Image credit: ollaweila/Thinkstock

Image credit: ollaweila/Thinkstock

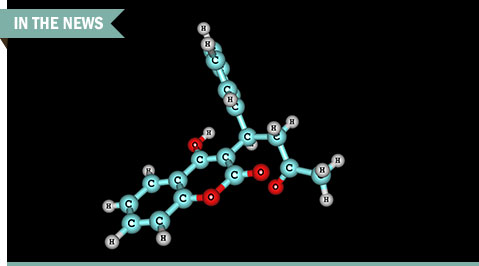

Two genotypes helped identify patients who not only were more likely to experience early bleeding while taking the popular anticoagulant warfarin, but also more likely to safely take the newer anticoagulant edoxaban instead of warfarin, finds a new study, published in The Lancet.

It’s well known that serious bleeding complications are common with warfarin, but demonstrating in clinical trials that doses adjusted according to certain genetic polymorphisms results in fewer adverse events has proved elusive. However, the new research has clarified the role of pharmacogenetic testing in anticoagulant dosing.

"We were able to look at patients from around the world who were being treated with warfarin and found that certain genetic variants make a difference for an individual's risk for bleeding," Jessica L. Mega, MD, MPH, lead author of the paper, said in a prepared statement. "For these patients who are sensitive or highly sensitive responders based on genetics, we observed a higher risk of bleeding in the first several months with warfarin, and consequently, a big reduction in bleeding when treated with the drug edoxaban instead of warfarin."

The randomized, double-blind clinical trial included 14,348 patients with atrial fibrillation who were assigned to take warfarin or a high- or low-dose version of edoxaban once per day. A subgroup of participants underwent genetic analysis and were then categorized into “genotype function bins”—normal, sensitive, or highly sensitive in their responses to warfarin. Of 4,833 study participants taking warfarin, 2,982 people were determined to be normal responders, 1,711 were sensitive responders, and 140 were highly sensitive responders. “Compared with normal responders, sensitive and highly sensitive responders spent greater proportions of time over-anticoagulated in the first 90 days of treatment … and had increased risks of bleeding with warfarin,” according to the study.

In the first 90 days of the study, edoxaban treatment reduced bleeding more in sensitive and highly sensitive responders than in normal responders, when compared with warfarin. After 90 days, the bleeding risk reduction between the two drugs was similar across genotypes. As such, the study authors concluded that “CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes identify patients who are more likely to experience early bleeding with warfarin and who derive a greater early safety benefit from edoxaban compared with warfarin.”

In commentary accompanying the new research, Alan Wu, PhD, DABCC, of San Francisco General Hospital and the University of California, San Francisco, wrote that the new information suggests that pharmacogenomic testing could be used in patients with atrial fibrillation to “optimize choice of treatment.” Edoxaban and other novel anticoagulants “could be reserved for individuals who are classified as sensitive or highly sensitive responders,” Wu explained.

Still more research is needed before changing medical practice. “This concept must be tested in a prospective trial where participants who are determined to be sensitive or highly sensitive to warfarin are randomised to either warfarin or one of the newer drugs,” Wu wrote. “If the incidence of bleeding does not differ, warfarin can continue to be used as an inexpensive alternative, especially while the novel anticoagulants are on patent. Unfortunately, further warfarin pharmacogenomics trials are unlikely to be funded because the drug is off patent and the results would not benefit pharmaceutical manufacturers.”