Drive on highways in Philadelphia, and you’ll see typical billboards advertising products and services ranging from snack foods to health insurance, to personal injury attorneys. And then there’s a new, more jarring one: “DRUG RESISTANT GONORRHEA ALERT,” it cries in all capital letters, accompanied by an illustration of a boat hitting an iceberg, where most of the floating mass is below water.

The billboard from the AHF Wellness Center, which has locations across the U.S., is disturbing, but drug-resistant gonorrhea is one of a handful of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that are becoming more dangerous and common, experts say.

According to the CDC, more than 2.5 million cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis were reported in the U.S. in 2021, about 6% more than in 2020. Reported syphilis cases hit 176,000 in 2021, up from about 134,000 in 2020—as high as numbers have been since the 1950s. Congenital syphilis rose 32%, leading to 220 infant deaths and stillbirths.

The STI landscape is changing for many reasons, including reduced funding for STI testing that would catch cases before they spread, changes in behavior caused by the pandemic, and growing drug resistance from specific kinds of infections. Here’s what clinical laboratorians should look out for.

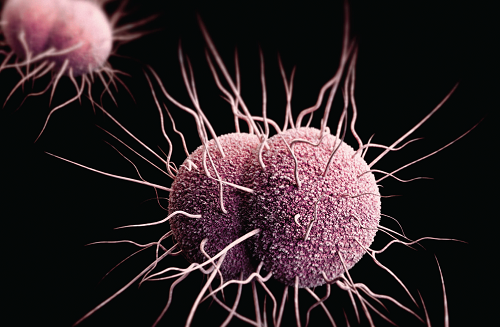

DRUG-RESISTANT GONORRHEA

Gonorrhea is the most commonly diagnosed STI, with 710,000 cases reported in 2021. That’s an increase of 4.6% from 2020, according to CDC. Cases have been rising over time, with the number of cases up 118% since 2009.

CDC estimates that half of gonorrhea infections show resistance to at least one antibiotic. And while that may sound alarminga—and look distressing on a billboard—it may not yet be as dire a situation as it seems, said Barbara Van Der Pol, PhD, MPH, professor of medicine and public health at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and president of the International Society for STD Research.

Resistance to one antibiotic does not mean the infection is untreatable. Only 0.2% of cases required four or more antimicrobials to treat, according to 2021 CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. And while a novel strain of drug-resistant gonorrhea was found in Massachusetts, that was only in two patients, and were both successfully treated with ceftriaxone, the current standard gonorrhea treatment, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Clinical laboratories are essential to identifying the right treatment to use first. “Many of those [with drug-resistant gonorrhea] could use older treatments if we had better diagnostic technology that would detect markers,” Van Der Pol said. “But we don’t know that, so we automatically go to the next-tier drug.”

With current technology, detecting drug-resistant gonorrhea would require testing from culture isolates, and eventually better molecular tools, noted Allison Eberly, PhD, assistant professor at the Washington University School of Medicine, and associate medical director microbiology and of the Molecular Infectious Disease Laboratory at the Barnes Jewish Hospital. “We have to try to culture the isolate, then at most labs it would be sent to a reference laboratory for antibiotic susceptibility testing,” Eberly said. “It can be performed at some places in-house. For us, the volume doesn’t warrant us bringing it in-house. It just takes time to get those results back.”

Furthermore, designing assays that would get FDA approval is not so easy. “If you want to develop a new test, you have to do a clinical study and are not allowed to use isolates out of a freezer,” Van Der Pol said. “How many people do you have to enroll to A, catch gonorrhea; B, catch drug resistant ones; and C, follow them up for clinical outcomes?” She doesn’t see a clinical diagnostic company willing to pay for such a trial. “That’s why we’re stuck.”

MYCOPLASMA GENITALIUM

Also on clinical laboratorians’ radars is Mycoplasma genitalium, which a 2022 study from the journal Sexually Transmitted Infections showed might be associated with an increased risk of pre-term birth (doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2021-055352). It can also lead to infertility in women. In men, it causes symptomatic and asymptomatic urethritis.

It’s still not considered a common STI, though: It’s been reported in 1.7% of people age 14–59 in the U.S, according to one report, with infection rates higher in people who have another STI (Sex Transm Dis 2021; doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001394).

Clinical laboratories can test for it. “It wouldn’t change much in terms of methodology or sample collection. Often the same specimens for chlamydia and gonorrhea can also be used,” Eberly said. “But what next?”

So far, research into what Mycoplasma genitalium does, especially in asymptomatic patients, isn’t mature enough to answer that question. “What happens with that test result? If clinicians aren’t certain what to do with a positive result, how do they know when to treat?” she said.

The CDC does not recommend screening for asymptomatic patients. Van Der Pol agrees, because doing so may lead to treatment and make Mycoplasma genitalium more drug resistant. “We don’t always want to treat it. We’re not sure if it has long-term downstream health outcomes, and asymptomatic infections may self-clear and then cause no problems,” she said. “It develops resistance so quickly, that if you try to treat it and don’t know the resistance profile you’re likely to lead to more resistance.”

POINT-OF-CARE TESTING ENTERS THE FRAY

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the accelerated development of all kinds of at-home testing. One lasting effect of that is the acceptance or even expectation of such tests from patients. “The pandemic really opened the doors to the possibility of self-collection,” said Eberly. “We need better access to all kinds of testing and a strategy to bring testing access to folks.”

She also doesn’t think home tests will entirely replace laboratory-based molecular testing, as molecular tests are often are used to confirm a point-of-care test diagnosis — as it was before COVID-19. Laboratories confirm many other home tests the same way.

In March, Visby Medical received FDA clearance and a CLIA waiver for their second-generation Sexual Health Test for Women point-of-care test, a PCR diagnostic test for chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis. The company reports that the tests have 97% accuracy, and that their device returns results in 30 minutes.

It’s a rare achievement in at-home testing kits for STIs, said Van Der Pol, because the FDA wants 95% accuracy, which can be difficult to achieve. She added that, in a lot of cases, “even 80% accuracy would be better than no test at all.”

Because the FDA barrier is so high, though, many direct-to-consumer tests (also called online tests and self-tests) offer only laboratory-developed tests and are marketed as a more convenient and less stigmatized option to STI testing. In a position statement, the American Sexually Transmitted Disease Association (ASTDA) acknowledged that these tests are appealing to some consumers because they can be initiated at home and allow people to avoid potential embarrassment or discomfort around a discussion of sexual history (Sex Transm Dis 2021; doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001475). They added that the tests also may reduce the burden on health care providers.

But the organization also cautioned about several problems within the home-testing landscape. At-home tests can be hard to access for those who are experiencing housing insecurity and therefore don’t have a fixed mailing address. The costs, which ASTDA found typically range from $49 to $189 or higher, may be prohibitive, and are often not reimbursable by insurance because they’re not ordered by a healthcare provider. Using these tests also requires internet access, which 8% Americans don’t have at home.

Another concern was that ASTDA found that bundled direct-to-consumer tests may include unnecessary assays, like for Ureaplasma species or Mycoplasma hominis, for which there are no screening or treatment recommendations. They also found that the methodology to determine validity of the collection, transport, and testing process is often not made public. The ASTDA recommends these laboratories offer follow-up care as well, which only some do.

Promises that these direct-to-consumer tests for STIs would usher in access to more people, and more kinds of people, have not yet panned out, said Van Der Pol. “We thought they would be really great in expanding access. But they can be expensive, and that’s not helping with health equity.”

As for billboards like the one in Philadelphia, she acknowledges that drug-resistant gonorrhea is a problem that is increasing worldwide. However, it’s a small sliver of the infectious disease picture, especially when the percentage of drug-resistant cases does not mean they are untreatable, she said.

Currently, only one treatment remains for resistant infections: cephalosporins. However, the CDC has not verified any clinical treatment failures using cephalosporin in the United States.

Jen A. Miller is a freelance journalist who lives in Audubon, New Jersey. Twitter: @byJenAMiller