State newborn screening programs without question are one of the most successful public health initiatives of modern times. From the first newborn screening test for phenylketonuria to be adopted widely in the 1960s, the number of tests included in the nationally recommended uniform screening panel (RUSP) has grown steadily to 34, with some states screening for as many as 58 conditions.

Today, nearly every baby born in the United States—about 4 million each year—receives vital screening, with around 12,000 identified as having a serious disease. “Newborn screening programs provide universal access for all U.S. newborns to services that can be life-changing and even life-saving,” said Carla Cuthbert, PhD, FACMG, FCCMG, chief of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Newborn Screening and Molecular Biology Branch.

Despite this overall remarkable track record, newborn screening is not a perfect system. States have different procedures for how babies’ blood gets collected and transported from hospitals to state labs, different testing methods and turnaround times, and different approaches for interpreting results, including setting cutoffs. These differences, already on the radar screen of public health stakeholders, were brought into sharp focus via a series of media reports.

Delays and Differences

In 2013, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel found wide variations in how quickly samples made it to and were processed by state labs. These delays had profound consequences for some babies, including two who were profiled in the series.The Journal Sentinel revisited newborn screening in December 2016, finding wide variability among states in setting reference ranges and in communicating test results.

One article focused in part on the legal proceedings of a case involving a child belatedly diagnosed with propionic acidemia. His initial newborn screening result came back “possible abnormal,” and the lab recommended collecting another sample. The second result, reported as “normal,” showed the actual test values and commented that the C3/C2 (propionylcarnitine/acetylcarnitine) ratio was elevated, but did not make follow-up recommendations.

The Journal Sentinel reported that in evaluating what went wrong, a Wisconsin advisory committee determined that in comparison to other states, Wisconsin’s program used a much higher cutoff for one marker, while the other was in line with most states. “A child’s life-threatening condition might be caught in one state but missed in another because there’s little uniformity in the policies, procedures, and cutoffs used to screen disorders,” wrote investigative reporter Ellen Gabler.

She acknowledged the balancing act states have in considering time, money, and science when establishing condition-specific cutoffs. Higher thresholds lessen the risk of missing true positive cases, but setting a cutoff too low also causes problems. If too many false-positives turn up, limited resources are wasted on follow-up testing for infants who aren’t truly sick, while raising families’ anxieties. States also have to make adjustments to account for genetic risks specific to their populations, such as the Amish community in Wisconsin and Native Alaskans in that state.

Guidance on Best Practices

Even before these revelations, efforts were underway to improve newborn screening nation-wide, and states have been steadily working on speeding the overall newborn screening process. “State labs are taking it really seriously,” said Paul Jarris, MD, MBA, chief medical officer of the March of Dimes, which funds research for problems that threaten the health of babies and advocates for improving maternal and infant health. “They’ve taken it on as a quality assessment initiative.”

A report documenting continued improvements will be presented at the November meeting of the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC), said Guisou Zarbalian, a senior specialist of newborn screening and genetics at the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL). “Public health labs are doing a tremendous job in the face of these challenges,” he said.

Indeed, both the logistics of screening and issues around setting cutoffs have been on ACHDNC’s radar screen. ACHDNC not only recommends changes to the RUSP but also advises the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on newborn screening tests, technologies, policies, guidelines, and standards. A draft guidance document on determining cutoffs was presented to ACHDNC at its August meeting and is winding its way toward anticipated publication in November.

The guidance document is being developed by APHL’s Newborn Screening Quality Assurance/Quality Control Subcommittee, under the auspices of ACHDNC’s Laboratory Standards and Procedures Workgroup. In an overview presented at ACHDNC’s August meeting workgroup co-chair, Kellie Kelm, PhD, deputy director of the division of chemistry and toxicology devices at the Food and Drug Administration, indicated that the idea behind the document is to “be able to point people to resources of some of the approaches newborn screening programs may take in determining between normal and abnormal test results.”

In addition to providing an overview of typical procedures for determining a cutoff, the document is expected to discuss setting cutoffs for specific disease categories like amino acid disorders, and to describe approaches for challenging a preliminary cutoff such as running known positives from other states. The paper also is expected to review special considerations such as how babies’ age at screening and birth weight might affect results, and to explore how states evaluate and monitor cutoffs.

Current Cutoff Practices

Independent of the guidance document, APHL and its Committee on Newborn Screening and Genetics in Public Health from May through July 2017 surveyed 53 state and territory screening programs on their cutoff procedures and use of analytical tools. Preliminary results reflecting responses from 38 programs also were presented at ACHDNC’s August meeting.

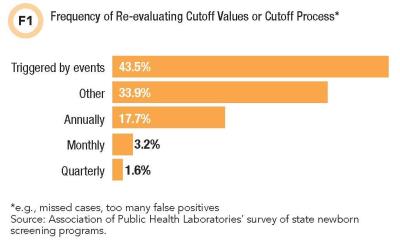

A solid 43.5% of respondents reported re-evaluating their cutoffs or process for determining cutoffs in response to events like missing a case or discovering that the program is reporting too many false positive results (see Figure 1). A minority seemed to reassess only on a set schedule.

Participants reported using a variety of approaches for establishing cutoffs, including using vendor recommendations from kit inserts, analyzing state population data based on screening results from normal and affected babies, incorporating feedback from specialists, and consulting other newborn screening programs, published literature, or tools like R4S and CLIR.

Mayo Clinic developed and maintains both R4S, a web-based database tool and pattern recognition software freely available for laboratories to report and analyze newborn screening results, and CLIR—Collaborative Laboratory Integrated Reports—a richer version of R4S that adjusts results for variables like age, birth weight, and sex. Rather than characterize a screening result strictly in terms of deviations from normal, R4S and CLIR analyze how the result fits within a disease range for a particular condition based on an extensive database of true positive cases.

R4S and CLIR may represent the future in setting cutoffs and interpreting test results, but adopting these new approaches does not appear to be a slam-dunk. In the APHL survey, most programs reported using them regularly for activities like determining what to include in their risk assessments and in managing cutoffs. However the survey reflected some skepticism and even some misunderstanding about them.

“Not enough evidence that [they] work better than cut-offs to convince us to do so,” wrote one respondent. “The tool risk determination continuously evolves every time someone is adding data.”

Responses such as this provoked discussion during the ACHDNC meeting on the need for both provider and public education about the newborn screening process, including tools like R4S and CLIR. For example, a retrospective review of more than 176,000 cases in California analyzing R4S in comparison to actual screening results showed that R4S would have reduced false-positives by 90% (Genet Med 2014;16:889–95).

Nearly one-third of respondents also indicated that they used to submit normal population or case data to R4S or CLIR but no longer do so, citing staff resource constraints and concerns about data security and parental consent issues.

Standardized National Cutoffs?

One ACHDNC member characterized a “desperate need” for cutoff standardization and asked what the barriers are to creating national thresholds. Cuthbert explained the impracticalities of such an approach. “At one level, it would be nice to have a single cutoff and have every state conform to it. That’s just not how it happens in practice in laboratories,” she said.

Cuthbert went on to emphasize CDC’s interest in building on its existing newborn screening quality assurance services to help programs in determining and managing their cutoffs. She floated an idea preliminarily being discussed involving the agency receiving borderline positive cases from state programs, retesting them, and creating and distributing new quality assurance materials¬ that mimic these borderline samples to help states evaluate their performance.

These and other insights may surface as the guidance document is finalized and APHL and ACHDNC continue to absorb the survey findings, with the common goal of improving the newborn screening process. “Any time you lose a child from one of these disorders, it’s a preventable death,” Jarris said. “Our tolerance for that should be zero.”

Rina Shaikh-Lesko is a freelance science writer in San Jose, California. +Email: [email protected]