As part of their accreditation, clinical laboratories are required to have plans in place to respond to natural disasters and other emergency events. However, getting these plans on paper is not the same thing as practicing, analyzing, and improving them. Moreover, laboratories must be sure not to neglect internal threats such as a fire, chemical spill, or other emergencies even as they focus on larger-scale disasters like hurricanes or tornadoes.

One way to approach emergency planning that incorporates documentation, planning, and practice is the Six Sigma methodology. The goal of the Six Sigma methodology is implementing a measurement-based strategy that focuses on process improvement and variation reduction through the application of Six Sigma improvement projects (See Suggested Reading). Often applied to improve efficiency, productivity, and quality within a clinical laboratory, a Six Sigma project can be employed to focus on other areas, including emergency preparedness.

As part of a safety initiative within Mayo Clinic’s Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, we formed a project team to review our current safety practices. In June 2013, this nine-person team, led by our systems engineer, Fazi Amirahmadi, PhD, began work to develop safety processes. This included educating all staff on appropriate actions during emergencies that required relocation or evacuation. Our work environment consists of approximately 148 people who have workspaces on the 11th floor of the Mayo Clinic’s Hilton Building in Rochester, Minnesota. This includes physicians, fellows, residents, and support staff who work in walled offices, cubicals, and shared workspaces.

We successfully used the Six Sigma Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control (DMAIC) problem-solving methodology to manage and improve our existing Emergency Preparedness Plan (EPP). We feel that our situation is not unique and our hope is that other labs and work units will benefit from the methodology

we used.

Define the Problem

The first phase includes defining the problem, setting goals, and establishing a timeline for the project. We investigated the existing emergency preparedness for our floor by identifying gaps in our documentation, visual tools, and our staff’s knowledge of emergency readiness. Our goal was to improve all identified gaps by at least 10% by the end of 2014. To help us identify specific gaps, we surveyed the staff, and 117 (79%) responded to the survey.

Measure

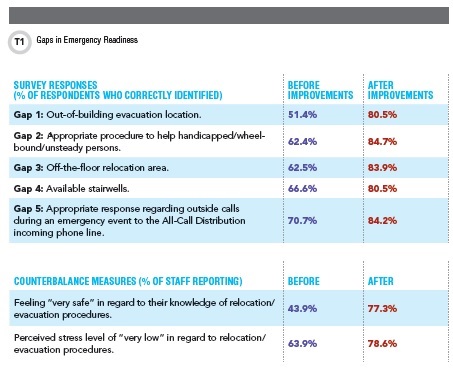

The second phase was to measure our current state as a benchmark for comparison to results following the improvement phase. As a result of our survey, we identified five gaps in our floor’s emergency preparedness by focusing on the questions that had 70% or fewer correct responses.

These gaps included identifying our out-of-building evacuation location (51.4%), knowing the appropriate procedure to help handicapped/wheel-bound/unsteady persons (62.4%), identifying our off-the-floor relocation area (62.5%), being unable to correctly identify the number/location of available stairwells (66.6%), and knowing the appropriate response during an emergency event regarding outside calls to the All-Call Distribution (ACD) incoming phone line (70.7%). The ACD line is a random distribution system for incoming calls to our department. During relocation/evacuation events, an automated message will inform the caller(s) we are experiencing an emergency and ask them to call back in 30 minutes.

We also were able to identify the staff’s perceived feelings of safety (43.9%) and corresponding stress levels (63.9%) as two counterbalance measures for this project. A counterbalance measure is defined as a measure of an attribute of the process that one does not wish to adversely impact while improving the process.

Analyze

The analyze phase calls for using root cause analysis (RCA) to identify the factors contributing to the gaps and develop solutions to eliminate those gaps. We used RCA to recognize major causes for each of the gaps, including an outdated and nonstandard EPP, insufficient orientation and education of staff, absence of visual aids, infrequent drills, and the lack of an ACD emergency message system.

Improve

The fourth phase covers implementing the solutions identified through the analysis, making adjustments as needed, and documenting and standardizing the new process. Based on the root causes we identified, we decided to focus on five interventions to close existing gaps: visual tools, including maps and laminated pocket-sized emergency information calling cards; distributing and labeling rechargeable flashlights; developing a new process for incoming client calls during emergencies; standardizing and updating the EPP manual; and re-educating staff on emergency preparedness and new processes.

To measure the success of our interventions, we reissued the staff survey in July 2014. We had 118 responses to this post-education/post-drill survey (See Table).

Control

The final phase involves identifying the long term process owner and establishing a mechanism to monitor and sustain the gains made over the long term. To control and maintain the improvements we achieved, we formed a three-member safety committee with 6-, 12-, and 18-month initial terms. New members will join for a term of 18 months, thereby assuring continual turnover with experienced members.

The safety committee meets every other month and is responsible for: training new employees according to a recently developed checklist; running annual drills for all staff; performing annual surveys to identify possible new gaps and eliminate them; monitoring and updating EPP as needed; speaking at meetings to provide regular safety updates; managing emergency flashlights and visual tools; keeping the safety bulletin board updated with current safety issues; identifying persons who may be claustrophobic or fearful during stairway travel; and educating staff in appropriate response to panic situations during evacuation.

Lessons Learned

At the start of this project, we felt our floor was prepared for emergency situations. However, the data from the first survey—as well as working through each phase of DMAIC problem-solving—highlighted deficiencies in our emergency preparedness plan. Due to employees’ supportive and collaborative response, we achieved 100% participation in the floor-only relocation and evacuation drills. We believe that regularly sharing safety updates through email, presentations, bulletin boards, and face-to-face communication, was a key factor to our success. We hope that our experience with this process will help other laboratories raise awareness of their overall work unit safety preparedness.

Suggested Reading

- iSixSigma. What is Six Sigma? http://www.isixsigma.com/new-to-six-sigma/getting-started/what-six-sigma (Accessed January 2015).

- iSixSigma. Dictionary, DMAIC. http://www.isixsigma.com/dictionary/dmaic (Accessed January 2015).

- iSixSigma. Sigma performance levels—One to Six Sigma. http://www.isixsigma.com/new-to-six-sigma/sigma-level/sigma-performance-levels-one-six-sigma (Accessed January 2015).

- American Society for Quality. What is Six Sigma? http://asq.org/learn-about-quality/six-sigma/overview/overview.html (Accessed January 2015).

- American Society for Quality. The Define Measure Analyze Improve Control (DMAIC) process. http://asq.org/learn-about-quality/six-sigma/overview/dmaic.html (Accessed January 2015).

Fazi Amirahmadi, PhD, is a systems engineer in the department of laboratory medicine and pathology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

+Email: [email protected]