Many hospitals have embarked on patient safety programs using as a foundation the five principles of high-reliability organizations (HROs). These five principles include sensitivity to operations, commitment to resilience, reluctance to simplify explanations of successes and failures, preoccupation with failure, and deference to expertise.

According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a defining characteristic of HROs is an appreciation that “the people closest to the work are the most knowledgeable about the work.” This means that in an emergency, the person with the highest seniority might not be the most knowledgeable about the situation. In addition, AHRQ notes that deference to this local and situational expertise in HROs “results in a spirit of inquiry and de-emphasis on hierarchy in favor of learning as much as possible about potential safety threats.” This makes staff comfortable speaking up when they see a safety problem.

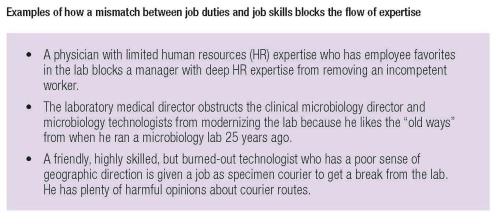

However, fostering deference to expertise is not easy and sometimes presents unexpected and thorny problems for clinical laboratories—not only in emergencies but also in daily operations and essential quality improvement (QI) programs.

Deference to Expertise in Daily Operations

Expertise needs to flow without obstruction to the sharp end of operations, where staff handle specimens and perform tests. In daily operations, organizations with deference to expertise focus on ensuring staff fit their jobs, have training for the tasks they perform, receive continuing education, and acquire training in improvement methods. These staff-affirming concepts are simple in principle but challenging in practice. For example, consider the case of a newly hired technologist. He excels at developing new tests and troubleshooting instruments, but is also impatient, a bad listener, and has limited knowledge of processes outside technical areas. If management assigns him to the client services center to handle doctors’ and nurses’ phone calls, this talented but misfit technologist will obstruct the expertise of the other members of the client services team.

Deference to Expertise in an Emergency

The more emergent a situation is, the greater the need for experts to resolve it. For example, when a core lab instrument goes down unexpectedly, guidance by front-line workers and supervisors is a must. These frontline workers have faced the problem before and know the nuances of the key policies, procedures, and relationships. They also know where the best backup is located, whom to call to fix the primary instrument, and which units and care providers are most at risk for delays. All of this knowledge helps them mitigate core lab downtime.

With a core lab instrument down, deferring to hierarchy rather than to front-line workers’ expertise would be a big mistake. The lab does not need a highly ranked and friendly pathologist without experience in this domain to find a resolution to this emergency. The ability to overcome this hierarchy in emergencies, where rapid decisions have to be made at the sharp end of work, is an important characteristic of HROs.

A reasonable guideline for leaders is that the more emergent the situation, the more the higher-ups in the organization should migrate toward removing obstacles and greasing wheels and away from coaching the immediate work. A colleague of mine relayed an example of this approach in action. During an unusual snow emergency in this person’s normally fair-weather city, the lab faced an unprecedented problem: getting staff into work. Two groups of senior leaders each took different approaches, but only one turned out to be helpful.

The first group of leaders, who had rarely been in the lab, offered all kinds of well-meaning but ultimately useless advice and directions. In this case, front-line workers and supervisors saved the day by identifying colleagues who lived close by and could get to work and stay there for long hours. They also found staff from specialty labs with less stringent turnaround time requirements who were cross-trained in the core lab and could run urgently needed testing.

In contrast, a different senior leader stepped in to remove obstacles and facilitate the flow of expertise by using his own 4-wheel drive vehicle to transport lab workers from their homes. This was a triumph of humility and utility over hierarchy. Another senior leader made hotel reservations nearby for the lab staff who would be working in town for a few days. Yet another bought pizza and put it in the break room next to the lab since any breaks were going to be short and infrequent. Another walked around—without interrupting—and thanked people for getting in and told them how much their dedication meant to patients and care providers.

Deference to Expertise in Quality Improvement

QI presents the most unique challenges for HROs. Whereas daily operations necessitate that expertise be unobstructed in the moment, and emergencies require the big dogs to step back, QI usually is not emergent. This is the ideal setup for expertise to be stifled.

In labs, three kinds of problems commonly block expertise in QI: overuse of inexperienced outside consultants, victimization by QI governance, and obstruction by

prima donnas.

Some consultants are true experts who help improve quality. This is especially so if they have accomplished a difficult QI project, such as total lab automation or 24-hour phlebotomy services.

Unfortunately many consultants foisted on labs are not experts. They either worked in labs eons ago, or sometimes never have. These advisers are sold as general experts in a disciplined problem-solving method like lean, but in fact, they are lean-educated travelers whose primary expertise is in the presentation arts, delivering lectures developed by actual expert consultants. These travelers often are charming, well-dressed, and well-meaning, but they have little operational expertise.

Labs might deal with such inexperienced consultants by respectfully declining their help, or if that is not possible, by educating them so that they represent the lab accurately to upper management, perhaps even advocating for lab experts. I have never met an inexperienced consultant who wanted to do a bad job—although I have met a few with confidence that did not match their competence in operations. In my view it’s worth labs’ time to educate this particular breed of consultants and then affirm them if they advocate for decisions that allow lab expertise to flow.

The second common QI problem labs face is victimization by governance. In these situations, an organizational QI hierarchy is so dense and opaque that there is no way to reasonably traverse it. Ineffective governance often manifests as the need for multiple levels and unclear lines of approval, inability to generate decision rights, and endless committee and subcommittee meetings. As a result of these roadblocks, only the simplest QI projects move forward and experts don’t have the leeway to innovate, especially if a purchase is required—even one with a solid return on investment.

The third challenge, the prima donna syndrome, is a fascinating and all too common phenomenon in which experts within the organization block their colleagues’ expertise. Prima donnas achieve formal or informal power through specialized expertise and technical prowess. They tend to be confident, loud, demanding, and difficult to manage.

Prima donnas pose several problems in QI. They tend to restrict or silence the voices of other experts and to improperly prioritize their work above other lab sections. While the prima donna syndrome presents management challenges, effective strategies to guide these individuals include: 1) making QI conversations about expertise, not experts, 2) reminding staff that lab expertise at the sharp end is a symphony requiring many different kinds of expertise, 3) specifically seeking input from all experts without favoring the prima donnas, and 4) coaching the prima donnas, always aiming them toward reality. Emphasize that they are not the only experts and don’t know everything. Their expertise is important, but is made much better by including the entire group.

These problems with deference to expertise and QI arise at some point in most healthcare organizations. No leadership group sets out to overuse inexperienced consultants, create unworkable governance, and enable prima donnas. However, identifying these problems is the first step to dismantling them. Understanding some of the pitfalls to avoid when attempting to achieve this goal is a good place to start on the road to deference.

Michael Astion, MD, PhD, is clinical professor of laboratory medicine at the University of Washington department of laboratory medicine, and medical director of the department of laboratories, Seattle Children’s Hospital. +Email: [email protected]

References

High Reliability, Patient Safety Primer. July 2016. Available at: http://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/31/high-reliability. Accessed May 9, 2017.

Dekker SW. Deferring to expertise vs the prima donna syndrome: a manager’s dilemma. Cogn Tech Work 2014; 16:541–8.

The inability of people to recognize their own incompetence: An interview with Dr. David Davis. Clinical Laboratory News 2008;34(10):20–1.

CLN's Patient Safety Focus is sponsored by ARUP Laboratories