated with surgery for de Quervain tendonitis. Following the motor vehicle accident, the patient had been evaluated at a multidisciplinary traumatic brain injury clinic and had been prescribed Tylenol #4 (acetaminophen 300 mg/codeine 60 mg) up to a maximum of 4 times daily for pain, and lorazepam (1 mg every 8 h as needed) for anxiety and insomnia.

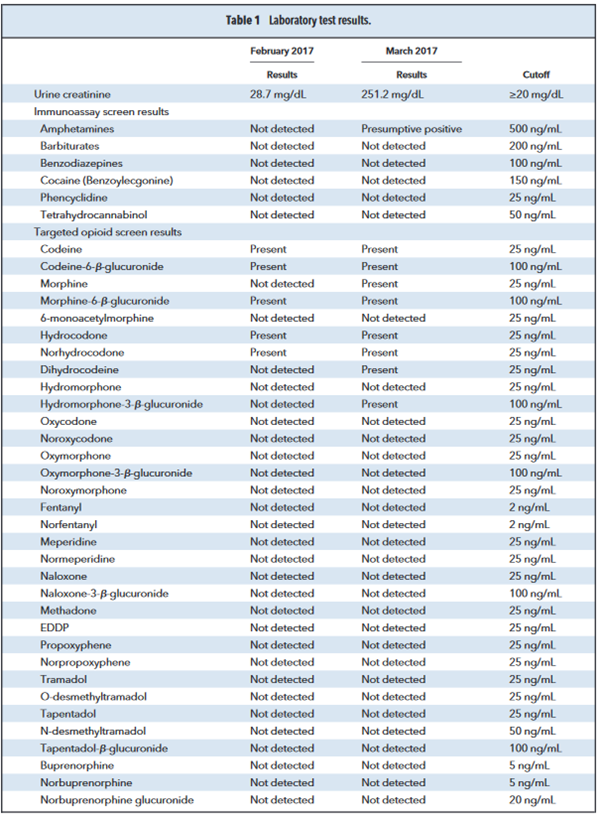

To determine the patient’s suitability for the medical cannabis program, the patient was required to submit a urine sample for drugs of abuse testing. Analysis of the sample was performed by a combination of immunoassay (amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, benzoylecgonine, carboxy-tetrahydrocannabinol, and phencyclidine) and high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry (opioids).

Following review of the patient’s urine test results the clinician contacted the laboratory for assistance with the interpretation of the opioid results. A review of the immunoassay screens only demonstrated presumptive positive results for the amphetamine class; however, reflexive confirmatory testing via liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for amphetamines (amphetamine, methamphetamine,

phentermine, methylenedioxyamphetamine, methylenedioxymethamphetamine, pseudoephedrine/

ephedrine) was negative (Table 1).

The high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry results were more complex and demonstrated the presence of codeine, codeine-6-β-glucuronide, morphine, and morphine-6-β-glucuronide, which were consistent with the use of codeine (Table 1) (1, 2). However, the analysis also unexpectedly revealed

the presence of hydrocodone, norhydrocodone, dihydrocodeine, and hydromorphone-3-β-glucuronide (Table 1).

References

- Snyder ML, Melanson SE. Drug addiction or false conviction? Clin Chem 2014;60:

1480 –3.

- Reisfield GM, Chronister CW, Goldberger BA, Bertholf RL. Unexpected urine drug

testing results in a hospice patient on high-dose morphine therapy. Clin Chem 2009;

55:1765– 8.

Questions to Consider

- What are the metabolic pathways and products associated with the metabolism of codeine?

- Can manufacturing impurities of codeine play a role in of the interpretation of these test results?

- What additional testing would be helpful to discern between compliance with the prescribed codeine and undisclosed use of additional opioids?

- Are all the results of the initial testing consistent with the prescribed medications?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the February 2019 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.294140

Copyright © 2019 American Association for Clinical Chemistry