Cultural competency in healthcare is the ability of health systems to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs, and behaviors, including tailoring delivery to meet patients’ social, cultural, and linguistic needs (1). Some prefer the term “cultural humility,” which implies a commitment to learning and improvement rather than mastery (2−3).

Improving the cultural competency of providers may help improve care outcomes among marginalized populations (4), including sexual and gender minorities, such as those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ). These populations face significant health disparities as well as discrimination, ignorance, bias, and even abuse from healthcare providers (5). Focusing on improved knowledge of gender diversity is especially important as social acceptance and awareness of transgender individuals have lagged behind the acceptance of people with diverse sexualities (6).

Although efforts have been made in the healthcare community to promote quality educational resources for healthcare professionals about cultural competency, they primarily have focused on education for students and patient-facing advanced medical professionals, such as medical students, physicians, nurses, and dentists. Educating laboratory medicine professionals, especially patient-facing staff such as phlebotomists, on how to interact with gender-diverse patients is a significant step towards improving healthcare for this patient population (7).

EDUCATION FOR THOSE WHO NEED IT MOST

It is crucial that phlebotomists are fully equipped to interact with transgender patients in a professional, courteous, and dignifying manner. In the field of phlebotomy, there are multiple barriers to quality care for transgender patients, such as a lack of understanding of appropriate terminology, possible discrepancies between legal and preferred name and gender, and challenges with urine collection instructions (such as inappropriate gendered instructions) (8−10).

Educating phlebotomists on appropriate gender terminology and how to have respectful interactions with transgender patients creates an environment of inclusion and openness for these patients. This improves care by decreasing the anxiety and avoidance associated with interacting with the healthcare system (9−11).

Members of the transgender community who are prescribed gender-affirming hormonal therapy will require a significant amount of interaction with phlebotomists, especially during the evaluation of therapeutic hormone concentrations (12). Ensuring that patients are comfortable in their healthcare environment and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship with providers at all levels of care is essential to improving patient outcomes for gender-diverse people.

HOW TO DEVELOP EDUCATION ON CULTURAL COMPETENCY

While phlebotomy staff must demonstrate gender-cultural competency, how to provide adequate education remains a challenge. To date, no universally accepted standard dictates what or how phlebotomy staff should be taught about conducting culturally appropriate interactions with members of the gender-diverse community. This means that details of the staff training process are decided by their respective institutions, often at the department level.

Fortunately, there are some general guidelines that institutions can tailor for their staff. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health Global Education Institute (WPATH GEI) has a robust certification program that strives to advance knowledge, skills, and cultural awareness around four core competencies: the caregiver/care receiver relationship, content knowledge, interdisciplinary practice, and professional responsibility. Structuring a phlebotomist-focused transgender cultural education program around these four competencies is an excellent place to begin.

Mandi Pratt-Chapman, PhD, and colleagues also published consensus recommendations for developing and implementing an LGBTQ cultural competency education program (13). The consensus standards were determined by a group of experts with diverse professional roles, work settings, gender identities, sexual orientations, and racial or ethnic identities. They summarized five key recommendations for all training initiatives:

- Training must be audience-specific, which may require conducting a needs assessment. Additionally, the goals of the training should be clearly delineated and applicable to the learners, and it is critical to communicate why the education is vital for the learners specifically.

- The curriculum should include foundational concepts (e.g., social determinates of health, disparities, and intersectionality), terminology (e.g., transgender, gender-expression, and dysphoria), and methods to avoid stereotyping and be resilient in challenging situations.

- The education ought to employ effective modes of delivery by using multiple strategies for interactive learning (multimedia, case studies, narrative, and self-reflection).

- Choose trainers with expertise in applicable sexual and gender minority healthcare topics and try to include trainers with diverse lived experiences and skill sets. Importantly, the trainers should be able to respond to strong emotional reactions.

- Evaluate the education to assess effectiveness.

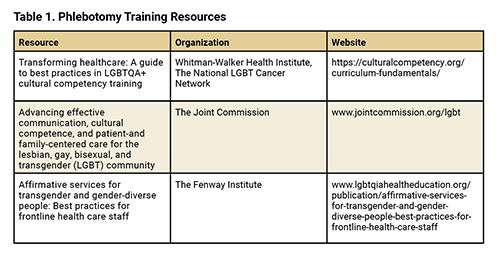

The recommendations by Pratt-Chapman and core competencies from WPATH GEI provide an excellent framework for developing a transgender-oriented cultural competency education program, but they omit the specific content needed to populate the training. Several reputable organizations provide this information for use and adoption (Table 1).

A CALL TO ACTION

Cultural competency education in phlebotomy is the responsibility of the lab medicine community. We understand the unique challenges this may present to phlebotomists, and how their typical practices—showing respect by using the terms “sir” or “ma’am,” for example—may not work for gender-diverse patients. Additionally, there are regulatory concerns related to patient identification when the preferred name and legal name do not match. It is the task of laboratory leaders to ensure phlebotomy staff have the tools they need to overcome these challenges and interact with gender-diverse patients in a respectful and affirming manner.

References

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499.

- Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education [eng]. J Health Care Poor Underserved 1998, doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233.

- Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural Humility: A Concept Analysis. J Transcult Nurs 2016, doi: 10.1177/1043659615592677.

- Henderson S, Kendall E, See L. The effectiveness of culturally appropriate interventions to manage or prevent chronic disease in culturally and linguistically diverse communities: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community 2011, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00972.x.

- Arnold E, Dhingra N. Health Care Inequities of Sexual and Gender Minority Patients [eng]. Dermatol Clin 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.10.002.

- GLAAD. Executive Summary: Accelertaing Acceptance 2023. https://glaad.org/publications/accelerating-acceptance-2023 (Accessed January 2024).

- Imborek KL, Nisly NL, Hesseltine MJ, Grienke J, Zikmund TA, Dreyer NR, Blau JL, et al. Preferred Names, Preferred Pronouns, and Gender Identity in the Electronic Medical Record and Laboratory Information System: Is Pathology Ready? [eng]. J Pathol Inform 2017; doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_52_17.

- Gupta S, Imborek KL, Krasowski MD. Challenges in Transgender Healthcare: The Pathology Perspective [eng]. Lab Med 2016; doi: 10.1093/labmed/lmw020.

- Goldstein Z, Corneil TA, Greene DN. When Gender Identity Doesn't Equal Sex Recorded at Birth: The Role of the Laboratory in Providing Effective Healthcare to the Transgender Community [eng]. Clin Chem 2017; doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.258780.

- Kruse MI, Bigham BL, Voloshin D, Wan M, Clarizio A, Upadhye S. Care of Sexual and Gender Minorities in the Emergency Department: A Scoping Review. Ann Emerg Med 2022; doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.09.422.

- Goldberg A. Our Transgender Language Choices Make All the Difference. The ASHA Leader 2019.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, Hannema SE, Meyer WJ, Murad MH, Rosenthal SM, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Endocr Pract 2017; doi: 10.4158/1934-2403-23.12.1437.

- Pratt-Chapman ML, Eckstrand K, Robinson A, et al. Developing Standards for Cultural Competency Training for Health Care Providers to Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual Persons: Consensus Recommendations from a National Panel. LGBT Health 2022; doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2021.0464.

Gabrielle Winston-McPherson, PhD, DABCC is the associate director of chemistry at Henry Ford Health in Detroit, Michigan. +Email: [email protected]

Henrietta (Fasanya) Maku, MD, PhD, is a pathology resident at Houston Methodist Hospital in Houston, Texas. +Email: [email protected]