Reliably diagnosing and treating diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is dependent on the quality of the laboratory and point of care (POC) testing performed. With regard to ketones, assessment of ketonemia has been supplanting urine ketone testing in both clinical practice and in recent diabetes guideline recommendations. There is an emerging consensus that blood beta-hydroxybutyrate (BOHB) measurement be used when assessing patients with possible DKA, with its availability as a point of care test only adding to its appeal. However, there are still a number of issues related to the measurement of blood ketones which have yet to be fully resolved (1). One such issue is that it is not known whether the POC or laboratory BOHB assays we currently use perform adequately for the clinical purpose to which they are intended. We therefore used existing authoritative diabetes guidelines to clinically determine the required performance of a BOHB assay by examining the test’s use in DKA diagnosis and treatment.

Regarding diagnosis of DKA, we used the pragmatic assumption that the blood BOHB assay should be able to perform sufficiently to reliably distinguish between a “normal” BOHB (<0.6 mmol/L) and “impending ketoacidosis” (1.6 to 2.9 mmol/L) and vice versa, or tell apart a value in the 0.6 to 1.5 mmol/L category (“ketonemia”) from one which is ≥3 mmol/L (“probable DKA”) and vice versa. A failure to distinguish between these non-adjacent diagnostic categories could lead to complete mismanagement of a patient. We found that an assay CV (combining within- and between day variation) of less than 21.5% at all relevant BOHB concentrations and zero bias was able to make this distinction with at least 99% probability, although if the assay had a significant bias then this could substantially reduce this CV such that, for example, a 0.8 mmol/L bias reduces the acceptable CV to just 10%.

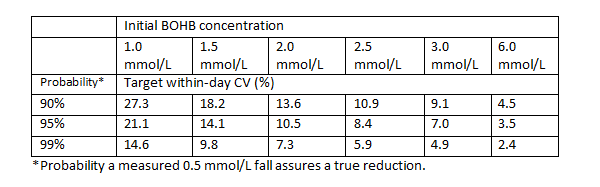

The second aspect was to use the recommended rate of fall in BOHB after DKA treatment has been started (at least 0.5 mmol/L/hr) to guide analytical performance. Again, a practical assumption was made that if sequential results indicated a fall of 0.5 mmol/L then it should truly be at least falling i.e. decreasing by more than zero mmol/L, rather than possibly rising. This criterion seemed destined to be the driver for assay performance given the relatively small changes being assessed, that two measurements were being made and that rounding results to one decimal place could introduce its own errors. Sure enough, the CVs were tighter (see table)., albeit these represented just within-day imprecision and were less likely to be affected by assay bias if the same instrument or meter was used.

These data can hopefully guide users as to the reliance they can place on blood BOHB measurement and inform manufacturers of the assay performance that is clinically required (2).

References

- Kilpatrick ES, Butler AE, Ostlundh L, Atkin SL, Sacks DB. Controversies around the measurement of blood ketones to diagnose and manage diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes Care 2022;45:267-72

- Kilpatrick ES, Butler AE, Atkin SL, Sacks DB. Establishing pragmatic analytical performance specifications for blood beta-hydroxybutyrate testing. Clin Chem 2023;69:519-24