Amid COVID-19 restrictions, data show that health screenings have plummeted. Cervical cancer screenings in particular have dropped, portending worse outcomes for at-risk women. Self-sampling kits—the predominant method of cervical cancer screening in some countries—are undergoing clinical trials in the U.S., which could help bridge this gap in areas that do not quickly bounce back from pandemic restrictions. At the same time, sliding guidelines on cervical cancer screenings, and debates about which kind of test is best are are muddying the waters for patients and clinicians about the best way forward.

In light of all this, experts say that clinical laboratorians must prepare to advise health systems and clinicians not only on test selection and interpretation, but also how various screening efforts should restart—or even escalate—as the pandemic’s effect on routine screenings and healthcare visits wanes.

Screening Works—When It Happens

Expanding access to cervical cancer screening is critical. About 14,000 new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed in the U.S. each year, according to the National Institutes of Health, and more than 4,000 Americans die of the cancer every year.

Screening has proven its value and reduced the incidence of cervical cancer deaths by more than 60% since it was introduced in the 1950s. However, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, a Mayo Clinic study found that less than two-thirds of women were up to date on their cervical cancer screenings (J Womens Health 2019;28:244-9). Among those age 21–29, just over half were current.

Lead author of the study Kathy MacLaughlin, MD, wrote that these results should encourage healthcare providers to look for new ways to reach patients for screenings. The study encourages testing clinics to offer evening and Saturday hours, and urgent care clinics to offer cervical cancer screenings. Another option not addressed in this study: at-home testing kits.

Data Reveal How Shutdowns Lead to Skipped Screenings

The COVID-19 pandemic greatly exacerbated screening problems. As hospitals shifted their focus to treating COVID-19, patients with less-serious conditions steered away from medical centers. In some cases, physicians were forced to postpone nonemergency care. For these and other reasons, women skipped regular cervical cancer screenings along with other preventive care.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a group of approximately 1.5 million women in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California network, cervical cancer screening rates dropped about 80% during California’s first stay-at-home order from March 19, 2020 to June 11, 2020 (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:109–113). Screening rates were 78% lower among women ages 21–29 and 82% lower among women ages 30–65. The decrease was similar across all racial and ethnic groups. The silver lining—rates returned to near normal after reopening.

The results weren’t shocking, according to Chun Chao, PhD, cancer epidemiologist at Kaiser Permanente Southern California, and she was encouraged when rates returned to baseline so quickly after the lockdown. “That’s good but a little surprising,” she said.

The results also point to where at-home testing kits could help women stay on target. “At Kaiser, we screen for colorectal cancer this way. They take a sample and mail it back. That has continued during the pandemic and even after the stay-at-home order,” said Chao. “At-home self-collection could play a very important role if, God forbid, we’re in a similar situation again.”

Can Home Testing Bridge The Gap?

There are no Food and Drug Administration-approved at-home screening kits for cervical cancer, but they are in the works, as are clinical trials. Later in 2021, the National Cancer Institute plans to launch a multisite trial of about 5,000 women to see whether self-testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) is comparable to going into a physician’s office. This effort goes beyond how to screen during a pandemic and toward tackling how difficult it is for many women to navigate the U.S. healthcare system.

“A lot of women who most need to be screened don’t have those resources, so who knows when they’re going to come in,” said Anna Giuliano, PhD, founding director of the Center of Immunization and Infection Research in Cancer at the Moffitt Cancer Center. At-home screening has its limits, though. “If they test positive for a cancer-causing HPV-type, they will have to come to a health center for further diagnoses and treatment,” she added.

Healthcare systems would also need to set up the infrastructure to mail, collect, and perform those tests, and have a process in place for suspected positives, Chao noted. “The first priority is to look at those women who normally don’t come in. Can you get them to send their samples back with this new approach?” she said.

This isn’t a radical idea either. Self-collection kits are already the primary method of screening in New Zealand, Australia, and Europe, and they're the recommended method of screening by the World Health Organization.

In a recent review of the literature around cervical cancer and other screening programs, researchers from the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, emphasized that healthcare professionals should consider the many disruptions caused by the pandemic as an opportunity to improve screening programs (JCO Global Oncology 2021;7:416-24).

“In these unprecedented times, reassessing a cancer screening program could be an opportunity of building back better services,” the authors wrote. “Performing a situation analysis and planning accordingly, prioritizing, and keeping focus on evidence-based practices, considering implementation of evidence-based innovations (telehealth and new algorithms), and considering deimplementation of nonevidence-based practices.”

Guidelines On Screening Keep Changing

Beyond the hurdle of improving access to screening for patients, recent changes in testing recommendations have created confusion about the best way to screen in general. In July of 2020, the American Cancer Society (ACS) updated its guidelines for cervical cancer screenings in several ways.

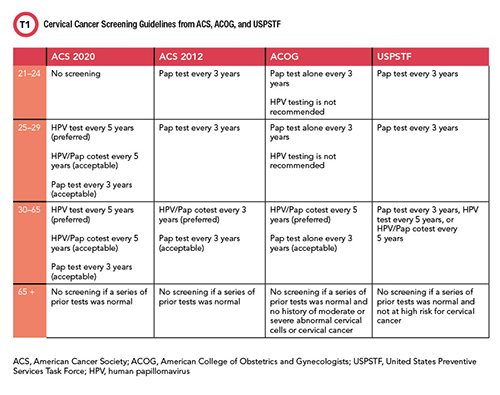

One of the most significant changes in the ACS guidelines is a preference for HPV testing alone instead of cotesting, which pairs a Pap test with an HPV test. ACS also recommended that anyone with a cervix start screening at age 25 instead of 21, and that those ages 25–29 be tested every 5 years with an HPV test instead of every 3 years with a Pap test. For those ages 30–65, the recommendation is now an HPV or cotest test every 5 years or Pap test every 3 years, where before the recommendation had been a cotest or Pap test every 3 years. These new recommendations still differ from those of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (See Table 1).

See Table 1 in CLN May PDF

Nicolas Wentzensen, MD, PhD, senior investigator at the National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Epidemiology & Genetics said in a National Institutes of Health blog post that all three tests can find warning signs of cervical cancer, and that HPV tests are more reliable and accurate than Pap tests. Pap tests also detect abnormal cells that have nothing to do with HPV, which can create false positives, he emphasized. Those in turn can result in inappropriate treatments, which typically involve removing tissue from the vagina and cervix, and can “permanently alter the cervix. That may raise the risk of serious complications in future pregnancy including pregnancy loss and pre-term birth,” he said.

However, not everyone in laboratory medicine is on board with the new screening recommendations. A recent study from Quest Diagnostics and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center found that the HPV and Pap tests done alone are less likely to detect cervical cancer and precancer than using together in a cotesting scheme (Am J Clin Pathol October 2020;154:510-516).

The study assessed the sensitivity of an HPV test alone, Pap test alone, and cotesting in nearly 19 million cotest results performed by Quest Diagnostics between 2010 and 2018. Of 1,615 cotests taken at any time prior to cancer diagnosis, 86.90% were positive by cotesting with a false negative rate of about 13%. By comparison, false negative rates in Pap tests and HPV testing alone were nearly twice as high: 26.4% for the Pap test and 28.4% for the HPV test.

Researchers also found that cotesting detected significantly more women who developed biopsy-confirmed adenocarcinomas, a particularly aggressive form of cervical cancer. Cotests identified 82.3% of this cancer compared to 61.2% by HPV and 59.7% by Pap.

“The bottom line is that cotesting is better than either test alone,” said Harvey Kaufman, MD, senior medical director at Quest Diagnostics. “It’s not really a comparison of Pap or HPV, it’s that with either test versus cotesting, cotesting wins.”

That doesn’t bode well for the efficacy of at-home kits based on HPV detection. Plus, Kaufman said, an annual exam isn’t just a test. “The doctor is doing more than collecting a specimen,” he said. The clinician takes a patient’s history and performs a physical exam, which is also why he doesn’t think virtual visits will replace regular care. “They’re trained to look for anomalies and you can’t do that remotely,” he said.

Kaufman said that despite being critical of some of the ACS changes in the guidelines, he realizes that laboratory professionals have no control over how they were developed. “The best a laboratorian can do is carefully review the literature to guide decision-making,” he said.

Jen A. Miller is a freelance journalist who lives in Audubon, New Jersey. @byJenAMiller