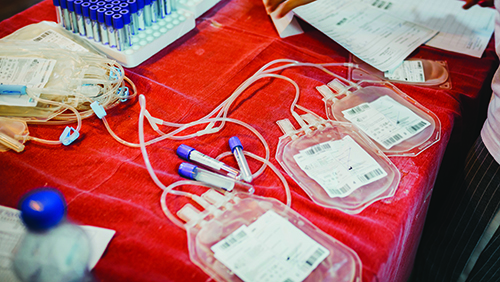

Times are tough for blood banks and clinical laboratories working with blood products. In January, the American Red Cross announced it was facing its worst blood shortage in over a decade. The organization cited “relentless challenges” due to the COVID-19 pandemic, including a 10% overall decline in the number of people donating blood, as well as ongoing blood drive cancellations and staffing limitations. The pandemic contributed to a 62% drop in blood drives at schools and colleges.

Clinical laboratories and the transfusion medicine community say they are feeling the pinch.

“We lost 10–15 percent of our blood donor pool” from people working at home and corporations not holding their typical regular blood drives, said Magali Fontaine, MD, PhD, director of the transfusion service at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore and a professor of pathology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. What’s more concerning, she said, is “the shortage that we have currently is probably here to stay because of the circumstances around how it impacted blood donor and donation practices.”

Additionally, there has been a shortage of phlebotomists, in part because of the Great Resignation, Fontaine noted. The good news, she said, is there are signs the situation could slowly be getting better as businesses reopen and blood suppliers work hard to “revise and use technology to access donors, particularly social media.”

Creative Solutions to an Unprecedented Challenge

With a Level 1 trauma center as well as busy organ transplant and cancer programs, Fontaine’s medical center easily goes through 50–150 units of blood per day, and transfuses 60,000 products a year. “Our constant worry is that one of those patients depletes us in no time,” she said. “So we constantly have to look out for the remaining patients in the hospital, or trauma patients that have not yet been admitted.”

Fontaine and colleagues take all precautionary measures to preserve their supply of blood and blood products. They scrupulously enforce their transfusion guideline. If a transfusion is ordered outside the guideline, the laboratory intervenes and double-checks that the indication is relevant, Fontaine said. They also rigorously maintain a 5-day supply of blood; any time it starts to drop, they begin discussions with department chairs of critical care areas to monitor patients more closely, perhaps putting off some operations or using blood salvage techniques until inventory recovers. And, they ensure no products expire by taking in units from smaller sister hospitals in the health system before they are wasted.

The University of Maryland is not alone.

“This is simply unprecedented,” said Aaron Shmookler, MD, an assistant professor of pathology, anatomy, and laboratory medicine at West Virginia University (WVU) in Morgantown.

WVU’s Ruby Memorial Hospital is serviced by three blood suppliers. Just before the pandemic, Shmookler and colleagues established a means of transferring blood products among their health system hospitals using a courier service. This was designed both to save money and to ensure units wouldn’t expire without being used. But it has proven prescient: Shmookler recently received a call about a patient at a sister hospital who was hemorrhaging, in fast need of blood. He was fortunate to be able to send units immediately to help.

His laboratory is employing other practices as well. Using tips from the Association for the Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies to extend the blood supply, they developed crisis standards of care for the use of blood products at their hospital and shared it throughout their 16-hospital network for others to adapt as they chose. This includes measures like providing O-positive red cells for emergent transfusion to males or females who are no longer of child-bearing age (conventional level), and considering no prophylactic use of platelets (crisis level). “That’s a means of ensuring that we are conserving the blood supply as much as possible and transfusing patients who absolutely need blood,” Shmookler said.

Additionally, his group closely monitoring inventory each day, maintaining open communication with hospital leadership and other centers, working with blood suppliers, and thinking of alternative strategies for transfusion patients that are not inclusive of blood. “If you have severe trauma cases, we can give other medications such as prothrombin complex concentrate, or recombinant factor VII,” he said.

At George Washington University (GW) Hospital in Washington, D.C., Xiomara Fernandez, MD, calls on skills she learned when she trained in Hawaii, where time and distance from neighboring islands and the mainland United States forces clinical laboratories to be self-sufficient.

Like at the other centers, her lab is strict about enforcing hemoglobin transfusion thresholds, putting an alert in their electronic health record ordering system. If a provider still orders products, the order has to be approved by the blood bank resident or attending physician. Education of clinicians is key, said Fernandez, medical director of transfusion medicine and coagulation, and an assistant professor of pathology at GW School of Medicine & Health Sciences. Her hematology department also has been helpful in guiding primary providers about when to transfuse.

The blood bank reviews all orders for platelets and plasma, she said. And, because providers tend to order blood products “just in case” for procedures, blood bank staff confirm those procedures are moving ahead so product isn’t wasted. But there are still surprises. Fernandez said this is the first time she has experienced a shortage in cryoprecipitate, due in part to a shortage of staff to prepare the products. She and her colleagues push thromboelastography tests to guide transfusion or determine if cryoprecipitate is necessary.

On the plus side, news coverage of the shortages means that physicians and nurses are more aware of the situation and less likely to become upset with the blood bank, Fernandez noted. “They realize it’s happening everywhere, and it’s not something the blood bank or the lab or the hospitals are doing,” she said. It has also encouraged smaller hospitals that may not have had patient blood management programs in place to start, she said.

From Blood Products to Blood Tubes

Over-testing has always been a concern among clinical laboratories worldwide, but it’s become a “particular concern” now with the shortage of blood tubes likely to last throughout the year, said Neil Harris, MD, director of the core (chemistry/hematology) laboratory at the University of Florida (UF) and a clinical professor at the UF College of Medicine’s Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Laboratory Medicine.

During the pandemic, healthcare institutions have experienced a shortage of blue-top vacuum tubes for blood sample collection because of high use of these tubes for coagulation tests and limited supplies to manufacture more tubes. Other types of tubes followed suit.

The Food and Drug Administration in January 2022 updated their device shortage list to include all blood specimen collection tubes (product codes GIM and JKA), and recommended that laboratory directors and other healthcare personnel consider conservation strategies to minimize blood collection tube use. Their tips include only performing blood draws considered medically necessary, reducing tests at routine wellness visits, and considering point-of-care testing that does not require collection tubes.

Fortunately, Harris said, “We’re not at the stage where we would refuse any tests.” But laboratorians can be more specific in providing guidance about testing, recommending that it fits with a patient’s history. Clinicians could use prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, platelet count, and fibrinogen. Some specialized testing, such as assays that detect propensity to venous or arterial thrombosis, should be done on an outpatient basis after a patient has been discharged, as results could appear positive in the presence of acute inflammation.

Harris and UF colleagues William Winter, MD, DABCC, FADLM, FCAP, and Maximo J. Marin, MD, wrote a paper to provide guidelines about laboratory ordering practices in coagulation testing. It’s in press at Laboratory Medicine.

“A considerable portion of laboratory testing is thought to be, for lack of a better term, nonproductive,” said Winter, a professor of pathology and pediatrics, and medical director of clinical laboratory support services and of point-of-care testing. “We wanted to emphasize to the laboratory community that through better ordering practices, we could reduce the cost of laboratory testing, we could potentially improve laboratory testing because it would be more guided, and as a side effect—at least in the short run—we could reduce tube utilization.”

The article provides a range of suggestions, such as asking for fewer standing orders, combining orders to reduce tube utilization, and using syringes in place of discard tubes when setting up infusions or peripherally inserted central catheter lines.

“There are a lot of creative ways to reduce test and tube utilization without having an adverse effect on patient outcomes that laboratories and clinicians should think of,” Winter said.

AACC is hosting a conference on June 3–4 in Alexandria, Virginia, on the role of the laboratory in reducing errors and improving quality in the preanalytical phase. It will cover test ordering, said Winter, one of the presenters. For more information or to register, visit www.myadlm.org/meetings-and-events

Karen Blum is a freelance medical and science writer who lives in Owings Mills, Maryland. +Email: [email protected]