Pregnancy places unique demands on the thyroid gland and thyroid function, and has been called a stress test for this master regulator of metabolism. As many as 5% of pregnant women experience some sort of thyroid dysfunction, putting themselves and their babies at risk for short- and long-term health complications. Yet these common, potentially serious thyroid imbalances often are under-appreciated and may go undetected. Now, two new guidelines not only are raising the visibility of thyroid disease in pregnancy and calling attention to issues in need of further research, but also underscoring the importance of close laboratorian-clinician collaboration around thyroid test ordering and interpretation.

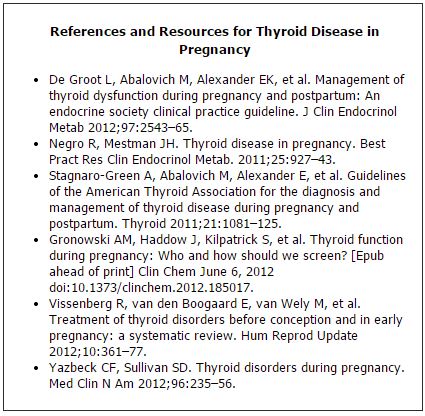

"I don't think thyroid disorders get the attention they deserve in terms of research, publications, and awareness. One of the best things about these guidelines is they make frontline physicians think about thyroid health in pregnancy, because in terms of getting attention it's way down the list. We're always worried about preeclampsia, preterm birth, growth restriction, obesity, and diabetes, so thyroid disorders tend to fall off the radar screen," explained Scott Sullivan, MD. "Any information labs can provide that guides doctors in knowing which tests to order and how to interpret pregnancy-specific reference ranges would be helpful." Sullivan, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, served on committees for the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and the Endocrine Society, both of which recently issued guidelines on diagnosing and managing thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy (Thyroid 2011; 21:1081–125; J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97: 2543–65).

One of the challenges in raising the profile of thyroid health in pregnancy is that the two most common thyroid problems, overt and subclinical hypothyroidism, present like normal pregnancy. "It's difficult to make the diagnosis of hypothyroidism in pregnancy unless it's really far advanced because a lot of the symptoms of pregnancy are also symptoms of hypothyroidism. It's not that physicians aren't capable of doing so; it's just that this condition can be crippling but in ways that are not obvious," observed James Haddow, MD. "Fatigue, weight gain, and constipation are part of our lives. So we have to be respectful that it's not an easy clinical diagnosis. That's one of the reasons I'm really strongly in support of routine thyroid function testing, especially during pregnancy." Haddow, a research professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I., has a long-time interest in pregnancy-related thyroid issues, including conducting seminal research on the relationship between thyroid deficiency and pregnancy complications.

The Thyroid in Pregnancy

During pregnancy, rising human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels stimulate the thyroid to produce more thyroid hormone, causing thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) concentrations to dip below normal, particularly in the first trimester. Elevated hCG levels also lead to temporary increases in free thyroxine (FT4) and free thyroxine index (FT1) during the first trimester, but in normal pregnancy these measurements usually stay within the nonpregnant range.

Increased estrogen levels in pregnancy also change concentrations of thyroid hormones, most notably thyroid binding globulin (TBG), which rises starting a few weeks into pregnancy and levels off mid-term at about two-to-three times above normal, where it remains until delivery. This increase, in turn, leads to higher levels of total thyroxine (TT4) and total triiodothyronine (TT3) throughout pregnancy (See Table, below).

The body's demand for iodine, which is essential for thyroid function, also increases in pregnancy. Several mechanisms are at play, including boosted thyroid hormone production brought on by higher levels of hCG and estrogen. The mother's glomerular filtration rate also rises early in pregnancy, thereby clearing more iodide, and lowering the circulating pool of plasma iodine. In addition, before week 12 of gestation, some maternal iodine stores transfer to the fetus to enable its thyroid gland to start functioning.

What's the TSH Reference Range?

Based on recent research, both the ATA and Endocrine Society recommended trimester-specific reference ranges for TSH, with upper limits of 2.5 mIU/L in the first trimester and 3.0 mIU/L in the second and third trimesters. This compares with an upper limit of 4.0 mIU/L in healthy, nonpregnant individuals. Black and Asian women typically have TSH values 0.4 mIU/L lower than in Caucasians, a difference that persists in pregnancy. ATA emphasized the importance of lab- and population-specific reference ranges (See Table, below).

|

Recommended Trimester-Specific TSH Reference Ranges

|

| First |

Second |

Third |

| 0.1–2.5 mIU/L |

0.2–3.0 mIU/L |

0.3–3.0 mIU/L |

| Source: Thyroid 2011;21:1081–125 |

The guidelines define subclinical hypothyroidism as a serum TSH level above the upper limit of the trimester-specific reference range but with a normal FT4. Overt hypothyroidism also involves a serum TSH level above the upper limit of the trimester-specific reference range, but with a decreased FT4 level. When pregnant women have TSH levels >10 mIU/L, they are considered to have overt hypothyroidism regardless of their FT4 levels. Two thirds of undiagnosed pregnant women in this category will become permanently hypothyroid, and an average of 5 years will elapse before a clinical diagnosis is made in the absence of testing.

How Robust are FT4 Assays?

Both panels acknowledged challenges with FT4 immunoassays, in that they are sensitive to changes in binding proteins. According to the ATA panel, "high TBG concentrations in serum samples tend to result in higher FT4 values, whereas low albumin in serum likely will yield lower FT4 values." The panel went on to suggest that even though FT4 immunoassays perform reasonably well, values should be interpreted using method- and trimester-specific ranges since studies have shown that reference intervals vary widely between methods. ATA also lauded solid phase extraction-liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) in dialysate or ultrafiltrate as a "major advance" with higher specificity than immunoassays. Although ATA cited the method as being "ideally suited for generating reliable, reproducible trimester-specific reference ranges for FT4," the panel acknowledged that LC/MS/MS is not widely available. The Endocrine Society panel also recommended establishing trimester-specific reference ranges for FT4, but in addition suggested either using the free T4 index or multiplying the nonpregnant TT4 range, 5–12 µg/dL, by 1.5.

"Many FT4 immunoassays are not terribly robust in pregnancy because the very high TBG levels seem to throw off the results in unpredictable ways. A number of studies suggest that most commercially available FT4 assays may be unreliable in pregnancy," said ATA panelist Elizabeth Pearce, MD, MSc. "The ATA official recommendation was solid phase extraction LC/MS/MS, which is available in select locations. It does work very well, but almost no one has it. We came to the conclusion on our panel that in the absence of access to a gold-standard assay you have to know your local assay, develop a feel for how it works in pregnancy, and be aware that the TSH is a more reliable measure in most circumstances. The Endocrine Society panel also had concerns about the usefulness of most of the FT4 assays in pregnancy, but they specifically recommended use of the free thyroxin index. That's one of the more significant differences between the guidelines." Pearce is an associate professor of medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine.

Making the Outcomes Connection

The association between maternal thyroid hormone and iodine levels and outcomes for both mother and baby have been the focus of considerable research and controversy. Overt hypothyroidism in pregnancy clearly has been linked to increased risk of premature birth, low birth weight, and miscarriage. Evidence about how subclinical hypothyroidism affects pregnancy outcomes has been less consistent.

Studies also have associated maternal hypothyroidism with cognitive challenges in offspring, albeit with conflicting results. Reports dating to the early 20th century showed a correlation between mothers with iodine deficiency and mental retardation in their babies, but in the modern era, research involving pregnant women with less severe hypothyroidism unrelated to iodine deficiency has yielded less consistent findings. Haddow's study from 1999 found that children ages 7–9 years born to women with overt, undiagnosed hypothyroidism during pregnancy were more likely than controls to have an IQ ≤85 as well as motor, language, and attention delays, but the association was not statistically significant. To the disappointment of many in the field, results from a long-awaited randomized trial published in February found that antenatal screening and maternal treatment for hypothyroidism did not lead to improved cognitive function in children at 3 years of age (N Engl J Med 2012;366:493–501).

Is Universal Screening Warranted?

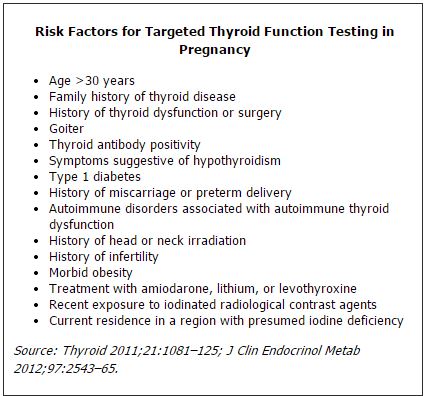

Lack of research definitively linking screening and intervention for subclinical hypothyroidism to improved outcomes has evoked considerable debate in the endocrine and obstetrical communities. The ATA guideline committee ultimately determined that there was not enough evidence to recommend for or against either universal TSH or FT4 screening in pregnant women or preconception TSH screening in women at high risk of hypothyroidism. However, the committee did recommend TSH testing early in pregnancy in women at high risk for overt hypothyroidism (See Table, below).

Reflecting the controversy in this area, the Endocrine Society committee could not reach a consensus on whether all newly pregnant women should have TSH testing. Five panelists supported screening all pregnant women at their first obstetrical visit, while eight others were neither for nor against universal screening, though they strongly supported aggressive case finding to identify and test high-risk women. Meanwhile, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend against routine testing during pregnancy.

Sullivan summarized the divergent opinions and lively discussion on this subject. "There's a group of people who feel passionately for all the right reasons that everyone should be screened. Other experts feel because of the lack of data and because of cost it shouldn't be done. Then there are people in the middle, like me, who have sympathy for both points of view. Being on both panels, I can't count the number of hours that I've heard the arguments. It was a close call." The endocrinology community, he explained, "favors screening because they're really concerned about prenatal outcomes. However, the obstetrical community is more cautious and conservative. We've been burned by screening programs in the past, incompletely thought out and based on incomplete data, that now we're stuck with. We also have more of a medical liability crisis than other specialties, so if there's a recommendation or guideline and you stray from it, you open yourself up to litigation."

Supporters of universal screening now are looking forward to results from an ongoing study of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which is not expected to publish results for at least a couple of years. The ATA panel acknowledged the evolving science in this area. "The committee recognizes that knowledge on the interplay between the thyroid gland and pregnancy/postpartum is dynamic, and new data will continue to come forth at a rapid rate. It is understood that the present guidelines are applicable only until future data refine our understanding, define new areas of importance, and perhaps even refute some of our recommendations," wrote the panel.

Given the conflicting guidelines and incomplete and inconsistent evidence, TSH testing patterns in pregnant women appear to be all over the map. In a study published last year, Pearce found that 85% of women being followed at Boston Medical Center were screened during their first obstetrical visit. Meanwhile, Quest Diagnostics in 2012 reported that overall, 23% of the more than 500,000 for whom it performed pregnancy-related testing had TSH testing (J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:777–84). Haddow also reported finding that about half the pregnant women in Maine were routinely being tested for TSH levels.

"I think there's a huge amount of regional variation," observed Pearce. "In the setting of conflicting guidelines, people are doing a variety of different things, and whatever they're doing there's probably a guideline out there to support it."

What's the role of TPO Antibodies?

If the guidelines diverged somewhat on TSH and FT4 testing, they concurred in not endorsing universal thyroid antibody screening in pregnancy. A recent prospective trial and some retrospective studies have found the risk of pregnancy complications to be more pronounced in women who have both subclinical hypothyroidism and who are anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) positive. Both TPOAb and thyroglobulin antibody positivity also have been associated with pregnancy loss, but noting that an association does not equate to causality, the ATA panel found insufficient evidence for thyroid antibody screening.

In Sullivan's experience, confusion about thyroid antibody testing causes it to be underutilized, even in cases in which it could help resolve other inconclusive tests. This presents a real opportunity for laboratorians to step in and help clinicians, he argued. "When I talk to other obstetricians, they like to hear about iodine deficiency and screening for subclinical hypothyroidism, but when I start talking about antibodies, they just tune me out. That's an area where we have a lot of work to do, because there still remains a lot of confusion," he explained. "There are so many different names for the same thing. TPO and anti-peroxidase antibodies, for example. People don't know those are the same thing. When I've spoken to non-specialist obstetricians they've all but abandoned ordering these tests because it's so frustrating for them, and that's a disservice."

User-friendly Testing

Experts consulted for this article agreed that TSH by far is the most important test of thyroid function in pregnant women, although Haddow and others emphasized the importance of establishing trimester-specific reference ranges and providing interpretive comments to aide physicians in evaluating test results in the context of patients' clinical status.

"My feeling at the moment is that measurements of FT4 and TPO antibodies can contribute useful supplementary information when TSH is outside the reference range, even though there can be certain instances when FT4 assay values don't correlate with the original dialysis method. It should be possible to perform them in a straightforward manner," observed Haddow. "That said, the obstetric community is somewhat confused right now because of the conflicting recommendations, and the laboratory has a responsibility to provide not just the test result but an interpretive statement that's based on the recommended trimester-specific cutoffs. That will go a long way in terms of helping the physician."

Shannon Sullivan, MD, PhD, also argued for some way, either by electronic health record or test requisition form, for a physician to be able to inform the lab that a patient is pregnant, thereby facilitating better communication between the two. "If a pregnant woman came in with a TSH of 15 mIU/L, I'd consider that a critical lab value, but it certainly would not be called into the physician as critical because the lab typically wouldn't be aware the patient is actually pregnant," she said. "On the lab requisition form there could be a box the physician could check to indicate that the patient is pregnant. I've never seen that before, but it would give the person who is running the test and reporting back to physicians any critical values a heads up that this lab value is abnormal for a pregnant person." Sullivan, unrelated to Scott Sullivan, is an endocrinologist at Washington Hospital Center and an assistant professor of medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine in Washington, DC.

Another area of concern to both Sullivans is occult iodine deficiency. Both guidelines recommend 250 µg iodine daily in pregnant women. However, probably in deference to the U.S. overall being an iodine replete country, the Endocrine Society guidelines explicitly do not advise as part of normal practice measuring urine iodine concentration (UIC), which, while being a validated measure of population iodine status, is not reliable for individuals, due to wide day-to-day and diurnal variations. Yet both Sullivans are seeing in their respective practices growing numbers of patients who are iodine deficient, sometimes severely so. Both attributed this to a confluence of factors, including public health advisories about the need to decrease salt intake and for pregnant women to avoid tuna, the growing popularity of non-iodized sea salts, and reliance on processed foods, which do not use iodized salt. In addition, not all prenatal vitamin formulations contain iodine.

How this trend will be incorporated in future guidelines or factored into testing patterns remains to be seen. In the meantime, experts emphasized that laboratorians are important players in guiding physicians through the complex and sometimes confusing domain of thyroid function testing in pregnancy.