As the healthcare system prepares to cope with an influx of 30 million Americans who will have health coverage as a result of the Affordable Care Act, a surging market of retail clinics is poised to take on a wider role to relieve the bottleneck. No longer merely an anomaly or an experiment of a few drug store chains, retail clinics have steadily expanded. While most only have a corner of real estate inside their host retailer, these quick-service healthcare establishments are widening the scope of care they provide. Over the last few years, many have added more advanced services and tests, partnering with health systems and insurers to become embedded in local healthcare ecosystems.

According to experts, quick-access clinics can be one part of the solution to improving access to basic healthcare. Some insurers and healthcare systems already have retail clinics in mind for more than just minor, acute care visits, according to Tom Charland, chief executive of the research and consulting firm Merchant Medicine, which tracks the retail medicine market. "Insurance companies are now recognizing that pharmacies and retail clinics can do chronic disease management pretty efficiently. We are in the early stages of this area, but the scope is definitely changing," he said.

Not only do insurers see retail clinics as facilitators of disease management, but also as a stop gap measure for the growing shortage of physicians. "In geographies where there are critical shortages of primary care physicians, some insurance companies are even paying retail clinics to act as a medical home," Charland continued. "If there is no primary care physician, the insurers would rather have somebody than nobody. And they feel that nurse practitioners in these clinics are fully able to act as patients' primary care providers."

Growth Signals Turnaround

Retail clinics first began making news in 2000, but after an initial jump, some closed their doors only a few years later, with some observers calling the model a failure. Since the mid 2000s, however, the industry has rebounded, with more than 1,300 clinics around the country and nearly 12% growth in 2011, according to Charland. Industry leader MinuteClinic opened 19 new clinics just in September.

While CVS Pharmacy's MinuteClinic and Walgreens' Take Care Clinic still dominate, Target and Walmart are expanding their clinic presence, and dozens of health systems are opening their own retail-style clinics, such as Geisinger's Careworks walk-in clinics (See Box, below).

|

Retail Clinics Expand, Diversify

|

| Operator |

Clinics |

| MinuteClinic |

588 |

| TakeCare |

356 |

| Walmart Partners |

143 |

| The Little Clinic |

89 |

| Target Clinic |

53 |

| FastCare |

31 |

| RediClinic |

29 |

| Dr. Walk-In Medical Clinics |

13 |

| Aurora QuickCare |

10 |

| Lindora Health Clinics |

9 |

| Alegent Quick Care |

6 |

| Family Quick Care |

5 |

| Geisinger Careworks |

5 |

|

As of October 1, 2012.

Source: Merchant Medicine LLC

|

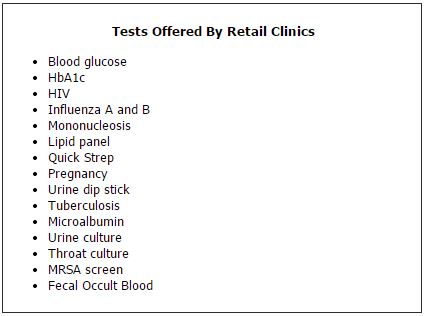

Retail clinics are also adding new tests that go far beyond caring for scraped knees and scratchy throats. The growing list of tests includes lipid panels, HbA1c, microalbumin, HIV, fecal occult blood, influenza A and B, and even screening for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clinics offer many of these tests as part of adult and child physicals, and more recently, Medicare wellness visits (See Box, below).

A recent study found that patient traffic to retail clinics doubled every year between 2007 and 2009, reaching nearly 6 million visits in 2009 (Health Aff 2012;31:2123–29). Patients spent an average of $78 per visit, which translated into about $460 million in 2009. While a significant amount of this volume was attributed to flu shots—an area in which pharmacies now compete more than they did in 2009—the study showed that consumers increasingly accept and value the convenience of clinics. The authors noted that nearly 50% of retail clinic visits take place during hours that physician offices are not open.

Laboratorians will feel little comfort knowing they are not the only healthcare professionals worried about a staffing shortage. The American Association of Medical Colleges warns that by 2020, the nation will face a shortage of 45,000 primary care physicians. This crisis will become especially serious when, in 2014 and beyond, the healthcare reform law reaches full effect, pulling some 30 million people into the healthcare system through Medicaid and subsidized private insurance.

The expected influx of newly insured patients under the Affordable Care Act provides both opportunity and uncertainty for the retail clinic model, according to the lead author of the study, Ateev Mehrotra, MD.

"If more people are seeking primary care, and there is no dramatic increase in the number of primary care physicians, we could face a situation of increased demand and worsening access. Without an alternative, more patients may go to a retail clinic," he said. "The flipside is that a significant segment of patients who go to a retail clinic don't have a primary care physician. If under healthcare reform more people gain access to primary care physicians, it's still possible they could choose the physician's office over the retail clinic." Mehrotra is a policy analyst at the RAND Corporation and an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Notably, in Mehrotra's study, nearly 70% of patients were covered by insurance. This figure was no surprise to Charland, who emphasized that retail clinics cater mainly to middle-class families. "The biggest driver for retail clinics is still convenience. There is this fallacy out there that all these clinics do is cater to the uninsured. And that's just not true," Charland said. "It's busy, dual-income, educated, working parents whose kids are also busy. When someone gets sick in the household, it's chaos. And for the doctor's office to say they can only see you on a certain day at a certain time, that just doesn't cut it anymore." Charland has been involved in retail medicine since 2003. He served as senior vice president of strategy and business development at MinuteClinic and helped develop the company's early relationship with CVS Pharmacy, as well as with insurers.

In addition to more patients with insur-ance, changes to insurance plans themselves will drive patients to retail clinics as well, Charland predicted. "High-deductible health plans, which are expected to become more common, will also mean growth for retail clinics," he said. "The transparency of pricing is important to people because it's now coming directly out of their pockets. And you don't have the situation where you don't know what you paid until 60 days later when the explanation of benefits comes in the mail. Healthcare is the only industry in this country where you can buy something, and you don't know what you paid for it. But that's not the case with retail clinics, and people are drawn to that."

Collaborations Deepen Ties to Healthcare System

Early on, the largest chains of retail clinics entered the market as an extension of national pharmacies, such as MinuteClinic in CVS and Take Care Clinic in Walgreens. Today, many clinics partner with health systems outside the walls of the store in which they reside. For example, MinuteClinic now has deals with 18 health systems, representing more than 150 hospitals. Walmart also has deals with more than 12 health systems or physician groups, representing some 137 clinics.

In one of the most recent collaborations, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) announced in July that UCLA Health System physicians will serve as medical directors for 11 MinuteClinics in Los Angeles County. They also will work together on patient education and disease management programs. Tightening the relationship, MinuteClinic and UCLA already have started to work toward fully integrating their electronic health record (EHR) systems in order to share medical histories and visit summaries with other UCLA locations. In announcing the deal, UCLA Health System president David Feinberg, MD, noted that UCLA hoped to "explore new and innovative ways to deliver patient care and manage chronic conditions."

UCLA's Bernard Katz, MD, told CLN that for the most part, physicians at UCLA have supported the partnership. "There may be some primary care physicians who feel that this is a competition for the same patients, but I think that most understand that these clinics are facilities where their patients can get care in a kind of outreach setting that is like an extension of their office," he said. "In these days of more and more difficult access to primary care, we think this partnership will open up new avenues for our patients to get the high-quality care that they need."

Katz, who is the physician coordinator of the MinuteClinic collaboration, also noted that MinuteClinic will ask patients if they have a primary care relationship, and if they don't, encourage them to establish one. The plans for how MinuteClinic might help UCLA manage chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension are still in the early stages, but they revolve around sharing information via EHR.

As health systems move toward an accountable care organization (ACO) model that emphasizes outcomes and efficiency, collaborations with retail clinics could be part of the strategy. "Because accountable care is about population management, MinuteClinic could be a great way for patients who are part of the UCLA health system to have better access to care that is convenient and still coordinated through the EHR in an ACO model," he said. UCLA is still in the process of assessing how it will adapt to the ACO model.

Widening Scope of Care Sparks Criticism

As retail clinics have grown in number and ventured into the sphere of chronic disease management, they have also met with stern criticism from some physician groups, such as the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).

AAFP has been vocal in opposing any expansion of the scope of service in retail clinics that approaches managing chronic conditions. It believes that high quality and coordinated care depend on relationships with primary care physicians—a relationship with which retail clinics interfere.

"AAFP believes that the best healthcare comes from a patient-centered medical home, where you have a strong primary care focus with comprehensive, coordinated, and continuing care," said AAFP president Jeffrey Cain, MD. "When retail clinics start talking about managing chronic disease or performing well adult exams, that's further fragmenting an already fragmented health system. We believe patients will have better care and better quality if they find that care within an ongoing relationship to a primary care physician who knows that person." Cain is chief of family medicine at Children's Hospital Colorado and associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Aurora.

According to Cain, family physicians have responded to the demand for greater flexibility by expanding access to appointments. "Family doctors have responded so that about 75 percent of their offices have open-access, same-day appointments and about half have evening or weekend office hours," he said. Results from an AAFP physician survey also found that about 31% of respondents offered weekend appointments.

Both AMA and AAFP are urging insurers not to give patients an incentive to use retail clinics, warning of the potential for duplicative tests and treatments, higher costs, and lower quality.

Tine Hansen-Turton, executive director of the Convenient Care Association (CCA), which represents retail clinics, admits that retail clinics amount to "disruptive innovation." However, she emphasized that the industry has committed to quality and safety standards. These include sharing information with patients' primary care providers, using EHRs, referring patients without primary care physicians to these providers, making prices transparent, and using evidence-based guidelines.

CCA member clinics also are committed to patient follow-up. For example, nurse practitioners regularly call patients after visits—usually the next day—to check their status and confirm whether any prescriptions were filled. "The nurse will also take the opportunity to again encourage the patient to get connected to a primary care practitioner if they aren't already," Hansen-Turton said. "I think that is how we have gained a lot of credibility in the local medical communities where our clinics operate, because they are feeders now into primary care."

Charland believes that some physician groups oppose the expansion of retail clinics simply because of a concern over competition. "It's interesting that this argument against fragmented care only emerged when retail clinics came to be. I don't really buy this argument or the quality argument. I think it's purely economic. These are the bread and butter, easy visits for physicians. If it's fragmented care, it's been there for a lot longer than retail clinics have been, and it's fragmented because physician offices make it that way, by making it so inconvenient that people are forced to find alternatives."

Charland emphasized that he sees little difference between a physician overseeing a nurse practitioner in a doctor's office versus reviewing what nurse practitioners document after seeing patients in retail clinics. "When physicians have nurse practitioners in their offices, they certainly don't see every patient the nurse sees. So now with a retail clinic there is a nurse practitioner a quarter mile down the street. There is no difference than when the physician looks at a record after the fact for the patient in either case. This is an economic impact on the physician, no two ways about it."

No one has specifically studied the quality of testing at retail clinics. However, other CLIA-waived sites such as doctors' offices that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has studied do not have a perfect record. CMS began studying CLIA-waived testing sites in 2002, and found that more than 20% of those surveyed didn't perform quality control as detailed in manufacturers' instructions and 13% didn't even have these instructions. According to CMS, the agency continues to survey about 2% of CLIA-waived labs each year, and finds similar results. CMS has plans for a new educational program to try and improve upon these numbers.

With Expansion, More Testing Likely

Experts on retail clinics agree that services will continue to broaden, but what this will mean for diagnostics is uncertain. For the most part, retail clinics rely on CLIA-waived tests that they can perform on-site, and the small space and need for speedy appointments limits the kind of tests that can be performed.

Hansen-Turton noted that diagnostic companies regularly approach CCA seeking to find a place for their rapid tests. "A lot of different companies come to us from the diagnostic area, and we often bring them in to our members to get their thoughts," she said. "We try and help our members take advantage of some of these new technologies from diagnostic companies that can work within a very small footprint. We are going into a new expansion, and you will notice more growth and an evolution of services, but still within the framework of what can you do in a 15 to 20 minute visit."

More testing also goes hand-in-hand with the desire of clinics to enhance their offerings and avoid depending on services for which demand can come and go with the seasons, such as flu shots or children's sports physicals. "I think retail clinics in general would love to be able to provide more services, and certainly more tests would facilitate that," said Mehrotra. "The limitation is that usually they only have one nurse practitioner on site, and blood draws add a level of complexity."

Like the growth of other services retail clinics offer, payers ultimately will be the driving force behind more testing, according to Charland. "What will generate testing volume is insurance companies putting an incentive out there for people to go get tests—and that could be a carrot or a stick," he said. "In an ACO type of risk arrangement, where a health system takes on the risk of a population's health, they'll want to find ways to efficiently monitor chronic diseases. If that health system decides that MinuteClinic is the most efficient way to get that done, that's what will change it. It will be some sort of incentive for the patient. And we definitely see that starting to happen."

Courting the Walk-In Patient

As healthcare becomes more competitive, more patient-focused, and more sensitive to cost, retail clinics and other non-traditional outreach settings could be essential for health systems. "A key benefit of retail clinics run by health systems is that they serve as an entry point for new patients," Mehrotra commented. "Drawing new patients into their primary care and specialty system is critical."

With health systems and retail clinics experimenting with new services and new partnerships, the lines between urgent care centers, retail clinics, and other kinds of outreach settings also will blur, Charland predicted. "There used to be three unique markets, but there is now significantly more convergence as they compete with each other for that walk-in patient," he said. "And there is all kinds of activity in this space that I think is positioning it for the future, which is when we will no longer pay for healthcare mostly on a transaction-by-transaction basis, but instead will pay for outcomes, the ACO concept. If that really takes hold, the economic incentives change, and suddenly there is not a threat, but rather an incentive to find a way to get that illness treated in the most efficient way possible."