Facing the tragedy of a child’s death has profound effects both on families and their medical teams. In the midst of their grief, many families ask questions about why their child died. They yearn for the name of a disease or anatomic findings to which that they can direct their feelings of anger and pain. Knowing the “why” helps bereaved families understand what happened to their child and enables them to begin framing both their past and their potential future family planning.

Unfortunately, answers are not easy to offer. While autopsy is immensely helpful in discerning the cause of death, there are times when the family may decline autopsy—or the findings are inconclusive—and further testing is warranted.

Genetic testing during the perimortem period (at or before the time of death) sometimes can offer critical resolution to these etiologic questions. But it poses a number of unique challenges for laboratorians and clinicians, including: discussing potential cause of death and need for further testing with the bereaved family, determining which tests to order, ensuring appropriate specimen collection and integrity, adhering to the goals of laboratory stewardship committees to reduce unnecessary laboratory testing, and determining a payer source when insurers deny coverage. Moreover, families and clinical care teams often have to make rapid decisions under emotionally strained circumstances.

At Kentucky Children’s Hospital, we developed an innovative, transdisciplinary approach to the perimortem genetic testing process. We created a philanthropic fund to help offset the cost of testing for families and established family meetings to discuss the results and plan future steps.

A Family’s Journey Inspires Action

We were inspired to create a process for perimortem testing at our institution—by one poignant clinical case in which the parents were shocked to learn that their pregnancy was imperiled when an ultrasound revealed significant arthrogryposis (joint abnormalities) and severe skeletal anomalies. Their daughter was born with severe respiratory failure that did not improve with maximal medical support, and she died a few days after birth.

Specimens were obtained to perform genetic testing; however, because of her death, their insurance denied coverage of any testing due to the “testing not impacting her current medical care.” Clinicians made many attempts to appeal or find other funding sources without success.

In the meantime, the parents became pregnant again, and the fetus again showed signs of arthrogryposis. This news was devastating for the parents, and they had many questions about how this could happen to them again. This case underscored the importance of finding the “why” to a child’s death, both to help the family cope and to provide more information for family planning strategies if desired.

Stakeholders across the institution—from pathologists, laboratory scientists, and clinical chemists to geneticists, pediatric palliative care specialists, hospital administrators, business partners, philanthropists, and legal/compliance professionals—assembled to tackle this problem as a process-improvement project. The overall project was broken into steps: Create a policy and process for perimortem genetic testing; ensure specimen integrity and handling; create a philanthropic fund and approval committee; and develop a review committee to oversee the process and approval of testing. We set a goal to offer genetic testing to at least 90% of bereaved families that met criteria when indicated using our new process.

The project took about a year and a half of work from the perimortem genetic testing committee, and refinement to the process is ongoing. The initial policy work emphasized the balance of patient-centered care with fiscal responsibility, similar to any other laboratory stewardship program. The committee wanted to ensure a transparent process with well-defined inclusion criteria for genetic testing in the inpatient setting that was also agile enough to respond rapidly to the clinical demands of life-threatening cases.

Honest communication among this interdisciplinary team proved essential. Our committee was successful in openly discussing the tension between clinical indications for testing and the financial burden to families or the institution if insurance coverage is denied. The committee looked for sustainable solutions to ensure patient- and family-centered care for bereaved families. The formation of a philanthropic fund became a viable avenue to shoulder the burden of cost for under resourced families in need of answers.

Developing a Philanthropic Fund

Insurance plans largely do not cover perimortem genetic testing for the purpose of family planning or developing future reproductive strategies. As a result, some families may be put in financial jeopardy because they have to pay many thousands of dollars out of pocket for testing that isn't covered by insurance. Our team worked to create a process to approve and allocate funds to pay for genetic testing to find answers, inform family planning, and avoid putting families through financial hardship.

Our team was inspired to create a philanthropic fund after taking care of the Embry family (who graciously gave me permission to share their story). Jill and Brandon Embry were excited to find out they were having a girl during their second pregnancy and named her Claire. Prenatal genetic testing, however, revealed that Claire had CHARGE syndrome (Coloboma of the eye, Heart defects, Atresia of choanae, Retardation of Growth and development, and Ear abnormalities). While this news was devastating for the Embrys, they used the genetic testing information to help create a birth plan that ensured Claire’s comfort and bonding with both her parents and brother before she passed away.

The Embrys wanted to find purpose through the grief of losing Claire by raising money for genetic testing for other families. Our team was able to add the funds the Embrys raised to existing funds given by a pathologist named Dr. Golden, establishing the Golden-Embry fund. Funding is usually the rate-limiting step for philanthropic development, so with this step solidified, our team our team focused next on developing a solid process for ensuring that funds were approved and allocated in a just and equitable manner. Creating this funding allocation policy and referral guideline was a multistep process with stakeholders including laboratory scientists, pathologists, geneticists, genetic counselors, the palliative care team, hospital administrators, the legal team, and philanthropy officers.

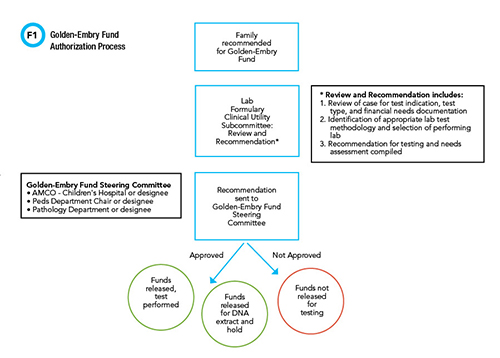

Figure 1 shows the authorization process for using funds for genetic testing. Initial referrals to the Golden-Embry fund come from two primary teams—genetics and palliative care. The primary social worker assesses and documents financial need. The laboratory formulary clinical utility subcommittee reviews the case for testing indication and testing type and ensures financial need is documented. A recommendation from the lab formulary utility subcommittee then goes to the Golden-Embry fund steering committee for final approval.

See Figure 1 in CLN May PDF

The fund steering committee includes the chairs of pediatrics and pathology and the associate chief medical officer for the children's hospital. The steering committee may decide to approve the total amount for testing up to the maximum per patient, allocate funds for DNA extract and hold, or deny the request. In the 2 years since the funding process was established, 22 bereaved families have had the opportunity for genetic testing with this mechanism, and the authorization process has usually taken no more than 2 days. No cases have been denied funding to date. Several cases have revealed a direct etiology that explained the child's cause of death, and for many of the families, genetic testing has been able to rule out inherited diseases and inform family planning strategies.

Transdisciplinary Review Committee

The collaborative and transdisciplinary character of the perimortem genetic testing committee has been a key to its success. At the beginning of this project, we discovered a lack of coordination among different departments in the hospital and no unifying process or protocol. We learned that establishing communication channels was just as important as creating policies and a process for testing. Many of the frontline clinicians discovered the complexity of billing in the postmortem period, and the laboratory scientists and pathologists discovered the difficulty of obtaining specimens at the bedside. Learning from each other helped us comprehend the full scope of the process and work together to create a solution.

The ongoing collaboration among all of these stakeholders who initially gathered to address perimortem genetic testing became the foundation for the hospital’s creation of the lab formulary clinical utility review subcommittee in Figure 1. This committee reviews pediatric perimortem genetic testing and meets regularly to refine the process. The subcommittee set up a shared database of cases to speed asynchronous communication and avoid duplication. This subcommittee reports to the hospital-wide lab formulary clinical utility committee that reviews all genetic testing cases above a certain dollar threshold and manages lab stewardship across the health system.

This review subcommittee has been key in the sustained effort required to ensure continued forward movement of each case through the process. And the transdisciplinary meetings have sparked new initiatives and quality-improvement projects, including initiatives to ensure specimen collection and integrity.

For example, to close the gap between bedside clinicians and laboratory professionals, our perimortem genetic testing subcommittee identified barriers to specimen collection including availability of appropriate media, collection tubes, and requisition forms. Pathology developed a streamlined protocol for on-call pathologists to help bedside clinicians obtain and store specimens. These refinements have successfully changed the workflow for specimen collection and storage for perimortem genetic testing, and also improved relationships between the laboratory professionals and pathologists with bedside clinicians.

The Laboratory’s Role in Bereaved Family Meetings

A crucial part of testing pathways and funding protocols is the follow-up with families after testing is completed. The participation and insights from laboratory medicine professionals are critical to ensuring these discussions meet the family’s needs.

Family meetings have a dual purpose: They provide families space to reprocess the events of their child’s death and an opportunity to talk about completed testing or autopsy reports. Sometimes, families ask questions that may have surfaced weeks or months after the death.

The meetings can also help resolve guilt and blame, which can be common among bereaved families. Reassurance from a trusted provider can be beneficial for many families. Feelings of guilt and blame are a common theme among bereaved families, and it can be liberating to hear from a trusted provider about their role in their child’s care. Such questions also give the healthcare team an opportunity to review all the ways that the parents advocated and cared for their child. Some families want to know all of the details of the testing and autopsy, so we come prepared to show pictures or review scans.

Other families request a more high-level review of the information, with emphasis on the meaning behind the results and their future implications. We recommend asking families what kind of information they would like and how they prefer to review it. This respects their boundaries and can avoid further traumatization.

We have used multiple modalities for family meetings including in-person, video conferences, and over the phone, depending on family preference. If an in-person conference is preferred, our team has made parking vouchers, water, and tissues available for family members. In the past two years, we have offered meetings to 18 families, and 14 have accepted. All of the meetings have been well received, and the families have expressed gratitude for the ability to discuss their child with the team.

The professionals present for a family meeting vary based on each case and requests from the family, but could include representatives from the primary medical team, subspecialists, bedside nurses, pathologists, geneticists, genetic counselors, chaplains, social workers, the palliative care team, and child life specialists. We designate one person as the facilitator, and he or she introduces all the people present and manages the meeting.

The Need for Better Coverage from Insurers

While we are proud of the progress of our testing process, we hope that insurers will extend coverage of perimortem genetic testing so we will no longer need to rely on philanthropy to cover these tests. Insurance companies could in the future take a broader view of families’ health, and offer coverage of genetic testing for family planning strategies, cause of death, and recurrence risk.

The downstream health implications for bereaved families are significant, and establishing a cause of death can be critical in preventing complicated grief and minimizing mental and physical health effects of enduring trauma. In the meantime, we will continue to rely on our transdisciplinary team to help bereaved families find answers in the midst of a tragedy.

We would like to thank Dr. Golden and his family, and Brandon and Jill Embry, for their generous donations and their commitment to the well-being and health of families who have a child with serious illness. We also appreciate the commitment of the members of our transdisciplinary team, who works tirelessly to ensure bereaved families can seek answers.

Lindsay Ragsdale, MD, FAAP, FAAHPM, is an associate professor of pediatrics and chief of the division of pediatric palliative care at Kentucky Children’s Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. +Email: [email protected]

Suggested Reading

- Lahrouchi N, Raju H, Lodder EM, et al. The yield of postmortem genetic testing in sudden death cases with structural findings at autopsy. Eur J Hum Genet 2020;28:17-22.

- Toufaily MH, Westgate MN, Lin AE, et al. Causes of congenital malformations. Birth Defects Res 2018;110:87-91.

- Vissers L, van Nimwegen KJM, Schieving JH, et al. A clinical utility study of exome sequencing versus conventional genetic testing in pediatric neurology. Genet Med 2017;19:1055-63.

- Neubauer J, Lecca MR, Russo G. Post-mortem whole-exome analysis in a large sudden infant death syndrome cohort with a focus on cardiovascular and metabolic genetic diseases. Eur J Hum Genet 2017;25:404-9.

- Kutscher EJ, Joshi SM, Patel AD. Barriers to genetic testing for pediatric medicaid beneficiaries with epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol 2017;73:28-35.

- Filges I, Friedman JM. Exome sequencing for gene discovery in lethal fetal disorders--harnessing the value of extreme phenotypes. Prenat Diagn 2015;35:1005-9.

- Scheimberg I. The genetic autopsy. Curr Opin Pediatr 2013;25:659-65.

- Kauferstein S, Kiehne N, Jenewein T, et al. Genetic analysis of sudden unexplained death: A multidisciplinary approach. Forensic Sci Int 2013;229:122-7.

- Krier JB, Kalia SS, Green RC. Genomic sequencing in clinical practice: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2016;18:299-312.