Imagine for a moment that it is time to prepare your laboratory for its next regulatory inspection. Once the appropriate regulations, checklist, and standards or guidelines are in hand, what comes next? This is when clinical laboratory professionals responsible for regulatory compliance begin their internal audits, gap analyses, and documentation of compliance.

How is compliance documented in your laboratory? Chances are your laboratory compiles an evidence binder, a notebook full of examples of how the lab has complied with each requirement.

But there is an innate problem with this approach. In my experience as a laboratory administrator and directing quality programs, labs commonly compile their evidence binders using the best examples of how they have met requirements. As an auditor, when presented with such a collection of a lab’s best work, I say, “How wonderful that you put that together. Now, would you please pull all records associated with this random accession number I chose from the test on your test menu associated with the highest level of patient safety risk for this randomly chosen date range?” The point being, we all want inspectors to see how great our lab can perform. For a number of reasons, however, labs should be focusing on those instances in which they might not perform as well as they would like. We need to move beyond the evidence binder.

Organizational Honesty for the Benefit of Our Patients

When we cherry-pick our best quality records—whether the most pristine temperature monitoring records or the most bulletproof validations—we are not taking full advantage of the inspection process. We are not embracing a spirit of continuous improvement.

Letting go of our attachment to an evidence binder requires an important shift in our thinking. This shift requires us to stop acting in a defensive manner, denying deficiencies presented at an inspection closeout meeting. What I am proposing requires forethought, honesty, vulnerability, and transparency. It requires us to become self-aware, truly embracing continuous quality improvement. It is human nature to avoid facing areas in which we may not excel. But we need to keep oriented to our true north—the real purpose of laboratory medicine: ensuring accurate, precise, and timely laboratory results that provide value for our patients.

Allow Systems to Speak for Themselves

The alternative to relying on an evidence binder is allowing a laboratory’s systems to speak for themselves. This means letting the inspection process flow organically instead of supplying hand-picked examples of your best work for each checklist item. Be cognizant of the urge to put up a façade for those areas in which you perceive your lab is lacking. Encourage the inspectors to randomly select records to review, and do not steer them toward your favorite staff member to interview. Avoid the temptation to take deficiencies personally and become offended or angered when they are identified.

Your organization will learn valuable lessons about the effectiveness of its quality program by resisting the natural tendency to control the inspection process. Inspectors are encouraged to assess not only the quality framework but, most importantly, the effectiveness of its deployment across the organization. In this way, well-designed but ineffectively deployed systems will surface. Records, documents, reagents, supplies, and other resources that are not as accessible as necessary will be identified. Training programs might turn out to be not as effective as anticipated.

Essentially, holes in your laboratory’s systems will be brought to light. New strategies will be needed. This approach to inspections requires a cultural shift toward becoming a learning organization and embracing deficiencies as opportunities for improvement.

Using Your Time Wisely

Compiling an evidence binder to deal with each requirement for an inspection is an incredibly time-consuming process. No sooner than an evidence binder is completed, it becomes an outdated record of the way things were at that point in time.

Rather than making a scrap book of your compliance evidence, spend your time preparing for inspections by designing compliance audits and enhancing your quality program. Showing the auditors how things really work in your lab saves time and demonstrates what the lab staff experience in their daily work.

This is not at all to say that you shouldn’t document how you comply. Compliance software solutions can be used for this purpose and can provide an integrated solution to many other QMS components such as competency assessment, training, equipment management, environmental monitoring and non-conforming event management. Likewise, an Excel spreadsheet with links to your policies, procedures, and records as well as notes about how you meet each requirement will help you assess your readiness as well as jog your memory on inspection day. This type of documentation is extremely helpful and can prove invaluable if the lab’s primary quality contact is unable to participate during the inspection.

Shifting to a Culture of Quality

In order to effectively foster a culture of quality and organizational honesty, labs must balance accountability and systems thinking. For example, if employees are afraid they will be punished or shamed for deficiencies, they will be more defensive and more apt to steer auditors away from problem areas. Under a systems thinking model, managers embrace deficiencies and non-conformity reporting as opportunities to provide increasingly better services and approach each resulting quality improvement initiative with enthusiasm and encouragement. Shame and blame are counterproductive. Managers must acknowledge their role in and take responsibility for system failures that have led to deficiencies. If staff know that managers will approach deficiencies as opportunities to learn and to improve the quality of service to patients, staff not only take pride in their work but also feel empowered to bring forward their ideas for continuous improvement.

Becoming a transparent organization takes bravery, but it’s also freeing. The goal of inspections shifts from avoiding “getting in trouble” and instead becomes reaping full benefit from the inspection process to improve the laboratory and its services.

Climbing the Quality Hierarchy

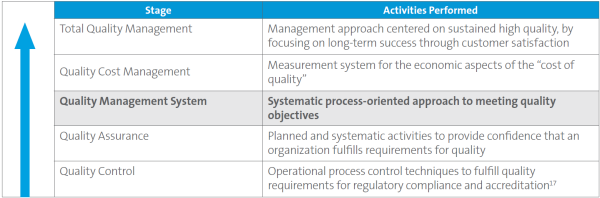

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) has summarized stages of quality in its Health Care Quality Hierarchy (Figure 1). Historically, clinical laboratorians have been very good at controlling quality in the analytical phase (2, 3), hence, quality control is the first stage in the quality hierarchy. However, focusing solely on analytical quality is not sufficient, as only 7%–13% of laboratory errors occur in this phase3.

Moving up the hierarchy, quality assurance is aimed at fulfilling regulatory requirements. This stage is what I call the “checklist mentality”—the philosophy that if there is a requirement, the lab will achieve and maintain compliance at a minimum level. Next, in the quality management system (QMS) level of the hierarchy, the lab formalizes a systematic, process-oriented approach to and framework for the quality programs to meet quality objectives (1).

Employing a systems thinking approach to inspections as described in this article can go a long way in helping a laboratory evolve to the spirit of the QMS stage and incorporate Total Quality Management (TQM) components. This approach will enable the laboratory to showcase its QMS while allowing identification of areas for improvement.

Conclusion

Clinical laboratories are evolving beyond just checking boxes on a checklist to meet quality assurance requirements. They are beginning to strive for best practices and foster a culture of continuous quality improvement in order to climb to the top of the quality hierarchy.

I challenge clinical laboratory managers and quality professionals to let their quality management systems speak for themselves on inspection day. Moving beyond the evidence binder is a powerful tool to help your laboratory in its quality journey. You will be surprised how much your lab will benefit. As an industry, we cannot settle for good enough. It is not enough just to pass. Our patients insist on the very best level of care and they deserve nothing less.

References

- CLSI. Quality Management System: A Model for Laboratory Services; Approved Guideline—Fourth Edition. CLSI document QMS01-A4. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2011.

- Goswami B, Singh B, Chawla R, Mallika V. Evaluation of errors in a clinical laboratory: a one year experience. Clin Chem Lab Med 2010;48:63-66.

- Plebani M. Errors in clinical laboratories or errors in laboratory medicine? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44:750–759.

Jennifer Dawson, MHA, DLM(ASCP)SLS, QIHC, is vice president of quality and regulatory affairs at Sonic Healthcare USA. +Email: [email protected]