Sue Garr, BS, MT(ASCP)

Vice President and Division Manager,

Sue Garr, BS, MT(ASCP)

Vice President and Division Manager,

Central Support Services

ARUP Laboratories

Referral testing, commonly called sendouts, is often underappreciated. Sendouts do not involve instrumentation and reagents, so some laboratory managers may think of them as simply a clerical function. Hospital sendout areas are generally small operations staffed by a variety of employees ranging from technicians and phlebotomists to laboratory supervisors. Because most laboratory staff members are concentrating on testing hospital and outreach patients in a timely manner, labs commonly segregate sendout specimens outside the normal laboratory workflow. However, sendout testing is an extremely complex operation, where quality lapses are common and patient care can be seriously impacted. This requires that labs maintain a robust quality management program to cope with a test menu of thousands of different tests, the unique specimen requirements for each of those tests, and the various shipping and information handling processes expected by reference laboratories.

Arguably the biggest patient safety category in referral testing is specimen handling. Specimen integrity is paramount in providing the clinician with a viable laboratory result. This starts with initial collection, which sometimes requires special tubes and/or handling by the phlebotomist, as well as specimen labeling and in some cases clinical information. Specimen handling concludes with packing specimens into shipping containers in such a way that prevents leakage and maintains appropriate temperature.

Laboratorians may not think of sendout testing as particularly time-sensitive because sendouts are not available stat, but timing with these tests is critical for at least two reasons. First, many specimens degrade over time. Ambient specimens are most prone to degradation, but refrigerated specimens can also degrade. This is of particular concern in smaller or rural hospital laboratories, where courier pickups may occur only once a day or less. Even when specimen stability is adequate for initial testing, this may not be the case with all-too-common add-on requests. Due to degraded specimens, add-ons often require either redrawing the patient or running the test with a disclaimer, risking inaccurate results as well as denied reimbursement.

Another example of timing complications is when errors in the referral testing process increase the turnaround time substantially. In contrast to a misdrawn complete blood count, where the local laboratory might be able to redraw the patient and run the test within 1 hour or so, a misdrawn sample that is caught by a referral lab can add days to the turnaround time. Laboratories can avoid this situation by incorporating sendout tests into laboratory information systems (LIS) and interfaces wherever practical. Specimen requirements that are available in the LIS can automatically translate to the collection label and collection list. Tests that are not built into the LIS pose more of a challenge because the laboratorian or phlebotomist has to use either a hard copy of the referral laboratory's user guide or web applications to obtain the collection requirements.

Testing quality can also suffer due to a lack of sendout consolidation. For example, a common, underappreciated error is that laboratories often send out a test that they perform themselves, or in some cases a medically equivalent one. A thorough search of a laboratory's test offerings is advisable before unnecessarily ordering a sendout test. A common cause of sending out in-house tests is that clinicians often order tests that have ambiguous names, confusing sendout staff. Such orders should be clarified first and then vetted by the referral laboratory vendor of choice before being sent out. This strategy not only saves turnaround time, but also cost to the patient.

In other cases, clinicians will specify a test by a proprietary name (e.g., from a particular commercial laboratory), even though a medically equivalent generic test is available locally. Robust laboratory policies can assist with these situations, in the same way that pharmacy policies will allow automatic generic substitution of drugs.

As a national reference lab, ARUP Laboratories receives 16,000 sendout specimens each month and orders from more than 500 laboratory clients. This gives us particular insight into the frequency and consequences of specimen handling problems originating in the sendout areas of local laboratories. In 2013, 13% of specimens our laboratory received were held or canceled for a variety of reasons. Most could have been tested within published turnaround times if the specimens and orders had been placed correctly or had been sent with all the required information.

At ARUP, the most common reasons for delaying or canceling a test include: erroneous information on the test requisition, such as incorrect patient demographic or wrong test selected; incorrect specimens, such as incorrect type, temperature, or pH; and missing or confusing orders, such as duplicate orders, extra specimens, or no test selected. Common errors like these potentially can increase turnaround time from 2 to 20 hours depending on client availability, since the reference lab must contact the client lab for clarification. The turnaround time is sometimes affected even more if patients have to be redrawn.

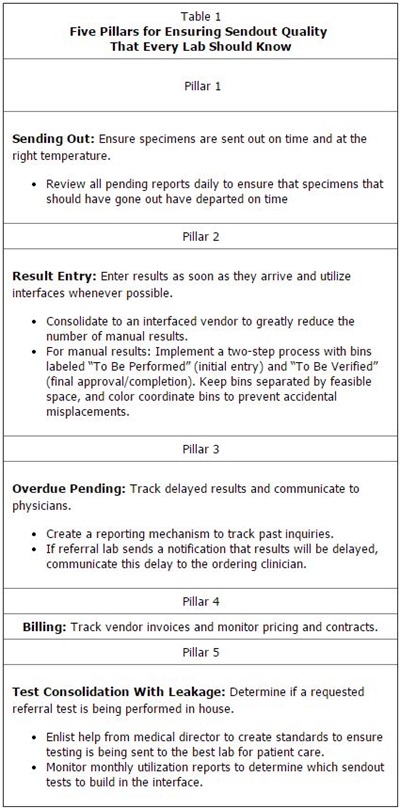

ARUP also maintains a sendouts department for esoteric tests that we do not perform in-house. Table 1 lists the five pillars or principles that our sendouts department applies to their daily tasks. These pillars, along with their associated quality metrics, are the basis of our system to reduce the likelihood of errors in sendouts. They are readily adaptable to clinical laboratories of all sizes.