Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.223115

A 54-day-old infant of Asian descent presented with jaundice. He first started appearing yellow a few weeks after birth. His pediatrician initially recommended increasing sunlight exposure. At subsequent visits, the pediatrician recommended stopping breastfeeding. Despite these interventions, the infant's jaundice persisted and his stools became pale.

Student Discussion

Student Discussion Document (pdf)

Sanjiv Harpavat,1* Sridevi Devaraj,1,2 and Milton J. Finegold1,2

1Department of Pediatrics and; 2Department of Pathology, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX.

*Address correspondence to this author at: Clinical Care Center 1010, 6701 Fannin St., Houston, TX 77030. Fax 832825-3633; e-mail [email protected].

Case Description

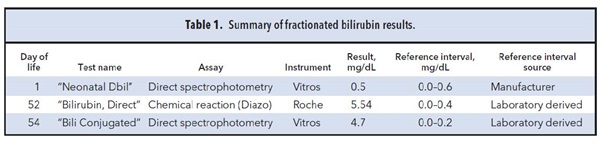

A 54-day-old infant of Asian descent presented with jaundice. He first started appearing yellow a few weeks after birth. His pediatrician initially recommended increasing sunlight exposure. At subsequent visits, the pediatrician recommended stopping breastfeeding. Despite these interventions, the infant’s jaundice persisted and his stools became pale. At 52 days of life (DoL), he had a serum bilirubin measured, and the reported “Bilirubin, Direct” concentration of 5.54 mg/dL (reference interval, 0.0–0.4 mg/dL) prompted an immediate referral (see Table 1 for a summary of laboratory results).

The infant’s physical examination and evaluation results were most consistent with biliary atresia (BA). He had marked jaundice, with a reported “Bili Conjugated” of 4.7 mg/dL (reference interval, 0.0–0.2 mg/dL), as well as increased aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and γ-glutamyltransferase activities. He otherwise appeared well and had 2 newborn screens with results within reference intervals, making infectious or metabolic etiologies unlikely. Furthermore, protease inhibitor typing, chest radiograph, and abdominal ultrasound revealed no abnormalities, arguing against other liver-associated causes such as α 1-antitrypsin disease, Alagille syndrome, and choledochal cyst.

There was one laboratory result, however, that was inconsistent with BA: his newborn conjugated bilirubin concentration, reported as “Neonatal Dbil.” In our experience, infants with BA have newborn direct or conjugated bilirubin concentrations that exceed their birth hospital’s derived reference interval (1). In contrast, this infant had a reported “Neonatal Dbil” concentration of 0.5 mg/dL on DoL 1, which was within the birth hospital’s reported reference interval of 0.0–0.6 mg/dL. The bilirubin was measured using a Vitros analyzer, and the reference interval was derived by the manufacturer based on “40 apparently healthy neonates” (2).

Because infants with BA treated earlier have the best outcomes, we continued the evaluation despite the discrepant newborn bilirubin concentrations. He promptly underwent liver biopsy, which showed fibrosis and bile duct proliferation characteristic of BA. Subsequent intraoperative cholangiogram confirmed the BA diagnosis. However, one important question still remained: how could the infant’s reportedly normal “Neonatal Dbil” concentration at birth be explained?

References

- Harpavat S, Finegold MJ, Karpen SJ. Patients with biliaryatresia have elevated direct/conjugated bilirubin levels shortly after birth. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1428–33.

- Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics. Instructions for use: VITROS chemistry products BuBc slides (bilirubin, unconjugated and conjugated). Version 6.0. Rochester (NY): Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Inc.; 2012.

Questions to Consider

- What is the difference between “Neonatal Dbil,” “Bilirubin, Direct,” and “Bili Conjugated”?

- How should reference intervals be established?

- Why are the reference intervals for the 3 tests in Table 1 different?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the February 2015 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.223115

Copyright © 2015 American Association for Clinical Chemistry