An Interview with Nikola Baumann, PhD, DABCC

Thanks to automated systems and other advancements, the number of errors occurring today in the analytical phase of laboratory testing has been drastically reduced. While these advancements in laboratory testing have led to rapid reporting of large numbers of patient samples, laboratories now face a new type of problem: systemic errors that could impact many patient results before the laboratory even detects the error. In this interview, Nikola Baumann, PhD, director of the Central Clinical Laboratory and Central Processing at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., offers ideas and suggestions on how to prepare for and recover from large-scale testing errors.

Corinne Fantz, PhD, of the Patient Safety Focus Editorial Advisory Board, conducted this interview.

What is a large-scale testing error?

Large-scale testing errors are errors that impact multiple patients. Valenstein, et al. published an informative article on this topic and used the term large-scale testing error to mean "an error that impacts a large number of laboratory results because of a defect in a system used for high-volume testing" (1). Much of the focus on errors in healthcare settings, including laboratory medicine, has been on error rates calculated from adding up single-error occurrences. These data have sensitized laboratorians to high error rates in the pre-analytical and post-analytical phases of laboratory testing. These single mistakes often occur outside the walls and immediate control of the laboratory.

At the same time, laboratorians are well aware that the analytical phase of testing, the phase that the laboratory actually controls, has the lowest error rate. Interestingly, although single errors are less frequent in this phase, errors that impact multiple patients are more common. With total laboratory automation and high-throughput analyzers, laboratories can now consistently produce more results in less time and with fewer human resources. Stable operation is the norm and when a systemic error occurs in these sophisticated systems, the laboratory may not detect the problem until tens, if not thousands, of patient results have been released into the medical record.

In the Central Clinical Laboratory at Mayo Clinic, we report more than 5.4 million billable test results annually. Over a 1-year period, we detected 15 testing errors that impacted >20 patients. We monitor analytic quality closely, and in most of these cases, the analytical errors were detected and corrected in real time. However, these data suggest that a high-volume, automated laboratory could potentially encounter one or more large-scale testing errors per month. In the absence of well-designed quality control (QC) processes, it may not be possible to detect such errors and correct them expeditiously.

Do you have the right tools to deal with large-scale laboratory errors?

Do you have the right tools to deal with large-scale laboratory errors?

Being prepared to respond is essential to recovering and protecting patient safety.

Are there certain operational vulnerabilities that laboratories may not recognize that put them at greater risk for large-scale errors?

There are two practices in the laboratory that make us more vulnerable to large-scale testing errors. The first is performing QC for the sake of performing QC. We should remind ourselves and our laboratory staff that we use QC to ensure stable operation. Running controls until "they come in" or repeating between instrument comparisons "because the first one didn't match" are red flags. To detect errors, we need to trust our quality control processes and react to failures.

The second practice that makes us vulnerable is not openly communicating with our end users. Clinicians are robust error detectors. They will notice a questionable result, repeat the test, and if the repeat test result makes sense in the clinical context, all is well in their mind. But the clinician may never tell the laboratory about the error, which means that the problem may continue. Open dialog between the laboratory and clinical services should be cultivated and encouraged as an additional valuable quality assurance (QA) tool.

To circumvent vulnerabilities in a laboratory's operations, robust error detection methods also should be a top priority. Those who work with me will often hear me say that I am encouraged when I see our laboratory error rate increase because it means that we are catching errors. It also means that we have the opportunity to fix what went wrong. Our greatest fear as laboratorians should be that we are missing errors. Coincidentally, the "best" laboratories, or those with the lowest error rates, may actually have the worst error detection systems.

Robust error detection can be achieved in high-volume, mass-production settings by designing and implementing multiple and redundant QC and QA methods and matching the frequency of these activities to the lab's volume and throughput. It also is important to ensure quality across the total testing process. Post-analytic errors caused by incorrect instrument settings, calculation errors, and correction factors are sometimes the most difficult to detect.

The response to a large-scale testing error tends to take place in a tense environment. Who should be notified when a large-scale error occurs?

It is good practice to have a policy or procedure for responding to testing errors that impact multiple patients. By being proactive and planning for these inevitable occurrences, laboratorians can take the panic factor out of the response and recovery phase.

The policy should include a list of key individuals who need to be notified immediately, usually the laboratory supervisor, manager, and director. Once laboratory leadership is aware of the issue, a response team, including quality unit representatives, risk management, and possibly legal, billing, information management, and clinician representation should be formed. Obviously, care providers also must be notified and corrected results or re-testing should be offered as appropriate. The response team should determine how to most effectively notify providers and other stakeholders within and outside the institution.

What strategy should laboratories use to develop a policy or procedure for managing large-scale testing errors?

It is important to recognize that a standardized approach to corrective action and managing risk to patients is not possible due to the large variability in errors and in how laboratory test results are used in clinical management and treatment decisions. Based on reports in the literature, approximately 8–15% of laboratory errors will have a direct effect on patient care, while the risk of inappropriate care due to a laboratory error is typically lower (2). Therefore, risk assessment is an important component of the recovery phase.

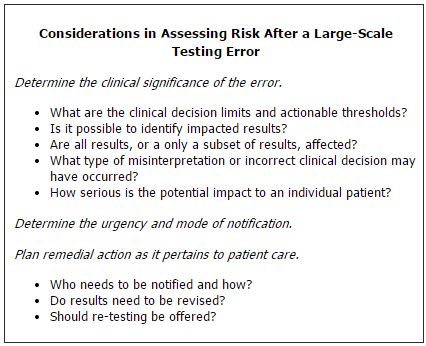

Paula Santrach, MD, associate dean in the Office of Value Creation at Mayo Clinic, and I presented an interactive workshop on this topic at the 2012 AACC Annual Meeting. We proposed a checklist to aid in managing recovery from large-scale testing errors. Once the nature and scope of the testing error are identified, the response team should focus on some common elements to assess risk and patient impact (See Box).

What obligations to constituencies do laboratories have beyond the immediate care provider and/or patient where the error happened?

While patient care and minimizing risk to patients should be first and foremost in the response and recovery plan, laboratories do have an obligation to consider broader implications and to communicate their findings (1). Diagnostic manufacturers should be notified immediately of errors caused by defects in their products including instrumentation, reagents, and calibrators. In our experience, most vendors are very responsive and will cooperate in investigations and reimburse laboratories for expenses related to investigation or re-testing samples. For tests cleared or approved by the Food and Drug Administration, manufacturers must report medical device failures and adverse patient outcomes to the agency and notify other customers as appropriate. If the vendor does not respond appropriately, I believe laboratories have an obligation to escalate issues directly to regulatory or accreditation agencies. Depending on the situation, notification plans also may include making a public disclosure and responding to media inquiries at the organizational level.

Finally, the scope of the testing error and its impact on patients should be shared openly with laboratory staff to reinforce a culture in which it is both safe and beneficial to disclose errors.

Where would a root cause analysis fall in the recovery efforts of a lab after a large-scale testing error?

The highest priority in recovery is containment and immediate prevention of further errors. Depending on the nature of the error, interventions may include discontinuing testing, duplicate testing, or testing at a different facility. Root cause analysis is the next necessary step. After identifying the laboratory testing error, laboratories should determine the root cause as quickly as possible. In fact, root cause is often needed for defining the scope of the testing error and developing contingency plans. In my experience, large-scale testing errors are highly variable and it may take several weeks or more to fully elucidate the root cause.

For example, a clinician calls the laboratory questioning an erroneous result that was reported on a patient. The laboratory no longer has the sample for retesting but initial findings suggest that the erroneous result may be due to a common drug that interferes with one laboratory method. An alternate method is used to confirm that the interference is indeed method-specific. While the single error can now be explained, the laboratory has identified a potential large-scale testing error that will need further investigation and response. In this example, prompt and thorough root cause analysis aids in detecting a large-scale testing error and in defining the scope of the error. It is important to acknowledge, however, that root cause analysis in these situations can take weeks or months and that communication to care providers should not be delayed while the analysis is being conducted.

When should payment credits be issued as a result of a large-scale testing error?

When the laboratory knows that an erroneous result was reported, the charges for this test should be credited or re-testing should be offered free-of-charge. However, this is not always straight forward. If the large-scale testing error has been occurring over the past 2 years and impacts approximately 1 in 500 patient results, one could imagine it becomes challenging to identify patients who may have been impacted or to reverse charges from years ago. Whenever possible, the institution should use the laboratory information system and electronic medical record data to identify affected patients. As mentioned earlier, it is often useful to have an individual with laboratory billing expertise on the large-scale testing error response team to facilitate the logistics of payment credits.

How does a culture of organizational transparency and safety play a role in helping labs recover from large-scale testing errors?

Leaders in our field have emphasized the importance of the Fair and Just Culture model for many years (3). Today, many laboratories have come to recognize the importance of this culture and the grass roots approach to handling errors. Medical laboratory technologists need to have a sense of ownership for the results they are reporting, and supervisors, managers, and medical directors need to lead in an environment of open and honest communication and continuous improvement.

Equally important is transparency within the organization. Errors in medicine, including laboratory errors, should be used as teaching tools and opportunities to learn from our mistakes and improve.

REFERENCES

- Valenstein PN, Alpern GA, Keren DF. Responding to large scale testing errors. Am J Clin Path 2010;133:440–6.

- Plebani M. Errors in clinical laboratories or errors in laboratory medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2006;44:750–9.

- Hernandez J. How to modify staff behavior that puts patients at risk: The Just Culture model. Clin Lab News 2009;35 (10):17.