Summary

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.152447

A 21-year-old woman presented with a 5-day history of loss of appetite, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. On examination, she appeared acutely ill, with jaundice and right-sided hypochondrial tenderness. The stigmata of chronic liver disease were absent, and the results of her neurologic examination were typical. She had previously been well except for bouts of somnolence with occasional emesis during the previous year. There was no history of recent travel, alcohol or illicit drug use, or liver disease in her family. Viral hepatitis was considered the most likely diagnosis, but the patient's clinical deterioration necessitated hospital admission a day later.

Student Discussion

Student Discussion Document (pdf)

Nicholette M. Oosthuizen*

Department of Chemical Pathology, University of Pretoria/National Health Laboratory Service, Tshwane Academic Division, Pretoria, South Africa.

* Address correspondence to the author at: P.O. Box 2034, Department of Chemical Pathology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 0001. Fax +27-12-328-3600; e-mail [email protected].

Nonstandard abbreviations: URL, upper reference limit; RI, reference interval; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase.

Case Description

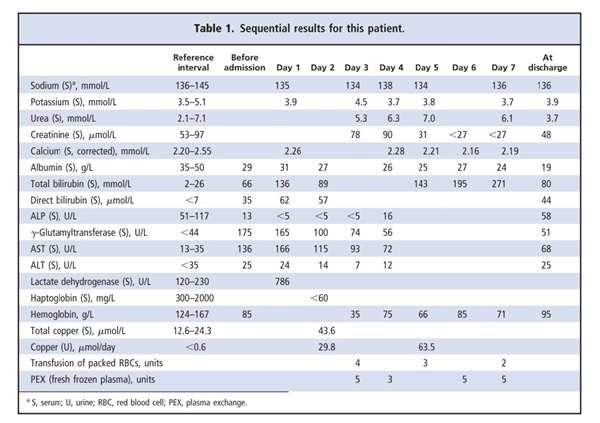

A 21-year-old woman presented with a 5-day history of loss of appetite, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. On examination, she appeared acutely ill, with jaundice and right-sided hypochondrial tenderness. The stigmata of chronic liver disease were absent, and the results of her neurologic examination were typical. She had previously been well except for bouts of somnolence with occasional emesis during the previous year. There was no history of recent travel, alcohol or illicit drug use, or liver disease in her family. Viral hepatitis was considered the most likely diagnosis, but the patient’s clinical deterioration necessitated hospital admission a day later. The results of serology tests for acute infection with hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, or Epstein–Barr virus were negative, and the complete blood count revealed a macrocytic anemia. Liver function tests revealed the following: total bilirubin, 136 μmol/L [upper reference limit (URL),2 26 μmol/L]; direct bilirubin, 62 μmol/L (URL, 7 μmol/L); albumin, 31 g/L [reference interval (RI), 35–50 g/L]; γ-glutamyltransferase, 165 U/L (URL, 44 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 166 U/L (URL, 35 U/L); alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 24 U/L (URL, 35 U/L). Serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was noteworthy for being undetectable (<5 U/L; RI, 51–117 U/L) on 3 consecutive days. Methodologic interference in the ALP assay by anticoagulants, such as EDTA and fluoride, was excluded on the basis of sodium, potassium, and calcium concentrations that were within reference intervals. Evidence of hemolysis was provided by the results for serum lactate dehydrogenase (786 U/L; RI, 120–230 U/L) and haptoglobin (<60 mg/L; RI, 300–2000 mg/L). The hemoglobin concentration decreased from 83 g/L to 35 g/L (RI, 124–167 g/L), requiring transfusion of 9 units of packed red blood cells. The patient also received 18 units of fresh frozen plasma during 4 plasma-exchange procedures. Although citrate chelation after transfusion of blood products may cause low ALP activity, undetectable ALP activity had been documented before the transfusions. The results for the direct Coombs test were negative, and the international normalized ratio was 2.0 (RI, 0.9–1.2). An initial serum urea concentration of 5.3 mmol/L (RI, 2.1–7.1 mmol/L) and a creatinine value of 78 μmol/L (RI, 53–97 μmol/L) indicated that the patient’s renal function was well preserved (Table 1).

Questions to Consider

- What are the causes and characteristics of fulminant hepatic failure?

- Which causes of fulminant hepatic failure are associated with hemolysis?

- What are the causes of low ALP activity, and how are they related to fulminant hepatic failure?

Final Publication and Comments

The final published version with discussion and comments from the experts appears

in the March 2011 issue of Clinical Chemistry, approximately 3-4 weeks after the Student Discussion is posted.

Educational Centers

If you are associated with an educational center and would like to receive the cases and

questions 3-4 weeks in advance of publication, please email [email protected].

AACC is pleased to allow free reproduction and distribution of this Clinical Case

Study for personal or classroom discussion use. When photocopying, please make sure

the DOI and copyright notice appear on each copy.

DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.152447

Copyright © 2011 American Association for Clinical Chemistry