A recent report from the American Cancer Society (ACS) points to worrisome trends in prostate cancer (CA Cancer J Clin 2023; doi: 10.3322/caac.21763). After 2 decades of decline, the incidence of prostate cancer increased by 3% annually from 2014 through 2019, translating to an additional 99,000 new cases. About half of these were advanced cancers. Experts say prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing trends contributed to these changes in prostate cancer statistics.

The current uptick was driven by increases of about 4.5% annually for regional-stage and distant-stage diagnoses that began as early as 2011. Localized-stage disease also has begun to tick up, although the trend is not yet statistically significant.

These results are “very concerning,” said lead study author Rebecca Siegel, MPH, senior scientific director of surveillance research for ACS. Long-term prostate cancer incidence trends “are quite erratic, much more so than any other cancer,” she said. Cases spiked in the early 1990s because of widespread uptake of PSA testing among previously unscreened men.

More recently, reported prostate cancer rates have been declining, by about 40% since 2007, Siegel said. This was thought to reflect changes in the recommendation for PSA testing by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). USPSTF recommended against PSA screening in men 75 and older in 2008, and in 2012 against any PSA screening at all, in part following results of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, which found no difference in prostate cancer mortality rates among men who had or had not undergone PSA screening (N Engl J Med 2009; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810696). However, it was later noted that some 80% of men in the no-screening group actually had undergone at least one PSA test, calling the findings into question (N Engl J Med 2016; doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1515131).

In 2018, USPSTF revised its recommendation, stating that men ages 55−69 should make individual decisions about whether to undergo PSA screening for prostate cancer based on discussions with their clinicians about screening benefits and harms (JAMA 2018; doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710).

But Siegel and others say the damage from the earlier recommendations may have been done.

“We’ve had a lot of progress against prostate cancer, so there’s a concern that this is a reversal in that progress,” she said. “Mortality rates are still declining very slowly, but it looks like they’re starting to stabilize. And we have this increase in advanced-stage diagnoses, which are not nearly as easy to treat, and outcomes are not as good.”

It may take several years to see prostate cancer rates fall once again, especially factoring in the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its disruptions to preventive healthcare, said Douglas Scherr, MD, chief of the division of urologic oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine-NY Presbyterian Hospital, in New York City.

“We used to see a lot of low-risk prostate cancer,” he said. “Now, on the contrary, we’re seeing a lot of very high-risk prostate cancer in younger individuals and all age groups. It’s a paradigm change.”

Any increase or decrease in detection is a result of PSA screening and potentially newer techniques to identify prostate cancers, added Jonathan Epstein, MD, the Reinhard Professor of urologic pathology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. There are some differences among the guidelines, he said, which contributes to the controversy.

The USPSTF guidelines are aimed at general practitioners, he said, while the American Urological Association advocates that clinicians discuss PSA screening with patients ages 45−75. ACS recommends that men starting at age 50 make an informed decision on whether to be screened following a conversation with their healthcare provider, Siegel said. Black men should begin this conversation earlier, at age 45.

Additionally, multiparametric 3T MRI is now picking up some cancers that previously would not have been detected, potentially leading to an increased incidence. “But it’s also doing a better job in detecting the more aggressive components of the cancer, and not finding as much the lower-grade, like indolent cancers that you potentially don’t want to find,” Epstein said.

PSA IS STILL A GOOD STARTING POINT

PSA still is considered the gold standard as a start to prostate cancer diagnosis, Scherr said. However, he noted, urologists have gotten smarter about how best to utilize the test. A quarter of patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancers can be put on active surveillance versus treatment, thanks to technologies such as multiparametric MRI, which provides clinicians detailed prostate views of those who have an elevated PSA to determine if biopsies are needed, and if so, what area of the prostate to sample.

Additional tests are aimed at improving the specificity of PSA. These include PSA density, which is PSA divided by prostate volume measured by ultrasound; free PSA, the amount of PSA free floating unbound to other proteins; and the prostate health index (PHI), a PSA-related blood test to help determine the probability of detecting prostate cancer with a biopsy. Another blood test, 4K, measures four PSA-related proteins to assess prostate cancer risk.

“There’s a lot now on the market,” he said. “Some of it’s valuable, some of it’s not terribly useful, but all in all, it has definitely improved PSA validity.”

Commercially available urine tests also include PCA3, which can help identify genetic markers and elevated PSA, ExoDx Prostate

and SelectMDx, for men with elevated PSAs of between 2 and 10 ng/mL—the so-called “gray zone” where urologists may not be sure whether to biopsy or not, said Christian Pavlovich, MD, the Bernard L. Schwartz Distinguished Professor in urologic oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“There are tests like these that could be run in a reflex manner,” Pavlovich said. For example, when a PSA test comes back in the 4-10 ng/mL range, or 2.5-10 ng/mL range, labs can reflexively run a PHI or other related test using the same blood sample. As a follow-on to those results, labs could be set up to receive or run urine samples on the same patients to study markers of prostate cancer.

“We’re looking for markers of aggressive or more advanced disease," he said. “PSA is only going to suggest there’s something wrong in the prostate, whether it’s inflammation, benign growth, cancer, or infection. That’s where imaging, advanced biomarkers in the serum, and urine are playing their role.”

So-called “super sensitive assays” that identify very low levels of PSA, such as in patients who have had a prostatectomy, also are important, Scherr said. PSA velocity, the rate of change of PSA over time, is helpful to determine when a patient may have a local recurrence or micrometastatic disease—small collections of tumor cells that spread to another part of the body.

These other tests vary in popularity among urologists, who may ask labs to stock the tests they’re most interested in, Epstein said. “It’s not like one [test] is definitively recommended over the others. They’re all kind of competing against each other.” The National Comprehensive Cancer Network puts out an annual guideline on prostate cancer that reviews tests that are adjuncts to PSA, and is a good resource, he said.

GENOMIC BIOMARKER TESTS ON THE HORIZON

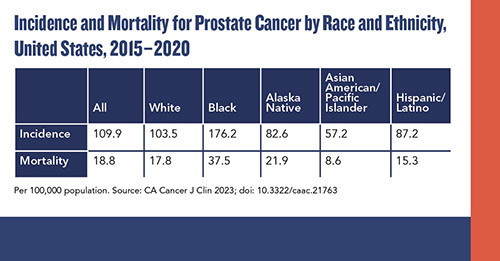

A growing area in the field is the evolution of genomic biomarker tests for prostate cancers, said Scherr and Pavlovich. The ACS report emphasizes this specifically for Black men, for whom racial disparity is particularly significant in prostate cancer. “Black men benefit more from screening in general, and from the integration of personalized biomarkers because they are more likely to harbor genomically aggressive cancer, even with clinically low-risk disease,” the authors noted. Prostate cancer incidence is 70% higher in Black men than in White men.

“If someone is diagnosed with prostate cancer, we can evaluate the mutational load of those cancers, and it enables us to place patients into a low-, intermediate-, or high-risk category as to whether their prostate cancer needs to be treated or not,” Scherr said.

Commercially available tests include Decipher, Oncotype DX, and Prolaris.

“We’re not quite ready to say, ‘Get a blood test to look for your genetic predisposition,’ because we don’t know enough about that to say that some people, based on that, don’t need to worry about cancer and others do,” Pavlovich said. “But once cancer is diagnosed, genomic tests can look at the aggressiveness of the cancer itself beyond what our pathologists look at visually and with their special stains.”

Screening itself also could continue to change.

“There’s a lot of effort going on to try to optimize screening, and I have a feeling there are some changes coming soon so that men can be tested, and we can act on cancers that actually may prove to be fatal, versus treating everything that comes up in terms of a moderate PSA level,” Siegel said. “There’s definitely hope on the horizon, but right now we’re in a bit of a difficult place.”

Karen Blum is a freelance medical and science writer who lives in Owings Mills, Maryland. +Email: [email protected]