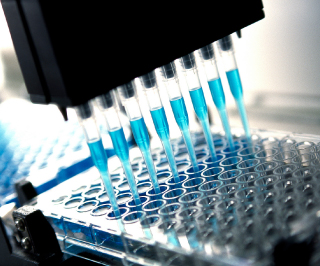

Image credit: iStock.com/DavidBGray

Researchers were able to successfully harness an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect autoantibodies in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a method that could pave the way for a quicker, more efficient way to diagnose this elusive condition.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ 26th Annual Scientific & Clinical Congress in Austin, Texas, featured a late-breaking abstract (1125) on the study’s results, which suggest that PCOS may be an autoimmune disorder.

PCOS affects 8%-10% of reproductive-age women, who typically present with polycystic ovaries, androgen excess, and ovulatory problems. As the authors explain in their abstract, its etiology is unclear, and there’s no definitive test that identifies PCOS.

PCOS is difficult to diagnose and treat, David Kem, MD, a professor at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center’s endocrinology and diabetes section and an author of the paper, told CLN Stat. Right now, clinicians diagnose this syndrome by exclusion under so-called Rotterdam criteria. Patients essentially have to meet two of three criteria: infertility; evidence for cysts in the ovaries (difficult to detect via pelvic exam so may necessitate an expensive ultrasound), and evidence for increased androgen activity. These are often indistinct observations, and definitive diagnosis typically takes years.

“There seems to be a spectrum of clinical signs, which may make it more difficult to identify by physicians who don’t specialize in PCOS. It is often discussed that there is a delay in diagnosis,” Gregory Dodell, MD, FACE, assistant clinical professor of medicine, endocrinology, diabetes, and bone disease at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, told CLN Stat.

If an antibody test to identify PCOS existed, more women with PCOS symptoms would be diagnosed and treated at earlier stages—which could substantially improve their overall health and quality of life, offered Dodell, who was not involved in the study.

Researchers to date have not been able to identify an autoimmune link to PCOS. However, in this particular abstract, investigators acted on a hypothesis that activating autoantibodies directed to the second extracellular loop (ECL2) of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GnRHR) were present in PCOS.

Kem and his colleagues’ research involving PCOS was informed by their previous work that had identified likely autoimmune causes for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a disease that occurs in women and may present less frequently in men or boys.

“We’d noticed that several female patients with POTS had autoantibodies that activate specific receptors called G-protein coupled receptors,” he said. Although that particular body of research focused on the cardiovascular system, the investigators noticed that several patients with POTS also had PCOS.

“It dawned on me that this type of autoantibody might also be present in PCOS patients, and the likely target for that would be receptors in the pituitary gland. We noticed in the course of our work that the autoantibodies connected to these receptors were using the second extracellular loop—a part of the receptor that sticks out from the cell wall into the serum,” he explained.

The investigators synthesized the 28 AA GnRHR ECL2 loop they suspected would be a likely target for PCOS, to create an ELISA assay. The next step was to analyze serum of 32 PCOS patients and 38 age- and body-mass-index-matched, ovulatory infertile women who were not found to have PCOS by the usual criteria.

“We found that a very high percentage of our patients had antibodies via ELISA to this particular 28 amino acid segment,” Kem said.

Compared with subjects with tubal factor, male factor, or unexplained infertility, “we found a significant increase in the developed ELISA optical density in subjects with PCOS,” according to the abstract.

The ELISA assay yielded a 91% and 87% sensitivity and specificity for PCOS, respectively.

“The present assay, with validation from our ongoing activity and blocking studies, may represent the desired serological test needed to effectively screen subjects for possible PCOS. This is the first assay that appears to satisfy the criteria needed for screening and evaluating such patients,” the investigators concluded.

While the ELISA assay looks promising as a diagnostic tool, Kem said it won’t be ready for clinical use until it goes through further validation and additional improvements. “Any assay has to go through detailed testing to be CLIA-approved,” he said. For now, “we’re reassured this antibody exists and this assay, once developed, has potential for clinical usage.”