Molecular testing has been launched into the stratosphere because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical laboratories around the world have invested billions of dollars not only in test kits for SARS-CoV-2, but in new instruments, staff, and other resources to support the enormous volume of testing required.

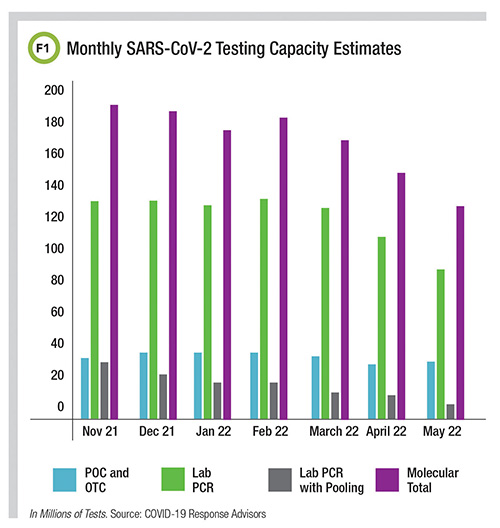

According to COVID-19 Response Advisors, monthly capacity for molecular SARS-CoV-2 testing in the U.S. was estimated to be 128 million in May 2022, although about a quarter of that includes point-of-care and over-the-counter molecular systems (Figure 1).

The new focus on molecular capability also has spurred innovation, as laboratorians determine what other areas could benefit from a molecular testing capacity boost, while also figuring out what to do with instruments bought to satisfy the demands of peak pandemic testing.

CLN talked to Esther Babady, PhD, chief of clinical microbiology service at Memorial Sloan Kettering about what she sees.

The pandemic has put so much emphasis on developing PCR testing. How will this change the types of tests and instruments clinical laboratories consider going forward?

The pandemic has brought knowledge of advanced, high complexity testing into everyday life. Now people outside medicine talk about PCR testing like it’s something everyone should understand.

This awareness has opened up a future for performing more testing, particularly infectious disease testing, at home. Before the pandemic, it would have blown my mind that in some cases molecular testing would be simplified to the point that a layperson could do it at home. This new reality is going to create a new set of challenges, but that door is now open, and we have to figure out how we walk through it.

What kinds of challenges do you mean?

The demand for SARS-CoV-2 tests has shown some of the limitations with molecular testing. One of the most controversial discussions around COVID-19 and molecular testing is cycle threshold, or CT, value and being able to understand viral load. CT values aim to capture information not only about how much virus is present in a sample but sometimes to infer how infectious a person might be.

And the issue becomes that just detecting nucleic acids is not going to be enough to make at-home molecular tests as useful as we might want them to be. We need to figure out which molecular marker—or something else—will identify when a person is actually infectious.

In the pandemic, we discovered both the promise and the limitations of current PCR testing: We figured out that we can make things simple and reliable enough for patients to perform them at home, but now we’re left with questions on how to make things a bit more advanced in order to capture the information we really want about who is infectious and who is not.

What are some smart ways that laboratories can use built-up capacity for SARS-CoV-2 testing after the pandemic recedes?

At the beginning of the pandemic, when we were all looking for platforms for testing, I had in the back of my mind, “What are we going to do once we don’t need all of these?” Well, with continuing waves of the virus, we still need all these instruments right now. But it’s still the case that we’ll have all this new capacity for molecular testing. The question is: what else can you do?

Perhaps now there is more incentive for manufacturers to develop IVD assays that labs can use on these platforms. It’s something that will take time to move through the FDA process. Meanwhile, for laboratories that have acquired these platforms, developing tests in-house that traditionally they were sending out to reference laboratories is one option.

Laboratories are all different. They are going to have to be creative to make sure this instrumentation is still beneficial and properly used. I think it’s positive that this opens up new discussions about bringing new tests to hospitals’ in-house laboratories, as well as laboratories themselves becoming more molecular-focused.

Yet, we know that this pandemic is so unpredictable. One minute we have low case counts and think we can move on to other things. And then, boom, another wave. For now, we’re certainly not getting rid of any of these instruments.

How did the experience with molecular testing during the pandemic change the way laboratories are thinking about automation?

I think this also goes back to the question of, now that we have all these platforms, what are laboratories going to do with them? We hadn’t planned to automate as much in microbiology, where we had only a few assays that ran on some of the automated platforms. We performed a lot of laboratory-developed tests that had been very manual.

With the pandemic, that became such a challenge, because we didn’t have the front-end automation—beyond just automating the extraction and PCR—that was much more common in the clinical chemistry laboratory. It introduced a new element for us when we think about molecular testing and automation.

How can this experience offer ways for labs to improve patient care in the future with molecular testing?

One of the ways this is going to improve patient care is related to the fact that we now have molecular at-home testing, which means that we can make it faster in clinical point-of-care settings, too.

Molecular tests used to require a 24−48-hour turnaround time. Then manufacturers came out with rapid moderately complex testing platforms for the laboratory with a 1−3 hour turnaround, depending on the test.

During the pandemic, we’ve taken the leap to frequent use of point-of-care molecular testing, even in clinics or for patients presenting in the emergency department. I expect we’re going to be seeing a lot more tests on the menu of point-of-care molecular platforms. They’re more sensitive than antigen tests, and point-of-care testing avoids sending some of the more routine testing back to the laboratory.

This would improve patient care just because the clinician and the patient get an answer much more quickly.

Where specifically do you think these improvements are going to be?

Before COVID-19, we had already started to see a couple of assays that focused on flu and respiratory syncytial virus. We had antigen tests, but they’re not necessarily the most sensitive. Same for streptococcal pharyngitis. Now a PCR assay can be performed in the emergency department on the same platforms on which SARS-CoV-2 tests were developed.

FDA has also approved molecular tests for some sexually transmitted diseases, so patients can test themselves from the comfort of their homes.

Do you see any other changes to how PCR tests will be used from now on?

Until COVID-19, medicine was not as focused on how a virus changes, or how pathogens evolve. We’ve now learned that we need to improve how we monitor variants and mutations. Even with flu, we are essentially offering a yes/no answer, only adding whether the patient has influenza A or influenza B, or maybe particular genotype. However, we know that the flu virus develops mutations that make it resistant to antiviral therapy.

We need better tools to monitor mutations for pathogens other than SARS-CoV-2—and to be able to act on that information quickly. That means having tools to perform genotyping more readily for other respiratory viruses that are circulating.

Jen A. Miller is a freelance journalist who lives in Audubon, New Jersey. @byJenAMiller