Laboratory stewardship is not for the faint of heart. Performing this vital function demands considerable energy in fighting the constant, uphill battle against a small portion of the lab industry that enthusiastically markets new, proprietary tests with potentially exaggerated claims. This marketing is usually directed toward labs and sometimes to patients and families, either directly or through information on a website. While some of these tests are clinically useful, many lack clinical utility.

The difficulty in adjudicating these requests arises in that often they are marketed for clinical conditions which involve profound patient suffering. The psychosocial nature of wanting to understand more in the face of suffering is universal and understandable. This leads to tremendous pressures on care providers when patients directly request these tests.

In response to such test requests, laboratorians must perform challenging assessments about whether a test provides evidence-based clinical utility. This article will walk through a framework for handling these requests, using a composite teaching case that involves a commercial antibody panel. We have derived this de-identified case not only from our own experience but also that of several members of our Patient-Centered Laboratory Utilization Guidance Service (PLUGS).

Case Study: A Questionable Commercial Antibody Panel

A single commercial laboratory has developed and marketed an antibody panel as a diagnostic test for pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcus (PANDAS). These disorders have similar proposed diagnostic criteria that include sudden onset of behavior changes, at least two qualifying behavior attributes, and lack of known medical or neurologic disorders. The main difference between the two conditions is that PANDAS includes tics as a possible primary symptom as well as a confirmed streptococcal infection before symptom onset.

The promise of new treatments targeted to autoimmune conditions, such as intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, makes diagnosis with biomarkers appealing. The panel from the commercial lab includes autoantibodies to dopamine receptors in which a positive result could justify treatment. In this case study, the lab receives a request from a psychiatrist to evaluate this testing at the request of a family who found the test online.

The Laboratory’s Response

The dilemma presented in this case study demands a threefold approach: Do homework, provide support to the care provider who received the request, and make a policy and procedure that helps deal with the next request for the same panel.

Do the Homework

In this case, as with all laboratory stewardship interventions, due diligence will carry the day in understanding the current state of the test in question. A thorough literature search can provide meaningful information. Signs suggesting that a test might lack clinical utility include (from least to most concerning):

- The test does not appear in a diagnostic guideline offered from a reputable society or policymaking body.

- No peer-reviewed studies exist from independent sources indicating the test’s clinical utility.

- The only peer-reviewed publication on the test’s clinical utility comes from the commercial lab offering the test.

- No peer-reviewed publications exist on this test.

- Choosing Wisely (www.choosingwisely.org) specifically notes that the test lacks clinical utility.

- The test appears on Quackwatch (www.quackwatch.org).

In addition to these signs, it is useful to determine whether other laboratories offer similar tests. While a clinically useful, cutting-edge test occasionally will be offered by only one laboratory, much more commonly a clinically useful test will be developed and offered by several major reference laboratories and elite academic medical centers.

In our example of the autoantibody panel for PANS/PANDAS, the literature painted an unusual and controversial landscape. Only one study independently evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of the autoantibody panel (1), and this study directly conflicted with a study authored by the inventors of the commercial panel (2). The independent study found that the control patients had a similar test positivity rate (86%) to the patients assessed for PANS/PANDAS (92%). Thus, the authors concluded that since “none of the individual scores or any composite score corresponded with a diagnostic odds ratio >1,” the commercial autoantibody panel was no better than chance in detecting PANS or PANDAS. Additionally, no other clinical lab could be found offering any of the autoantibodies in the panel.

Provide Support

Families often take the information they gather about proprietary tests to their care providers and direct the providers to order and coordinate testing. This is known as “patient-directed” testing, and nearly half of care providers encounter these requests in their practice. Providers are often unfamiliar with the test in question and feel pressured to complete the request to maintain a good patient-doctor relationship.

Laboratory stewardship programs can help these providers move from patient-directed testing to patient-centered testing. The latter involves testing that has a reasonable evidence base for clinical utility and is the right test for a patient.

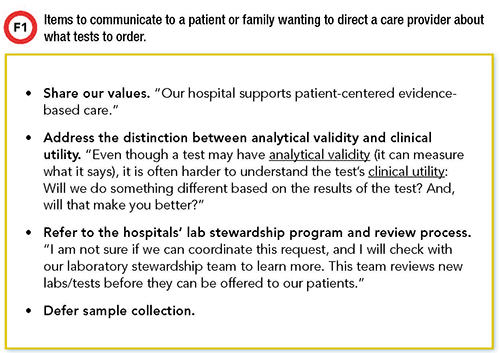

In this case study, the psychiatrist reached out to the laboratory stewardship team to ask about the clinical utility of the autoantibody panel. The lab stewardship team shared with the practitioner the facts from their literature and guideline review and then strategized how to communicate with the family (See Figure 1).

The lab stewardship team also offered to step in and speak with the patient if the provider felt uncomfortable communicating this information. Often, laboratory stewardship involves replacing well-meaning, but inappropriate, test requests with appropriate testing. However, in this case no test was the best test.

Make a Policy and Procedure for Future Requests

Once a decision has been made not to use a certain laboratory or laboratory test, this decision should be put into practice through a policy and procedure that supports providers the next time a patient requests the test.

In our case study, the clinical lab incorporated a policy to ban the commercial autoantibody panel and added the panel to the list of tests which have limited or no clinical utility. The lab links to this list in its online test catalog. As part of the lab’s procedures around banning a particular test, the lab stewardship team also will offer to explain to the patient-facing provider why the test is banned so that this provider will be better able to communicate to the patient or family. In addition to the list of tests with limited or no value—available to anyone who searches the lab’s test catalog—the policy and procedure links to test-specific pages that include instructions for phlebotomists or providers who may find themselves in front of a patient requesting the test.

After the lab published the information about our case study autoantibody panel in its online test catalog, the stewardship team heard from a different physician, not in psychiatry, that this information helped evaluate a request in their clinic, preventing patient-directed testing of no clinical utility. The patient in this case was grateful for the information and happy to not have testing.

Conclusions

The moral of this story is that due to skilled and sometimes aggressive test marketing, laboratorians who are serious about stewardship need to prepare for difficult discussions with providers and with patients about tests that lack clinical utility. Having a well-considered plan for how to respond will help clinical laboratorians stay one step ahead of such requests and ensure that patients get only the right tests at the right time.

Jane Dickerson, PhD, DABCC, is clinical associate professor at the University of Washington and director for clinical chemistry at Seattle Children’s Hospital in Seattle. +Email: [email protected]

Michael Astion, MD, PhD, is clinical professor of laboratory medicine at the University of Washington department of laboratory medicine and medical director of the department of laboratories at Seattle Children’s Hospital. +Email: [email protected]

REFERENCES

- Hesselmark E, Bejerot S. Biomarkers for diagnosis of pediatric acute neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) - Sensitivity and specificity of the Cunningham Panel. J Neuroimmunol 2017;312:31–7

- Singer HS, Mascaro-Blanco A, Alvarez K, et al. Neuronal antibody biomarkers for Sydenham’s chorea identify a new group of children with chronic recurrent episodic acute exacerbations of tic and obsessive compulsive symptoms following a streptococcal infection. PLoS One 2015;10:e0120499.