Some 18,000 people in laboratory medicine will converge on Philadelphia from July 31 to August 4 for the 68th AACC Annual Scientific Meeting & Clinical Lab Expo to see the exposition, review the latest science, and connect with their colleagues from around the world. Of the meeting’s diverse and in-depth scientific content, the 2016 Annual Meeting Organizing Committee (AMOC) elected to highlight particularly the rapid changes occurring in treatment and testing for hepatitis C virus (HCV). This global threat affects some 3.5 million people in the U.S. and leads to chronic liver disease in 60–70% of cases. Powerful new drugs have given patients hope for a cure, but to optimally prescribe them, physicians rely on crucial information from laboratory medicine experts.

“We chose to invite this scientific track on HCV because it is a disease that impacts a large percentage of the population. While treatment is available—an expensive one—there is no vaccine, and it is not clear that current strategies will lead to eradication of the disease despite public perception otherwise,” said the 2016 AMOC chair, William Clarke, PhD, who also serves as director of clinical toxicology and associate professor of pathology at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore.

This special three-session scientific track on HCV begins Monday morning, August 1, with the 90-minute symposium, “HCV—Research in Treatment and Prevention.” Moderated by William Osburn, MS, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins, this session will offer an overview of current challenges in treatment, global health considerations, and research opportunities in HCV. Stuart Ray, MD, vice chair of medicine for data integrity and analytics and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins, will delve into state-of-the-art treatments, challenges, and opportunities based on his experience in treating patients and in performing HCV-related research. Joining Ray will be Justin Bailey, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins, who will explain the immune response against HCV and the latest developments in the quest to create a vaccine.

At mid-day on Monday, a second 90-minute symposium will take the form of a debate: “Is Hepatitis C of Continuing Concern, or Is It Going Away?” With Osburn moderating, Kimberly Page, PhD, MPH, division chief of epidemiology at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, will present the case that in the modern era of direct-acting antivirals (DAA), HCV is a vanishing problem. Camilla Graham, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School in Boston, will present a contrasting point of view.

Later on Monday afternoon Osburn will return as speaker and moderator for a 90-minute symposium, “HCV and Laboratory Medicine: Testing in Support of Screening and Diagnosis.” Joining him will be Arthur Kim, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the viral hepatitis clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Osburn will describe the “HCV diagnostic toolbox,” while Kim will cover the changing landscape of laboratory testing for HCV.

An Insidious Public Health Problem

HCV has no noticeable symptoms for years, but remains the number one cause of liver cancer and liver transplantation in the United States. As a result, even though new curative treatments are available, many patients are unaware that they are infected and so don’t seek out appropriate care. Although approximately 15–25% of those infected are able to clear the virus from their bodies without treatment and never develop a chronic infection, nearly 8 in 10 untreated people remain infected for life, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

As the growing burden of HCV became apparent to public health officials, a push for more HCV screening intensified in 2012 and 2013. First, in 2012 CDC updated its 1998 HCV screening guidance, adding baby boomers— adults born between 1945 and 1965—to its list of at risk groups who should be screened for HCV. On the heels of this change, the influential U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended in 2013 that all baby boomers be screened at least once for HCV. The recommendations were based on CDC data showing that three in four patients with chronic hepatitis C are baby boomers, and that many became infected before the virus was identified and the blood supply was tested for the disease.

Of course there are many other factors that should prompt providers to screen patients for HCV, according to the CDC guidelines. These include: illicit drug injection, even if only one time; conditions associated with HIV infection; hemodialysis; unexplained high aminotransferase levels; and blood transfusions and/or organ transplants prior to July 1992. In addition, children born to HCV-infected mothers, as well as healthcare, emergency medical, and public safety workers who may have been exposed to HCV-positive blood from a needle stick injury or mucosal exposure should be screened.

New Treatment Choices

The advent of direct acting antivirial (DAA) drugs has been a paradigm shift in HCV treatment. These powerful agents not only dramatically increase the cure rate for patients, but also have fewer side effects than older drugs, such as ribavirin and interferon. The DAA era officially began in 2011, when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved boceprevir and telaprevir, both protease inhibitors, according to the American Liver Foundation. Since then, many more medications have come to market. Some of them are able to produce a sustained viralresponse—meaning no detectable virus— in 95–100% of patients in clinical trials.

New FDA approvals for HCV drugs have kept coming in recent years. In 2013, FDA approved a once-daily protease inhibitor, simeprevir, as well as sofosburvir, a polymerase inhibitor. The following year FDA approved a four-drug regimen of ombitasvir, paritaprevir, ritonavir, and dasabuvir. Then in 2015, the agency approved daclatasvir, as well as a new combination of ombitasvir, paritaprevir, and ritonavir. Most recently, FDA in January 2016 approved an elbasvir and grazoprevir combination.

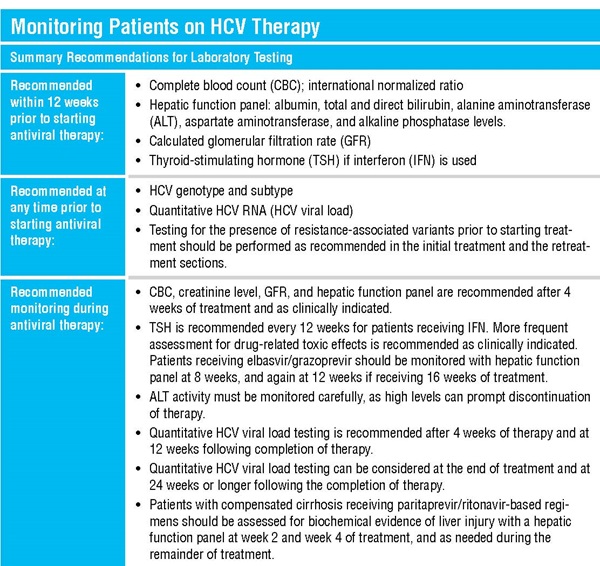

New drugs will continue to mean changes for testing as well (See sidebar). For example, current approved treatments are not equally effective depending on a patient’s viral genotype, requiring testing to determine the genotype and subtype of the virus before treatment starts. But researchers have reported that the combination of the investigational therapy sofosbuvir-velpatasvir was effective for all strains of HCV, possibly eliminating the need to test for the viral genotype (N Engl J Med 2015;373:2599–607). Gilead filed a new drug application for the sofosbuvir/velpatasvir combination in October 2015, to which FDA granted a priority review designation for breakthrough drugs in January 2016, according to the company.

A Pivotal Moment for Laboratory Medicine

The evolving HCV treatment landscape, changing clinical guidelines, and the growth of molecular testing all are having an impact on laboratory medicine. Even so, arguably the most critical issue is HCV prevention and screening, Clarke emphasized. “I hope that attendees of this scientific track take away an appreciation of the complexity of the issues pertaining to HCV and an understanding of the potential impact of HCV on public health and the cost of medical care if an adequate testing and prevention strategy isn't developed,” he said. “One of the biggest challenges in HCV pertains to laboratory medicine: screening and early detection before the infection leads to cancer. Antiviral therapy only works if you can identify the people that need it.”