Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.242057

An 18-year-old adolescent male presented to our emergency department complaining of chest pain that started about 2 days earlier and remained unchanged. Chest x-rays revealed a right apical pneumothorax. The patient did not use any medication. Two months earlier he had presented to the emergency department with a similar episode that resolved spontaneously.

Student Discussion

Student Discussion Document (pdf)

Roberto Dongilli,1 Claudio Crivellaro,2 Federica Targa,3 Giulio Donazzan,1 and Markus Herrmann3*

Departments of 1Pulmonology, 2Internal Medicine, and 3Clinical Pathology, Bolzano Hospital, Bolzano, Italy.

*Address correspondence to this author at: Clinical Pathology, Bolzano Hospital, Bolzano, Italy; e-mail: [email protected].

Case Description

An 18-year-old adolescent male presented to our emergency department complaining of chest pain that started about 2 days earlier and remained unchanged. Chest x-rays revealed a right apical pneumothorax. The patient did not use any medication. Two months earlier he had presented to the emergency department with a similar episode that resolved spontaneously. Blood testing performed at the time of presentation showed severe hypokalemia with a potassium concentration of 2.5 mmol/L. He was admitted to our respiratory unit.

He was 180 cm (70.9 in) tall and weighed 64 kg (141 lb, body max index 19.8 kg/m2). He was in good general health, and the physical examination was unremarkable. A renal ultrasound was normal. He noted an unintentional weight loss of 7 kg (15.4 lb) over the last 36 months. Furthermore, he reported fatigue and muscle weakness. His personal history and family history were unremarkable. He was delivered naturally at term and developed normally during childhood and puberty.

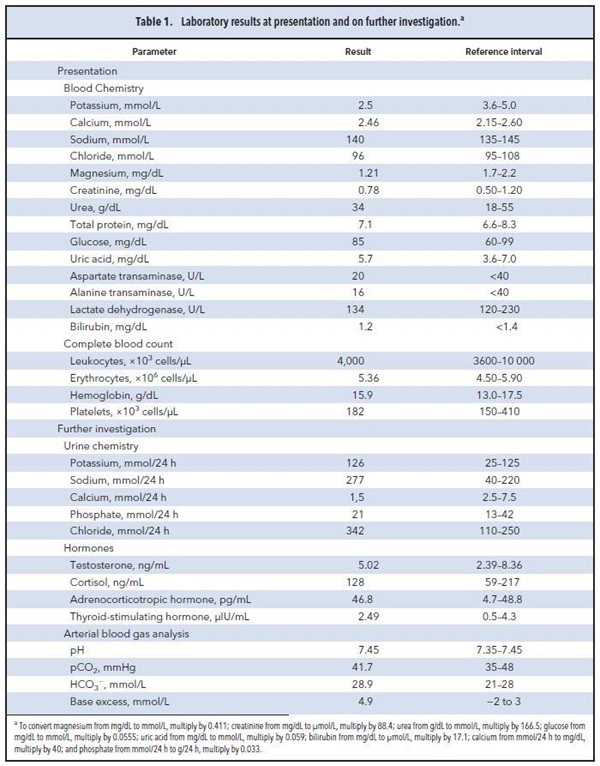

Further blood tests revealed moderate hypomagnesemia of 1.2 mg/dL [0.5 mmol/L; reference interval 1.7–2.2 mg/dL (0.7– 0.9 mmol/L)]. Arterial blood gas analysis showed metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.46, bicarbonate 28.9 mmol/L). Sodium, chloride, and calcium were within reference intervals. Renal function, fasting blood glucose, and a complete blood count were normal. Table 1 provides a selection of relevant laboratory results at presentation and during follow-up.

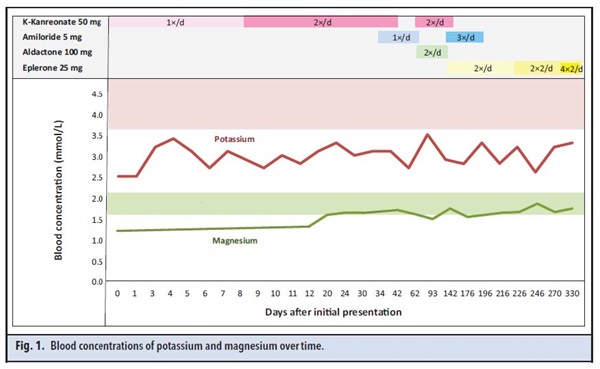

As recommended by the British Thoracic Society, the patient was scheduled for video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (1). Before surgery, an endocrine specialist was consulted to further investigate the cause of the patient’s hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia. The spontaneous pneumothorax was unrelated to the abnormal electrolyte results and is not further discussed here. The patient’s pronounced hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia were initially treated with potassium canrenoate, potassium chloride, and magnesium (Fig. 1). With this therapy, serum potassium improved and stabilized at 2.8 –2.9 mmol/L. Subsequently, amiloride was added to the patient’s therapy, which led to a further improvement of serum potassium. However, he reported increasing fatigue, which led to the discontinuation of potassium canrenoate, without which correction of potassium was insufficient. Therefore, it was decided to replace amiloride by potassium canrenoate and spironolactone. Three months after the initial presentation, his potassium had risen to 3.4 mmol/L.

Within 10 weeks after the initiation of spironolactone therapy, he developed gynecomastia, a well-known side effect of this drug. Consequently, spironolactone was again replaced by amiloride, although at a higher dose. As serum potassium remained low, at approximately 2.8 mmol/L, he was switched from amiloride to eplerenone, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist that does not cause gynecomastia. Potassium and magnesium supplementation were continued as before. With this therapy, serum potassium and magnesium concentrations stabilized near the lower limit of the reference interval.

Reference

- Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic pleural disease guideline 2010 BTS. Thorax 2010;65:18 –31.

Questions to Consider

- What are the most common causes of hypokalemia?

- Which laboratory tests can differentiate between renal and nonrenal causes of potassium loss?

- Describe some rare genetic causes of hypokalemia?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the March 2016 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.242057

Copyright © 2016 American Association for Clinical Chemistry