Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.176925

A 58-year-old woman in the depressive phase of bipolar disorder (BPD)3 type 1 enrolled in a clinical study of the efficacy of a new form of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for her depression, because ECT has not been commonly used for the treatment for BPD or depression. BPD is any of several mood disorders characterized by alternating episodes of depression and mania or by episodes of depression alternating with mild nonpsychotic excitement. BPD type 1 is distinguished from type 2 according to the severity of increased mood symptoms (1). At study enrollment, the patient reported severe sadness, a lack of motivation, fatigue, general malaise, feelings of guilt, and an increased need for sleep, but she had no suicidal or homicidal thoughts.

Student Discussion

Student Discussion Document (pdf)

Matthew Schmidt,1 Alina Sofronescu,2 Baron Short,1 Ziad Nahas,1 and Yusheng Zhu2*

Departments of 1Psychiatry and 2Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

*Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, 171 Ashley Ave., MSC

908, Suite 309, Charleston, SC 29425. Fax 843-792-0424; E-mail: [email protected].

Case Description

A 58-year-old woman in the depressive phase of bipolar disorder (BPD) type 1 enrolled in a clinical study of the efficacy of a new form of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for her depression, because ECT has not been commonly used for the treatment for BPD or depression. BPD is any of several mood disorders characterized by alternating episodes of depression and mania or by episodes of depression alternating with mild nonpsychotic

excitement. BPD type 1 is distinguished from type 2 according to the severity of increased mood symptoms (1). At study enrollment, the patient reported severe sadness, a lack of motivation, fatigue, general malaise, feelings of guilt, and an increased need for sleep, but she had no suicidal or homicidal thoughts. She had no history of galactorrhea. A physical examination revealed nothing outstanding except decreased tendon reflexes in the patellar and the achilles, and a small nodule on the closure site from a previous hysterectomy. A cranial computed axial tomography (CAT) scan was performed to assess for increased intracranial pressure before proceeding with ECT; no unusual findings were noted. Initial blood tests showed a serum sodium concentration of 135 mEq/L (135 mmol/L; reference interval, 135–145 mmol/L), a high triglyceride concentration [217 mg/dL (2.45 mmol/L); reference interval, <150 mg/dL (<1.69 mol/L)], and a VLDL cholesterol concentration of 43 mg/dL [1.11 mmol/L; reference interval, <30 mg/dL (<0.78 mmol/L)]. The results of a urine drug screen for amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepine, cannabinoids, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine were negative.

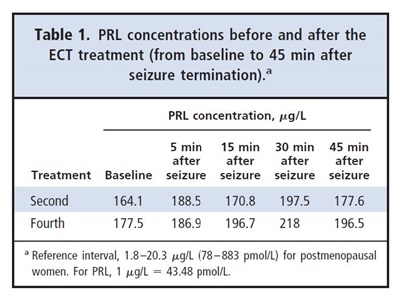

As per the study protocol, a baseline blood sample was drawn 5 min before treatment, and at 5, 15, 30, 45 min after seizure termination. Prolactin (PRL) concentrations were assessed from these blood draws during the second and fourth treatments of the study by means of a 2-site sandwich immunochemiluminometric assay (Siemens ADVIA Centaur® System). These assessments revealed unexpected and markedly increased

baseline PRL concentrations (Table 1). PRL concentrations increased further after ECT treatment and were still increased 45 min after the seizure. Although an increase in PRL concentrations after seizure initiation was expected, the increased baseline concentrations

were not, and a clinical investigation was conducted to determine the cause of the asymptomatic hyperprolactinemia in this patient.

Reference

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. p 169–72.

Questions to Consider

- How is PRL measured in clinical laboratories, and what analytical interferences can lead to a falsely increased PRL result?

- What are the physiological and pathologic conditions characterized by hyperprolactinemia?

- Can medications cause hyperprolactinemia?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the March 2013 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.176925

Copyright © 2013 American Association for Clinical Chemistry