In days gone by, when the clinical diagnostic world was less complicated than today, primary care physicians easily could keep up with 20 or so key lab tests needed to diagnose most conditions they would run across in everyday patient care. Now, however, given a dizzying array of test choices and the hubbub of ever-busier practices, doctors need help in better selecting and interpreting lab tests. A major Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initiative and other complementary efforts are emphasizing the essential role laboratorians play in guiding physicians to use tests more effectively, and are calling for the profession to do more now to support physicians even as they focus on broader solutions to this admittedly complicated issue.

"Labs have added a huge number of tests over the years—especially in the past decade—and for physicians to be familiar with the ordering, interpreting, and timing of old and new tests is a daunting task," explained Marisa Marques, MD, professor of pathology at the University of Alabama School of Medicine in Birmingham. "It's not even humanly possible to expect that physicians, especially those in primary care, will know how to use all these tests. On the other hand, the more choices doctors have, the more likely they are to make the wrong choice, and we see many inappropriate orders coming through the lab every single day. But laboratorians know the tests, and our message is that every single person who works in a lab should play an active role in helping the patient get the right diagnosis at the right time. This is really important as we move forward to improve understanding and utilization of laboratory tests for patient care."

Assessing the Evidence Base

Marques is a member of CDC's Clinical Laboratory Integration into Healthcare Collaborative (CLIHC), an ambitious project of the Agency's Division of Laboratory Science and Standards aimed at filling gaps that impede practicing clinicians from effectively utilizing lab services for better patient care. CLIHC grew out of a 2007 institute CDC convened on critical issues in laboratory medicine practice, and it is in the process of implementing a series of measures aimed at better understanding and addressing diagnostic errors caused by misordering and misinterpreting lab tests.

One of CLIHC's key tasks has been to uncover and add to the evidence base on this issue. A review of the scientific literature extending back 40 years found a modest amount of research linking errors in test selection and result interpretation to poor patient outcomes. However, starting in the decade of the 2000s, more articles began to appear showing both that patients are harmed by such mistakes just like they can be harmed by surgical and pharmaceutical errors and proposing solutions to this issue. "It's convenient to split this problem into ordering the test appropriately and interpreting the results correctly. There is some literature on rates of misordering or ineffective ordering, but it's hard to put a single number on it. Most of the studies have focused for practical reasons on one particular test in one particular setting," said Brian Jackson, MD, MS, chief medical information officer at ARUP Laboratories in Salt Lake City. "What's important is that over the last 15 years, there's been more of a focus not only on the problem but also ways of dealing with it." A consultant to CLIHC, Jackson also is a member of CLN's Patient Safety Focus editorial board.

CLIHC member Michael Laposata, MD, PhD, spoke about the evolving understanding of the lab's role in diagnostic errors. "For the longest time I had been given the impression that most doctors think that if a mistake was made in ordering lab tests it wouldn't be a life-or-death issue, but rather, an inexpensive lab test would be ordered unnecessarily. But over the past decade we've learned that when people don't order the right test or order too many tests, the consequences can be devastating, even life-threatening," he said. Laposata is Edward and Nancy Fody professor and executive vice chair of pathology, microbiology, and immunology at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville.

The Sources of Errors

CLIHC member Paul Epner, MBA, MEd, and Michael Astion, MD, PhD, chair of CLN's Patient Safety Focus editorial board, recently proposed a framework for understanding the lab connection to diagnostic errors (CLN 2012;38:17). They identified five test-related issues that can result in diagnostic errors, including ordering an inappropriate test, not ordering an appropriate test, not properly using the result from an appropriately ordered test, and delays or errors in producing results for appropriately ordered tests. "Lab directors own the last issue—that the appropriate test result is not accurate," said Epner. "However, the first three are physician-related. Doctors need help, and if we don't focus on collaborating with them, we can't affect those first three issues as much as we'd like."

A Chicago-based independent consultant interested in strengthening the link between lab services and patient outcomes, Epner is particularly intent on driving the research agenda around the lab's role in effective test utilization. "We focus so much on over-testing, and on a volume basis over-testing is a bigger problem than under-testing. But from a patient harm perspective, I don't think we know whether over- or under-testing has a greater impact. I think people have jumped to the wrong conclusion," he explained.

Epner also is a key contractor for an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-funded study involving lab risk assessment to reduce diagnostic error. This initiative has developed and piloted at three sites a risk assessment tool for referral testing, as well as a survey and quiz for physicians on test ordering, along with resources on test ordering and interpretation. "When you think about send-out testing, it's often low-volume, expensive tests that the clinician expects to provide high-value, very specific information that could make a big difference in treatment selection or diagnosis. But the clinician's reduced familiarity with the test also means there is an increased risk of diagnostic errors," Epner explained. "The risk assessment tool we're developing is designed to help organizations look at themselves in the area of send-out testing to see if there's a problem."

What Doctors Think

In the vein of understanding how laboratorians can collaborate better with doctors, CLIHC sought feedback from primary care practitioners, first through a series of small focus groups, and more recently via a survey of 1,200. The results of both these efforts have been eye-opening, according to Epner. "Some of the anecdotal comments we received from the focus groups were pretty disheartening. For example, one clinician said, ‘when I talk to a radiologist or pharmacist, I'm talking to a colleague. When I call the lab it's like talking to a black box'," he explained.

Josh Peterson, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of medicine and biomedical informatics at Vanderbilt, echoed those sentiments during an Afternoon Symposium at this year's AACC Annual Meeting. "When CT scans and MRIs became commonly available, radiologists increasingly became a source of clinical advice, and they were rewarded for it so that radiology is now a highly sought after specialty. I think changing the focus of laboratory directors to providing clinical support for people like me could really change your field," he said. "In regard to imaging studies, there is virtually always an expert radiologist available to answer my questions. They are also proactive about catching test orders that don't answer the clinical question of interest. On the other hand, when I order a laboratory study, I simply have a huge list of tests to choose from, without any advice about the right one to select."

Preliminary results from CLIHC's physician survey also underscored the lab-physician collaboration gap. When respondents had questions about the correct test to order, they were most likely to review e-references and least likely to consult a lab professional. Similarly, if they had an issue with interpreting a result, they were most likely to review the patient's history and follow-up with the patient, and least likely to ask a lab professional. The survey findings—still being analyzed and expected to be published in the future—are not all gloom-and-doom for laboratorians, however. "What's interesting, and we were disappointed about it, but one of the things doctors were not likely to do is ask a lab professional. That was the lowest tactic they chose for both test ordering and result interpretation. But when they did get in touch with a lab professional they found those contacts helpful," explained Julie Taylor, PhD, CDC's project lead for CLIHC. "It's important for laboratorians to know that if they develop this relationship, doctors find it very useful."

What's in a Name?

CLIHC also recognized that some physicians understandably get hung up on lab test nomenclature. A project examining this issue found wide inconsistencies in test nomenclature to be a significant problem likely to impact patient safety. For example, CLIHC members identified at least 18 different titles for vitamin D-related tests (see Box, p. 4). "The nomenclature problem is a major one because no one has been forced by a higher body to sit down and resolve the confusion around test names and abbreviations. And too many people think that the name and abbreviation they are using for a test has to be the best one. I can tell you that the CLIHC group is having active discussions about how to address this huge problem," said Laposata.

What's in a Name?

An Example of the Confusion

The existing nomenclature options for vitamin D and its multiple forms illustrates why physicians can be confused about ordering appropriate tests.

- Vitamin D2

- Ergosterol

- Vitamin D3

- Cholecalciferol

- 25-OH vitamin D2

- 25-OH vitamin D3

- 25-OH vitamin D

- 25 hydroxy vitamin D2

- 25 hydroxy vitamin D3

- 25 hydroxy vitamin D

- 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D2

- 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D3

- 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D

- 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D2

- 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3

- 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D

- Vitamin D 25 Hydroxy D2 and D3

- Vitamin D 1,25 Dihydroxy

Guiding Test Choices

Inconsistent clinical guidelines and testing algorithms—when they exist at all—further obscure physicians' ability to make the right test choice and understand the result. Peterson explained that while doctors like the concept of reflex testing, the pressures of daily practice—and sometimes the lack of a clear stepwise testing pathway—tips the scales towards panel testing. "We end up ordering a lot of laboratory panel tests all day; this is well-described as the shotgun method, and it saves me time, but it costs the system money," he observed.

Laposata, Marques, and their colleague, Oxana Tcherniantchouk, MD, recently took the lead, in collaboration with CDC, in developing what they hope will be the first of many algorithms that walk physicians through coagulation-related diagnostic test ordering and interpretation. The fruit of this effort, PTT Advisor, is a mobile app for iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch that addresses tests needed to evaluate patients who have a prolonged partial thromboplastin time but normal prothrombin time. (See Box, below)

PTT Advisor

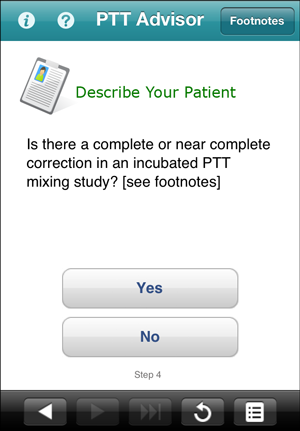

Innovative Mobile App Aids in Coagulation Testing Decisions

Lack of clear diagnostic algorithms around test selection and result interpretation has been cited as a contributor to physicians inappropriately ordering and interpreting diagnostic tests. A unique collaboration between three pathologists who specialize in coagulation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has taken the first step in what the participants hope will be a series of practical tools to help physicians use tests more efficiently.

PTT Advisor is an interactive mobile app for iPhone, iPod Touch, or iPad available for free download from the Apple App Store.

PTT Advisor is an interactive mobile app for iPhone, iPod Touch, or iPad available for free download from the Apple App Store.

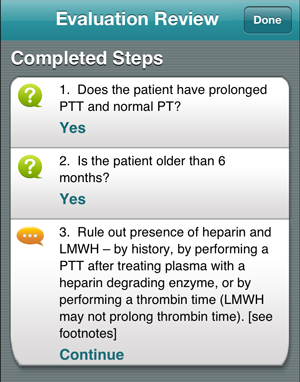

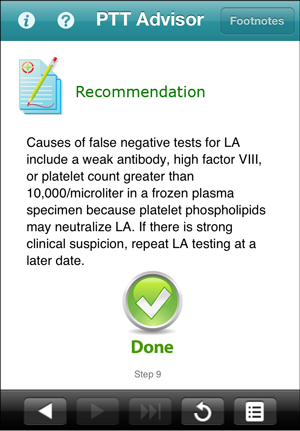

This simple, easy-to-use tool navigates users quickly through a clinical decision tree to evaluate pediatric or adult patients who have prolonged partial thromboplastin times but normal prothrombin times.

This simple, easy-to-use tool navigates users quickly through a clinical decision tree to evaluate pediatric or adult patients who have prolonged partial thromboplastin times but normal prothrombin times.

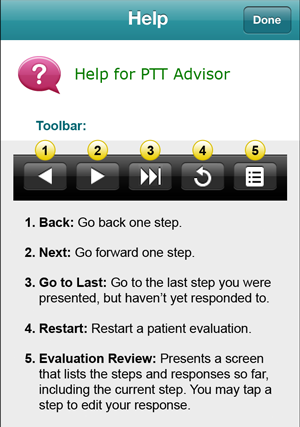

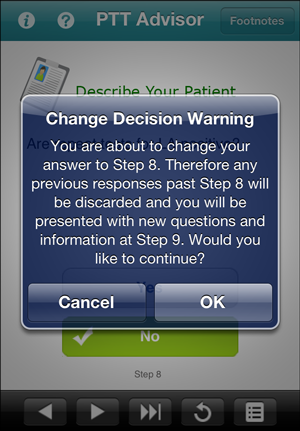

The nine-step process enables clinicians to modify answers quickly and review selections at any point. Users respond to a structured series of questions, and receive additional information and footnotes at key decision points.

The nine-step process enables clinicians to modify answers quickly and review selections at any point. Users respond to a structured series of questions, and receive additional information and footnotes at key decision points.

"We're going to try to put together more and more such algorithms. Our goal is to cover the entire field of coagulation," said Michael Laposata, MD, PhD, who co-developed the algorithm for PTT Advisor with colleagues Marisa Marques, MD, and Oxana Tcherniantchouk, MD. A team at CDC, including the Agency's Informatics R&D Laboratory, worked on the technology side. The finished product—the first of its kind from CDC—has been available for download since July.

"We're going to try to put together more and more such algorithms. Our goal is to cover the entire field of coagulation," said Michael Laposata, MD, PhD, who co-developed the algorithm for PTT Advisor with colleagues Marisa Marques, MD, and Oxana Tcherniantchouk, MD. A team at CDC, including the Agency's Informatics R&D Laboratory, worked on the technology side. The finished product—the first of its kind from CDC—has been available for download since July.

PTT Advisor is a deliverable from the Agency's Clinical Laboratory Integration into Healthcare Collaborative (CLIHC), an ambitious project of the CDC's Division of Laboratory Science and Standards aimed at filling gaps that impede practicing clinicians from effectively utilizing lab services for better patient care.

For more information about PTT Advisor visit the Apple App Store.

PTT Advisor is a deliverable from the Agency's Clinical Laboratory Integration into Healthcare Collaborative (CLIHC), an ambitious project of the CDC's Division of Laboratory Science and Standards aimed at filling gaps that impede practicing clinicians from effectively utilizing lab services for better patient care.

For more information about PTT Advisor visit the Apple App Store.

The Medical Education Connection

Another important factor hindering physicians from making the best use of diagnostic testing is the limited amount of laboratory medicine covered in medical school. CLIHC is in the process of surveying all 133 medical and 23 osteopathic schools in the U.S. to learn how much students are taught about ordering and using lab tests, but preliminary data are not encouraging. "The problem is, we don't teach students how to interpret lab test results or how to pick them. Overall, there are about nine hours spent teaching the whole of laboratory medicine. The comparison is we're spending 61 to 302 hours in anatomic pathology," explained Laposata. "However, to pass anatomic pathology, you've got to pass a test, and if students can't recognize what they're viewing via microscope, they fail. But guess what? There are no tests for lab medicine. It's kind of thrown in at the end of the second year. In a few moments students hear about test sensitivity for diagnosis. Yet once they get out in practice, doctors are not going to look through a microscope to come up with their own findings. However, they will order tests from a lengthy menu. So there's clearly a mismatch in what we are teaching in path-ology to prepare students for practice."

Limited teaching about laboratory testing in medical school was top on the minds of CLN readers. In an online survey, nearly three-quarters of respondents rated this as highly important in contributing to less-than-ideal physician utilization of laboratory testing, placing it at the top of 14 key issues (see Survey, below).

The Personal Touch

As CLIHC continues to assemble data and develop long-term strategies around helping physicians use lab tests more effectively, there are numerous things laboratorians can do now to make a difference. First and foremost, experts urged them to get out of the lab and directly interface with their medical colleagues. "One of the easiest things we'd like all laboratorians to do is be available and visible to all medical staff, and to be very open to being called and consulted," said Marques. "This is a challenge because most people who work in labs don't necessarily expect to do that. However, as they become known and become an integral part of the healthcare team, clinicians will feel comfortable asking when they're uncertain about test ordering or interpretation."

Experts also advised making knowledgeable experts readily available, with the emphasis on readily. "The key is to make it incredibly easy for a doctor to get hold of an expert in the lab and get an answer to his question. Carrying a pager is not really enough. Carrying a cell phone helps. Organizations with residents or larger pathology groups can organize this around a formal on-call process, but you have to monitor the quality," said Jackson. "You have to make sure that doctors get their answers within a short period of time, monitoring the rate and turnaround time of call resolution just like a commercial call center would do. Monitoring the performance of your doctor answering service—or whatever you call it—is critical."

IT to the Rescue

Epner believes certain information technology (IT) solutions can be brought to bear relatively easily, quickly, and effectively. For example, he recommends tweaking interpretive comments to go beyond stock phrases. Otherwise, "clinicians report getting desensitized. They see the same comment over-and-over again, and they don't even read it. So providing help with interpretation is something we can do today," he said.

Epner also advocates systemizing the process of flagging inappropriate test utilization. "Using data mining activities to uncover patterns of inappropriate testing and reporting that back to clinicians can be effective. There's peer-reviewed literature that suggests when you give performance feedback to departments of physicians, you don't have to judge it, you just have to provide it. They'll figure it out," he said. "If one clinician is ordering twice as many troponins as his five colleagues, that will normalize."

A Team Approach

Other robust IT capabilities—like organizing into one clinical record lab data collected from different patient encounters at different clinical sites—also have been cited as having the potential to improve diagnostic test utilization. However, since these solutions can be complicated and slow in coming, Jackson and others urged laboratorians to focus their efforts on organizational solutions. "This isn't best thought of as a lab issue; it's a systems issue. Medical care in the U.S. is still primarily organized not as a team effort but as an individual effort by doctors, and in most hospitals there are not good systems in place for collaboration around patients," explained Jackson. "However, under new accountable care models, organizations will accept responsibility for the quality of a patient's care in a comprehensive way, rather than as just discrete episodes. That means doctors will need to be in oversight positions where they'll be in charge of monitoring peers, on a team level, to measure and improve healthcare."

Vanderbilt is one of several healthcare systems on the vanguard of taking a team approach to the diagnostic process, with lab medicine as a key player. Starting with coagulation in 2010, it has established four diagnostic management teams, with plans in the works for at least three more. The purpose of the teams is to help doctors diagnose patients' conditions more quickly and accurately. In the case of coagulation, the effort also has boosted efficiency and improved the accuracy of diagnosis. In hematopathology, it has saved several hundred thousand dollars by eliminating unnecessary molecular tests.

"Trainees and the laboratory director read the clinical record and formulate an expert-driven, patient-specific narrative about what all the test results mean. Every morning, a resident or fellow on the coagulation service connects with the technologist in the special coagulation laboratory about the evaluations in progress," explained Laposata. "The trainee reads the clinical record and reviews the laboratory data for each case, and at 4 p.m. provides a tentative narrative interpretation of the test results. The final report is generated in rounds with the laboratory director. In these rounds, we usually explain all the data from the clinical laboratory in an interpretation that anyone caring for the patient, including the nursing staff, would understand and react to appropriately."

The process not only focuses the entire team on each patient's diagnostic pathway, but also is an important means of feedback to physicians about their ordering practices. For example, if a test has been ordered that is not particularly germane to the patient's workup, Laposata will indicate so in the interpretive comments. "When there's a test ordered that's not useful, I will often add at the end something like, ‘The assay for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is likely to be uninformative in this situation'," he explained.

How to Learn More and Get Involved

- Downloadable recordings of the Symposium, "Improving Physicians' Utilization of Laboratory Testing for Better Patient Outcomes," from AACC's 2012 Annual Meeting are available for purchase at the AACC Store.

- An archive of Dr. Michael Laposata speaking on "How Diagnostic Management Teams Can Help Improve Patient Safety" from the AACC Thought Leadership Series, is available online.

- The fifth Diagnostic Error in Medicine conference is taking place November 11–14, 2012 in Baltimore, Md. Paul Epner is co-chair of the planning committee for this Johns Hopkins University-sponsored event. He and Dr. Brian Jackson will speak on test utilization. Go to the John Hopkins website.

- Paul Epner asks laboratorians interested in participating in his research initiative "Improvements in Test Selection and Result Interpretation" to contact him at [email protected].

- More information about CLIHC is available online. Project lead for CDC, Julie Taylor, invites laboratorians interested in learning more about CLIHC to contact her at [email protected].

The Vital Role of Technologists

Experts were quick to dispel any notion that helping physicians better utilize tests is solely the domain of pathologists and lab directors. "Medical technologists know these tests and they can participate in the areas where they're specialists," said Marques. "They should stay vigilant so that they can recognize orders that appear to have a less-than-optimal combination of tests and discuss with their medical directors when they see something that could be improved. Alternatively, technologists should feel comfortable contacting ordering physicians directly and telling them about newer or lesser known tests. I recognize that many technologists will need time to get used to the idea of being laboratory consultants, but they have an understanding of tests that many physicians lack. For better patient care, technologists have an enormous role to play in the future."

Epner invited laboratorians of all stripes to join in research that substantiates the lab's role in reducing diagnostic error, and in educating peers. Collectively, these efforts can make an enormous mark on test utilization and patient safety.

CLN Survey

What Leads Doctors to Less-than-Optimal Test Utilization?

During a symposium at this year's AACC Annual Meeting in July, the speakers polled the audience informally on several key questions that impact how well physicians use lab tests. CLN posed these same questions to our readers in an online survey, conducted between July 26 and August 7, 2012. More than 300 individuals participated.

The single most important issue respondents identified as leading to ineffective test ordering is limited teaching about laboratory medicine in medical school. Nearly three-quarters of respondents rated it as highly important. This comment was representative of many: "Medical students have little desire to learn about lab testing until they reach the wards. At this point they are often taught by physicians who learned their lab info one or more decades ago. The lab needs to be visible on rounds."

Following as a close second was the failure to collectively organize best practices around lab test selection and result interpretation, which nearly 72% of participants rated as highly important. Respondents noted the difficulty in determining best practices, which can vary significantly between institutions. However, they also cited the potential for significant savings by eliminating over-testing with even very inexpensive tests.

Other issues leading to less-than-ideal use of tests included: lack of valuable clinical decision support tools to aid physicians in selecting laboratory tests; limited use of diagnostic algorithms to direct appropriate test selection; lack of IT infrastructure that makes it easy to appropriately select the correct test(s) and interpret the results; perception of the clinical laboratory as a cost center with no ability to provide cost offsets in other areas; and inability to organize into one clinical record laboratory data collected from different patient encounters at different clinical sites, with roughly 60% of respondents rating each as highly important.

Opinion was more divided on other issues: the limited ability of clinicians to identify true experts in laboratory test selection and interpretation; the complexity of lab test names; limited information exchanged between clinicians and patients about test results; and utilization of new tests before diagnostic or prognostic utility has been firmly established in peer-reviewed literature and by medical professional societies.

Comments Reflecting the Views of Many Survey Participants

"Medical laboratory scientists are highly underused to help clinicians determine test and testing regimens."

"The lab cannot hide behind the biohazard signs. The directors, supervisors and specialists need to have time built into their schedules to mix with the ward personnel. Weekly rounding with the residents and med students is an effective method of making the lab visible and the staff a source of information."

"Physicians need to be aware of test ordering duplication. For example, ordering a point-of-care basic metabolic test and at the same time having this panel performed in the main lab. Both do not get reimbursed, and they are duplicative. If the physician is using the point-of-care results, they should be acted on immediately, with the clinical decision made at that time."

"There is still a barrier between clinicians and laboratorians, either conscious or unconscious, and this limits the ability to successfully treat patients. Cross communication is necessary to successfully follow through with patients… It will be great when all clinicians feel they can pick up the phone and ask us for information!"

Importance of Factors that Influence Physician Test Utilization

Limited teaching about lab testing in medical school

Complexity of lab test names

Inability to organize lab data from different sites into one clinical record

Utilization of new tests before diagnostic or prognostic utility has been firmly established