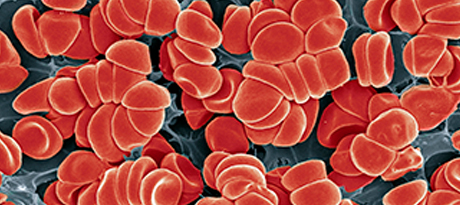

Science Photo Library - STEVE GSCHMEISSNER/Getty Images

Evidence is mounting that seriously ill COVID-19 patients develop coagulation problems, giving rise to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). This alarming trend, leading to strokes and death even among young people, raises questions over the need to treat intensive care (ICU) patients with anticoagulants—and which lab tests most effectively target DIC and monitor bleeding risk from these medications.

Studies have shown that blood clots appear in 20% to 30% of patients critically ill with the virus. In one study of COVID-19 autopsy results from a German hospital, researchers found elevated levels of D-dimer, C-reactive protein, and lactate dehydrogenase. These patients also had mild thrombocytopenia.

“COVID-19 may lead to pulmonary embolism by activating the coagulation system or causing a cytokine storm, in which high levels of proinflammatory cytokines start to attack the body’s own tissues rather than just the virus,” according to a summary of the German study. Based on these findings, the authors suggested using anticoagulant treatment in COVID-19 patients with elevated D-dimer levels.

Another recent study underscored the benefits of early thromboelastography (TEG) and D-dimer testing to identify COVID-19 patients requiring aggressive anticoagulation therapy. Researchers found that 80% of patients identified by TEG (no clot breakdown after 30 minutes) and a D-dimer level greater than 2,600 ng/mL were at higher risk for renal failure and required dialysis. This compares with 14% who tested negative on both thresholds. Patients with affirmative tests also had a 50% rate of venous blood clots.

“Even during the study time period, our institution had been increasing the dosing on medication to prevent blood clots,” Franklin Wright, MD, FACS, lead author of the study and an assistant professor of surgery at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, told CLN Stat. “We are now actively involved in at least two clinical trials involving higher-dose blood thinning medication or thrombolytic medication.”

Other research has looked at the merits of administering systemic anticoagulation therapy in COVID-19 patients. In the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, a team at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai examined the utility of anticoagulation therapy in a large cohort of more than 2,700 hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Adjusting for factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index, history of hypertension, cardiovascular issues, type 2 diabetes, anticoagulant use prior to hospitalization, and admission date, the researchers found that the therapy seemed to improve survival rates. Mortality rates were similar among intervention and control groups. However, the investigators observed a striking difference in mortality in mechanical ventilator patients who received anticoagulants versus those who did not (29.1% and 62.7% respectively). Bleeding events were slightly higher in the anticoagulant group, but not statistically significant.

Next steps are to monitor anticoagulant therapy in more than 5,000 COVID-19 patients, study co-author Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, director of the Zena and Michael A. Wiener Cardiovascular Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, said during a podcast. “Now that we have many patients on anticoagulation, we can ask a number of questions about this approach,” Fuster said. What are the actual differences in outcomes if patients receive anticoagulation or not? Which are the appropriate anticoagulants to give, alone or in combination, and at what dose? What is the timing of intervention? Such questions will eventually lead to randomized trials, which would examine the best anticoagulation therapy in hospitalized ICU patients, non-ICU hospitalized patients, and in patients after discharge.

Work will also look at therapy regimes for COVID-19 patients at home and those at high risk for the virus, Fuster said.

An international collaboration of experts also addressed this issue, publishing an evidence document on thrombotic disease of COVID-19 patients. Endorsed by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) and other groups, the document evaluated various therapeutic regimens, including low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), heparin, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

Neither therapy requires regular monitoring to show its effectiveness, Mahesh V. Madhavan, MD, a third-year cardiology fellow at the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center and co-author of the document, said in a news report. But for patients hospitalized with COVID-19, LMWH might be a better option. “Given their longer half-life, the effect of DOACs can stick around the body and increase the likelihood of bleeding, especially in circumstances where procedures are needed/likely,” he said in a Medscape interview. Another disadvantage of DOACs is they can interact with investigational COVID-19 therapies and other therapies.

Madhavan said he would be switching his own COVID-19 patients from DOACs to heparin-based products.

Another guidance from the American Society of Hematology (ASH) recommended prophylactic LMWH doses for all hospitalized COVID-19 patients. This is “despite abnormal coagulation tests in the absence of active bleeding, and held only if platelet counts are less than 25 x 109/L, or fibrinogen less than 0.5 g/L,” ASH indicated.

In patients with COVID-19-associated coagulopathy/DIC, the group said it wasn’t necessary to administer therapeutic anticoagulation, unless there was some documentation of venous thromboembolism (VTE) or atrial fibrillation. For patients already on such therapy for VTE or atrial fibrillation, “therapeutic doses of anticoagulant therapy should continue but may need to be held if the platelet count is less than 30-50 x 109/L or if the fibrinogen is less than 1.0 g/L,” the group stated. To balance risk of bleeding and thrombosis, clinicians should assess patients on an individual basis.

Two other documents, one by ISTH, another by a triumvirate of physicians, weighed in on COVID-19 and coagulopathy tests and treatments. In its interim guidance, ISTH recommended four lab tests to help determine prognosis in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: D-dimer, prothrombin time, platelet count and fibrinogen. The other guidance, the Hunt-Retter-McClintock (HRM) document, mostly agreed with ISTH’s recommendations, except for some minor points on patient care. ISTH recommended keeping platelet counts in non-bleeding patients with coagulopathy above 20 x 109/L and fibrinogen above 2.0 g/L.

Comparatively, authors of the HRM document did not think correction was necessary in non-bleeding patients with abnormal coagulation test results, Stephan Moll, MD, professor in the Department of Medicine and Division of Hematology-Oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, wrote in a blog post. In patients experiencing major bleeding, “the ISTH document recommends that fibrinogen is to be kept above 2.0 g/L, whereas the HRM document recommends that it be kept above 1.5 g/dL,” Moll explained.