Warfarin and other vitamin K antagonists have been widely used oral anticoagulant agents for more than 50 years. These drugs are notoriously difficult to dose because of multiple food and drug interactions, very wide variation in the daily doses individual patients require, and the medications' narrow therapeutic index. Patients require careful monitoring via the prothrombin time test, reported as the Internal Normalized Ratio (INR), with the goal of keeping the INR in a therapeutic range, lest patients increase their risk for thrombosis because INR is too low, or develop a greater chance of bleeding because it is too high. Age, weight, and sex influence the effective dose, as do genetic factors.

Research has shown that certain variants in the CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes affect sensitivity to warfarin and similar drugs, suggesting that genetic tests that identify these mutations can help clinicians determine optimal doses of the drug for individual patients. But several small studies on use of these tests, coupled with dosing algorithms that use genetic variants and other factors to determine proper dosing, have had conflicting results.

Three multi-center, randomized, controlled trials published in the December 12 issue of New England Journal of Medicine do little to answer the question of whether pharmacogenomics (PGx) is a significant aid to vitamin K antagonist anticoagulant dosing. While one trial shows that PGx dosing of warfarin is associated with a larger mean percentage of time in the therapeutic range, another says it did not improve coagulation control during the study period and was less effective than traditional dosing methods in African Americans. A third study of two other vitamin K antagonists—acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon—showed PGx testing did not improve the mean percentage of time in the therapeutic INR range overall, but showed some benefit in the first month. All three studies looked for particular variants in CYP2C9 and VKORC1.

"These studies show different results and they add to the confusion about pharmacogenomic dosing for warfarin," said Munir Pirmohamed, PhD, first author of the trial that showed the most promising results for PGx dosing, and chair of the department of molecular and clinical pharmacology at University of Liverpool in England. "More work needs to be done."

Varied Designs and Results

Differences in design, including study size, length, inclusion of different ethnic groups, and other factors may have affected evidence of PGx dosing’s advantages, some study authors said.

Pirmohamed's trial, conducted with other members of European Pharmacogenetics of Anti-coagulant Therapy (EU-PACT), included 455 atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism patients, mostly of European background, from the United Kingdom and Sweden. The patients in this single-blind, multicenter trial were randomly assigned to PGx and control groups, both subject to a loading dosing strategy. The PGx group, which was tested with a point-of-care (POC) device, showed a modest increase in the mean percentage of time in therapeutic range during the first 12 weeks of warfarin therapy. That figure was 67.4% for the PGx patients, compared with 60.3% for controls, a difference of 7.1%. Patients in the genotype-guided group were less likely to have an INR of 4.0 or higher than were those in the control group, and had fewer dose adjustments (N Engl J Med 2013;369:2294–303).

The second study, Clarification of Optimal Anticoagulation Through Genetics (COAG), involved more patients at U.S. sites. With 1,015 patients including African Americans, this double-blind trial followed patients for 3 months, but the authors reported the proportion of time patients remained in range during the first 4 weeks. The mean percentages of time the PGx group and the clinically guided dosing arm remained in the therapeutic range—45.2% and 45.4%, respectively—did not differ significantly. PGx dosing actually produced worse outcomes in African Americans: those who received it had a mean time in range of 32.5%, compared to 43.5% of those in the control group (N Engl J Med 2013;369:2283–93).

The third study involving acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon—commonly prescribed in some European countries—was conducted by other EU-PACT researchers. This trial compared a genotype-based algorithm to a clinically based one, but assessed a primary end point at 12 weeks in two single-blind trials with a combined total of 548 patients who were genotyped with a POC device. While COAG used standardized dose-adjustment methods, the second EU-PACT trial adjusted doses according to local practices after an additional dosing phase. The researchers found that the PGx algorithm gave only an insignificant advantage at 12 weeks, with PGx patients in range 61.6% of the time and control patients in range for 60.2% (N Engl J Med 2013;369:2304–12).

Assessing Study Differences

A key factor in the more successful EU-PACT trial was loading of the doses, says Pirmohamed. Patients got the largest doses on the first day of therapy, and less on the two subsequent days, to get them to a steady state early on because of warfarin’s long half-life, he explained, noting that the COAG trial did not use this strategy. Other important differences from the COAG trial, he added, were use of POC devices that enabled his team to have patients' genotypes before any dosing began, as well as a longer study period.

Different algorithms used in the first EU-PACT trial and the COAG study are another key difference, said Stephen E. Kimmel, MD, COAG trial's first author and professor of medicine in the cardiovascular medicine division at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia. Dosing of patients in COAG's PGx arm followed an algorithm that considered not only genetics, but also clinical variables. COAG sought to tease out the effects of genotype while controlling for clinical variables.

An editorial by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research officials that accompanies the papers agrees that the COAG attention to these factors may have influenced results. It is unlikely that addition of genotype information as a covariate in a relatively small proportion of the overall study population would have a notable effect, given COAG’s attention to non-genetic factors, wrote Issam Zineh, PharmD, MPH, Michael Pacanowsky, PharmD, MPH, and Janet Woodcock, MD (N Engl J Med 2013;369:2273–5).

One lesson from the COAG trial is the strength of its clinical dose refinement algorithms, said COAG investigator Brian F. Gage, MD, professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. "Over the past 10 years, we've realized that although genotype is important, optimal clinical dosing… needs to incorporate clinical factors, warfarin-drug interactions, pharmacokinetics, and initial INR response," he added.

COAG's inclusion of so many African Americans may have diminished the percentage of time the entire control group remained in range, EU-PACT’s Pirmohamed said, while Kimmel noted that COAG tested for variants that are less common among African Americans. Research shows that their metabolism of warfarin may be influenced by other variants in VKORC1 and CYP2C9, and other genes, including CYP4F2 and maybe APOE (Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010;87:459–64, Pharmacogenomics 2012;13:1925–35, and Lancet 2013;382:790–6).

Another significant difference is that the COAG trial was double-blinded, whereas the first EU-PACT study was single-blinded, according to Kimmel. While he maintained that knowledge of trial arm can affect how carefully patients take warfarin or clinicians care for patients, Pirmohamed disagreed, noting that his patients were blinded so they could not have taken warfarin more carefully.

While the primary endpoint of the second EU-PACT trial—time in range over 12 weeks—indicates little advantage for PGx dosing of acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon, it did show a modest improvement in time in range for the PGx arm at 4 weeks. At this time point, the proportion of PGx patients in range was 5.3% more than that of control patients, noted Anke-Hilse Maitland-van de Zee, PharmD, PhD, senior author of the trial and associate professor of pharmacogenetics/genomics at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. "This first month might be of importance," she noted, adding that her study was not as convincing as she had hoped.

Still Looking for Answers

While they agreed results of studies were somewhat disappointing, study authors and others familiar with PGx dosing had different ideas about what they mean for laboratorians.

Pirmohamed suggested paying attention to data from the trials that most closely matches laboratorians' own settings, populations, and local practice patterns. For example, those in hospitals that use loading dosing strategies may want to take a closer look at his study. Laboratorians who work with physicians who do not use loading dosing may want to focus on the COAG trial, he added.

But Kimmel was more pessimistic about his own trial and the others. "The message from COAG is that information you get from genotyping is unlikely to provide a further benefit beyond the information clinicians already have about patients," he said. "There's no value in using it routinely. Right now I don’t see a future for PGx in clinical care of warfarin-treated patients,” he added, noting most U.S. insurers, including Medicare, do not pay for it.

Maitland-van der Zee predicted that the conflicting study results, coupled with only a modest advantage noted by the first EU-PACT trial, will dampen both clinician and study funders' enthusiasm for PGx dosing of warfarin and other vitamin K antagonists.

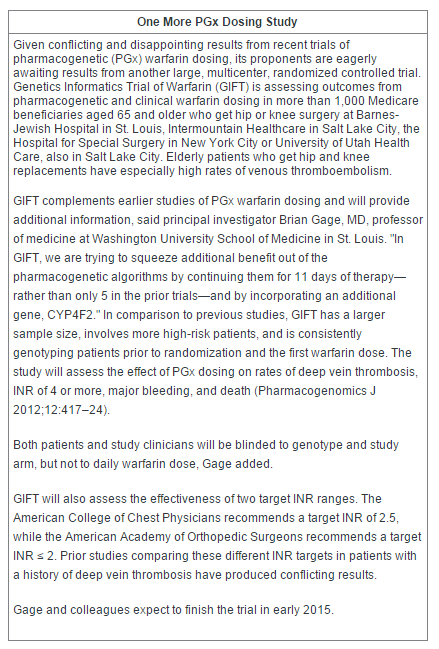

All of these researchers and others interested in PGx warfarin dosing are waiting for results from one more large trial. This multicenter study, led by Gage, will evaluate PGx in orthopedic patients (See Sidebar, above). "That will give us four RCTs. If Gage’s study is negative, it really will be the last nail in the lid," said COAG investigator Charles S. Eby, MD, associate chief of the division of laboratory and genomic medicine, professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine and author of a 2009 Clinical Chemistry commentary which argued against PGx testing to dose warfarin, citing lack of evidence of its effectiveness. A companion commentary by Mia Wadelius, MD, PhD, last author of Pirmohamed’s EU-PACT study, also called for more data.

The Academic Factor

The studies' settings—academic medical centers that frequently measure INR in accordance with practice guidelines—may confound results, FDA officials wrote. "Any differential effect between one intervention and the other may be obscured, since either strategy, when combined with frequent adjustments based on INR, is likely to be superior to what is currently practiced in the community," they explain.

That's an important point, said Thomas Moyer, MD, emeritus professor of laboratory medicine, former chair of the department of biochemistry and immunology, and vice chair of the department of laboratory medicine and pathology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a co-author of a large study that showed PGx-based warfarin dosing reduces the risk of hospitalization by approximately 30% (J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2804–12). Frequency of INR monitoring is a key factor in how well warfarin works, he noted. "At academic medical centers, patients on warfarin are put onto rigid protocols. In the first week, they get INR measured three to four times, twice in weeks two and three, and weekly monitoring though week 10, with dosage adjustments," he noted, adding that INR in other community settings is often far less frequent and inconsistent with 2011 guidelines on PGx warfarin dosing from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;90:625–9). As a result, the incidence of adverse events requiring readmission in most community hospitals is three times the rate seen at academic medical centers, he indicated.

Rather than studying PGx dosing, research should focus on how more frequent INR monitoring, improved clinician communication with patients and labs, and better patient adherence to therapy affects effective warfarin dosing, said a second editorial that accompanied the three studies. Bruce Furie, MD, of the Harvard Medical School and the Division of Hemostasis and Thrombosis at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, added that rates of bleeding and thrombotic complications may be more useful as endpoints than time within therapeutic INR range.

For laboratorians, the bottom line for viewing these studies and making decisions about implementing PGx testing for warfarin administration is the classic question of whether the test changes patient management, said Neil Harris, MD, clinical associate professor in the department of pathology, immunology, and laboratory medicine and director of the core laboratory at University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville. "The answer is no. If I’m asked to do pharmacogenetics in my lab now, I'd say there's not enough evidence to support it."

Moyer predicts the three studies will have little impact on future guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians. Currently they do not recommend PGx testing prior to warfarin therapy, but advise it if a patient is not stable after 2 weeks, he explained. The recent lackluster data are secondary to the rising popularity of new, heavily marketed anticoagulants that do not require INR testing, he said, adding that these drugs will likely dominate discussion of updates to the guidelines. Although these medications—Xarelto (rivaroxaban), Eliquis (apixaban), and Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate)—cost almost 10 times as much as warfarin, Medicare will pay for some of them, and when they are used, community hospital labs need not wait 3 days or more to get PGx testing results from reference labs, Moyer noted.

The new anticoagulants are also popular in Europe. Maitland-van der Zee said she had difficulty recruiting patients to EU-PACT because so many preferred the new drugs.

"For laboratorians, the message is 'business as usual'," Moyer said. “Don’t expect PGx to become standard care."

Disclosures: Stephen Kimmel has done consulting for Pfizer Inc. and serves on a data safety monitoring board for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, but not in a capacity related to warfarin or other anticoagulants.

Deborah Levenson is a freelance writer based in College Park, Md. Her email is [email protected].