The lack of harmonization of clinical assays can seem deceptively remote to an individual lab. Laboratorians get to know their measurement procedures inside and out, jumping through numerous regulatory hoops and employing a variety of tools to assure quality. However, even proficiency testing surveys cannot always demonstrate significant problems among different measurement procedures. As a result, when a patient has the same test performed at more than one lab, results can shift due to differences among methods instead of the patient's own biochemistry, catching clinicians off guard.

A lack of agreement among different assays can compromise patient care on a wider level as well. Clinical practice guidelines that base recommendations on lab testing can be undermined by non-harmonized assays, reducing the effectiveness of evidence-based medicine and putting patients at risk.

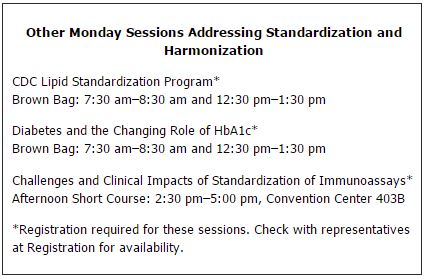

This morning, speakers will tackle this complex issue at the symposium "Method Harmonization: A Route to Improved Patient Outcomes" from 10:30 a.m.–12 p.m. in room 404AB of the Los Angeles Con-vention Center. The symposium will focus on the status of harmonization for clinical lab measurement procedures, and will explain how AACC's harmonization initiative is charting a course for a systematic and comprehensive approach to address the problem.

New Attention to an Old Problem

Most laboratorians are aware of standardization programs for certain well-recognized analytes, such as cholesterol or creatinine. These assays can be reliably traced back to a reference measurement procedure and standard reference material. This enables manufacturers to tie their kit calibrators used by the lab back to a recognized standard of scientific truth and keeps different methods from veering apart.

However, for many analytes and methods in the lab, standardization has not been realized. In some cases, a primary, pure substance cannot easily be defined because the analyte in questions is too complex. For example, many immunoassays produce results by recognizing different epitopes on the target analyte, unlike measuring a simple molecule such as glucose. For this growing list of more complex analytes, harmonization has become the goal. In this approach, panels of patient samples or commutable matrix-based reference materials may serve as the basis of aligning different methods through agreement to an all-methods mean or other technique.

Standardization and harmonization projects are expensive and technically challenging to accomplish. Nevertheless, it is an issue that can no longer be put off, according to Mary Lou Gantzer, PhD, the moderator at today's symposium and an independent laboratory consultant.

"One example that will resonate with anyone in the field is troponin I. Practice guidelines often quote specific cutoffs, despite the fact that troponin I is not standardized. That can potentially lead to harm to patients if a lab is using a method other than the one used to generate the data on which the cutoff is based," Gantzer said. "Having spoken with physicians at cardiology meetings who believe that they know a lot about biomarkers, when you ask them which troponin method they use, some will respond, ‘whatever they use in the lab.'" Efforts to standardize troponin I have gone on for more than a decade, Gantzer added. The International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC) Working Group, just one of several initiatives involving troponin I, also meets today here in Los Angeles to wrestle with standardization issues.

More examples of the risks to patients from non-harmonized and non-standardized assays will be presented at today's symposium by IFCC President Graham Beastall, PhD, FRCPath, from Laboratory Medicine Consulting in Glasgow, U.K.

The Commutability Conundrum

When an analyte cannot be traced back to a pure standard in the International System of Units, harmonization can still bring together divergent measurement procedures. This way, at least uniformity is achieved, and a patient sample will return the same result regardless of when or where the test is performed. However, if the reference material each manufacturer relies upon for calibration behaves differently than real patient samples —meaning that it is not commutable—each manufacturer's method may be traceable to that reference, but the results for patient samples are still discrepant among different measurement procedures.

As such, commutability is essential for any reference material to be useful. Commutability indicates that values measured for a reference material used as a calibrator and measured for native clinical samples have the same relationship between all the measurement procedures for which the reference material is intended for use. Consequently, even internationally recognized and certified reference materials may fail to achieve true harmonization if the materials are not commutable, Gantzer emphasized. "In the past, people have had a significant lack of understanding of the importance of commutability of reference materials," she said. "One problem we are facing is that people assume that certified reference materials from international organizations have demonstrated commutability, when in some cases they have not. When a reference material is not commutable, even though all manufacturers might trace their calibrators for their individual assays to that reference material, it really doesn't solve the problem because labs are going to get different results with different assays." This situation can be frustrating for diagnostics manufacturers, Gantzer added, since they do not always know what has been shown to be commutable and what has not.

A Global Effort to Improve Patient Care

Until recently, the lab community's harmonization problems have lacked a comprehensive and organized solution, especially for complex proteins and tumor markers. In response, beginning with an international conference in 2010, AACC has launched the Global Harmonization Initiative that will bring together a variety of stakeholders in the lab community to systematically select and prioritize harmonization projects. The AACC initiative will serve as the hub for connecting projects with funding and disseminating information to avoid any duplication of effort, and will incorporate advice from specialty societies and other stakeholders.

At this morning's symposium, AACC President Greg Miller, PhD, will lay out the progress that the AACC harmonization initiative has made since the 2010 meeting. Miller is a professor in the department of pathology and director of clinical chemistry at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

According to Miller, the AACC initiative will actively solicit ideas from stakeholders but will focus on analytes for which there are no higher-order reference measurement procedures. Miller, Gantzer, and others co-authored a paper in Clinical Chemistry describing the AACC initiative. The article offers several examples of tests that have complex molecular forms that lend themselves to harmonization, but for which a reference measurement procedure is not available (Clin Chem 2011;57:1108–1117). These include thyroid-stimulating hormone, human chorionic gonadotropin, prostate-specific antigen, troponin I, natriuretic peptides, carcinoembryonic antigen, luteinizing hormone, hydroxylated vitamin D vitamers, Epstein-Barr virus, and BK virus.

While AACC is supporting a steering committee and task forces to develop the infrastructure and technical operations of the harmonization initiative, implementation will require collaboration of international clinical and medical organizations, diagnostics manufacturers, clinical laboratories, metrology institutes, standard setting organizations, public health organizations, external quality assessment and proficiency testing providers, and regulatory agencies. Miller will explain how AACC will be reaching out to many of these stakeholders as the project continues to move forward.

The session is open to all registered attendees.