Even with an increasing number of high-tech tools available to hospitals, labs often struggle to optimize critical value reporting. One of the most challenging aspects of this issue is the volume of unanswered pages and forgotten callbacks from physicians, despite the fact that nearly 90% of physicians walk around with smartphones in their pockets.

In a rapidly changing information technology (IT) environment, lab results now compete with a swelling, cacophonous chorus of alerts and alarms that follow physicians throughout their day, often from the very electronic health records (EHRs) designed to streamline communications. According to experts who study patient safety problems, the only way to improve communication around critical values will be for laboratorians and physicians to work closely, pushing for smarter, comprehensive IT solutions that close the loop on follow-up for critical values and all abnormal results.

Labs must take a broader view of result reporting if they wish to improve communication with physicians, according to Corinne Fantz, PhD, a co-director of the core laboratories and director of point-of-care testing for Emory Medical Laboratories in Atlanta. "In an ideal world, all critical values would follow a single, clear definition and we would have simple, efficient ways to communicate with interested providers who respond quickly," she said. "But this is a pie-in-the-sky view of critical value reporting practices. Too often, labs focus on improving only what's within their control, optimizing individual pieces rather than looking at the whole process of caring for patients." Fantz, who is also an associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the Emory University School of Medicine, spoke during an October 16 AACC webinar, Improving the Efficiency of Critical Value Reporting: The Clinician/Lab Partnership.

A Frenetic Information Environment

Regulators and accreditors, such as The Joint Commission and the College of American Pathologists (CAP), define critical values as abnormal results that are life threatening and require a rapid response from caregivers. Both accreditors and the CLIA laws require written policies and procedures for critical value reporting, as well as complete documentation of the actions labs take. For example, if critical values are delivered by phone, labs must document whom they call and when, as well as request that the provider repeat back the information to assure accuracy. The danger for labs, however, is that they can become so single-minded about dispatching these results that their approach resembles a game of hot potato, according to patient safety expert Gordon Schiff, MD, who also spoke during the AACC webinar.

"That's fine if all we're interested in is a silo mentality," Schiff said. "But I think it's urgent that we all work toward a system that's better designed to work at both ends, instead of the lab waiting on physicians who don't call back pages, and the physician saying it's the wrong time to call or this isn't my patient." Schiff is associate director at the Center for Patient Safety Research and Practice at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

According to Schiff, in the same way that labs often feel great frustration when they are not able to reach physicians to release critical results, physicians increasingly feel overwhelmed with the high volume of alerts, calls, and other messages. What does it feel like for a primary care physician who is keeping up with abnormal test results? Schiff explained that primary care doctors compare their experience to Sisyphus, a figure in Greek mythology whom Zeus condemned to continually push a huge rock up a mountain, only to have it fall back down again.

Improving communication with physicians will require far more than just pushing out extra alerts, Schiff said. "The clinician will empty his queue of alerts and results in the EHR, and just a few hours later, it's full again," he said. "We need better electronic tools and a much more collaborative approach among labs and clinicians to do this right. Right now, information overload is replacing information dearth."

A recent study at the Houston Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) explored this problem. The researchers found that primary care physicians received, on average, about 57 alerts each day via EHR, and spent nearly an hour a day just processing these alerts (Am J Med 2012;125:209.e1-7). The alerts came from test results, referrals, notes, order statuses, patient change statuses, and incomplete task reminders. Notably, these were asynchronous alerts, such as abnormal lab results—not panic values called in from the lab—but the study describes the kind of alert-intensive environment modern electronic systems have created.

"Primary care providers appear to receive a large quantity of electronically delivered information each day and spend a significant proportion of their work day processing it," the authors wrote. "We previously found that about 7% of abnormal laboratory and imaging test result alerts were missed in EHR systems. Information overload from too many alerts might be a potential reason, given that practitioners must sort through a large number of alerts daily. This phenomenon has been described as ‘alert fatigue' and can lead busy practitioners to overlook critical information."

The authors noted that prior research has shown that physicians seem to be less efficient at managing electronic information compared to their ability to process paper-based information. And compounding this problem, the ease of introducing new information into an EHR seems to encourage institutions to make the problem worse. "Because it is far easier to create additional electronic alerts than paper-based ones, institutions might be more willing to keep adding new alerts to their EHRs to ‘improve' communication," the authors wrote. "Therefore, the potential for overload is greater because practitioners can more easily receive potentially unnecessary information they traditionally would not have."

In such a noisy information environment, Schiff emphasized that health systems will need to learn lessons from other disciplines such as engineering that have had to manage and prioritize critical communications. The literature in this field would suggest working toward a system that focuses on efficiency, standardization, and continuous measurement for improvement. As the IT environment becomes more complex, this kind of systems approach will require collaboration among clinicians, laboratorians, and other departments, he emphasized. If labs aim only as high as regulatory documentation requirements, or focus only on streamlining their own processes in isolation, the true goal of patient safety may be lost.

"We have to think about documentation as something we're doing to make the process work better, not just to cover ourselves," Schiff said. "It's not about getting things tidied up for the Joint Commission—though obviously those standards are important—but our documentation ought to be a byproduct of doing the right thing in the first place, which is tracking and auditing what we do so we can improve."

When individual departments of a hospital, for instance, tweak their processes without the entire system in mind, they create problems for themselves and for others. Referred to as sub-optimization, this happens when one process in a complex system works for one set of people at the expense of others, Schiff explained. Applying this to reporting critical values would mean that each department and lab should have the same kind of communication system for receiving and sending information. On the other hand, physicians should not expect the lab to tailor communication to their unique preferences beyond certain limits, and should agree to a standardized protocol, for example, as to when the lab can call and who will answer.

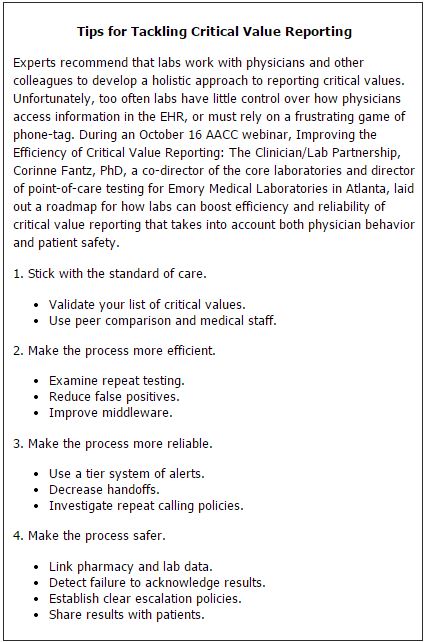

Fantz echoed Schiff's comments, noting that labs can improve critical result reporting by following well-documented best practices, such as validating their list of critical values, examining repeat testing policies, and adopting a tiered system for all abnormal values (See Box, below). She also recommended implementing algorithms that guide escalation steps in communicating with physicians, such as the one developed by Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, a researcher at the Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D and a co-author of the recent study on EHR alerts.

Working with Technology

To be sure, technology need not be the enemy. Pagers, for example, revolutionized communication between labs and physicians, and many labs depend on call centers focused entirely on this vector of communication for critical values. Recently, a systematic evidence review, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)'s Laboratory Medicine Best Practices Initiative, examined the literature on automated notification systems and call centers for communicating critical values (Clin Biochem 2012;45:979–87). Due to a paucity of high-quality studies on the subject, the authors did not make a recommendation on automated notification systems; however, they found a moderate overall strength of evidence in favor of recommending call centers as a best practice.

Based on five studies rated fair or good, the authors found that a randomly selected critical value would be reported by a call center faster than the lab 88.6% of the time. Fewer good quality studies looked at automated notifications. Automated systems in the study still relied on pagers, but notification went directly to the physician's pager after special software interpreted the value as critical. Instead of calling back the lab, physicians received a code on their pagers directing them to log into the EHR and check a result. The evidence review found that automated systems were faster than standard notification 61.8% of the time.

According to Edward Liebow, PhD, the lead author of the evidence review, labs should resist the temptation to compare the findings on automated notification to those on call centers, though both results are presented in the paper. "We're not able on the basis of the evidence to make any head-to-head comparisons here," Liebow said. "The major take away is that there are systems that labs can put into place to improve the timeliness and accuracy of reporting critical values. But none of them is perfect, and there is no magic bullet."

Despite the ubiquity of smartphones and tablets, some in healthcare are now thinking of ditching these pager systems entirely. A new breed of secure messaging systems available to physicians on their smartphones and tablets is now allowing more options and richer features far beyond what current pager systems are capable of. These systems offer security that normal cellphone text messaging lacks, and their two-way capabilities automate the kind of closed-loop system that patient safety experts have advocated.

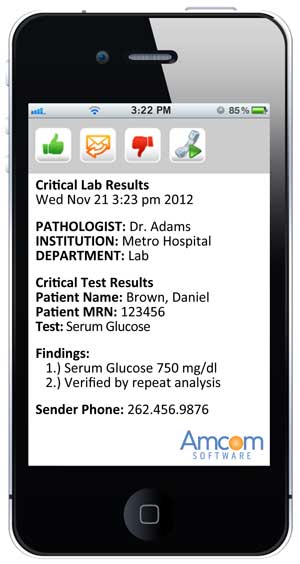

According to Brian Edds, the director of product strategy at the healthcare company Amcom Software, the future of critical value reporting will rely on mobile technology. "The crucial change that we're seeing in this space is that test results used to be a very manual, voice-based game. Our product is different in that it takes advantage of the move away from voice to two-way devices," he said. "This allows us to automate the outbound notifications and escalations and take advantage of smartphones so that people can securely receive those critical test results and then acknowledge that result with a simple click of a button. We're moving from a voice-based methodology to a message-based methodology and smartphones are really a key catalyst." Amcom's system works alongside a hospital's EHR, and connects to laboratory and radiology information systems.

Edds emphasized that these mobile-friendly solutions can keep critical results from falling through the cracks. They create an audit trail of message sending, delivery, and receipt, and labs can configure the software that escalates an alert when the initial caregiver does not respond in a timely manner. Amcom, which has developed communications software for hospitals for more than 30 years, began offering its new critical test result management product only this year in response to demand from customers, according to Edds. The software is also targeted to help hospitals meet the Joint Commission's 2013 patient safety goal 2, "getting important test results to the right staff person on time."

"Critical result management was an area where our customers—more than 900 hospitals across the country—told us they really had pains. They wanted to become more efficient and they were spending a lot of time with this game of phone tag with physicians," Edds said. "Obviously this has efficiency impacts from the radiologist's or the lab technologist's point of view, but it also has patient care impacts."

Amcom's critical test results management software

allows physicians to receive critical value alerts via special software on their smartphones.On the iPhone screen capture above, the person receiving the message would press the green thumbs up button to accept the message,

the orange envelope button to reply back to the message,

the red thumbs down button to decline the message,

or can instantly call back using the green phone button.

Don't Forget Sub-Critical Results

According to Schiff, who studies patient safety problems as well as malpractice claims around test results, hospitals need to improve their reporting of critical values, but sub-critical values may be an even bigger challenge. Sub-critical values usually will not show up on a critical value list in the lab, and generally do not require immediate intervention. But these lower-level abnormal results can still have a big impact on patients if they're ignored.

"These sub-critical values are really the hardest. We often do pretty well with panic values, but these less urgent abnormal values are high frequency but easy for physicians to miss," Schiff said. "I think that's where I would put my attention, and the malpractice data strongly supports that this is where the greatest risks are. Even though a critically high potassium may create a lot of anxiety and back and forth, the real problem is lurking where the light isn't shining."

For hospitals, a recent study exposed a major weakness for test follow-up. Australian researchers found that close to half of all tests ordered by physicians on the day of a patient's discharge were never reviewed, and more than 14% of the results were abnormal (Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1–2). Lead by Enrico Coiera, MD, director of the Centre for Health Informatics at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation, the researchers found that computerized provider order entry (CPOE) systems and improved EHR software could help solve the problem. "Even a simple list of test results that has not yet been read or has not yet come in could be generated electronically to prompt clinical teams to actively manage them, both on discharge day and in the days that follow," Coiera said.

Last year, a separate group of Australian researchers conducted a systematic review of test follow-up in ambulatory patients and found "substantial problems" (BMJ Qual Safe 2011;20:194–9). Failure to follow-up was as high as 61.9% for hospitalized patients and up to 75% for emergency department patients. One study the researchers reviewed found that nearly a third of critical biochemistry results during a 6-month period had not been accessed electronically. The authors found "evidence of a favorable trend toward reduced missed results" where IT solutions had been implemented, but noted that problems persisted in both paper-based and EHR-enabled institutions. "Technological solutions are not the entire answer," they wrote.

According to Singh of the Houston Veterans Affairs HSR&D research team, EHRs often come up short in addressing follow-up for sub-critical results. "Most of the EHRs are really quite far behind. However, lab results are now getting more attention as people look toward Stage 2 of the government's EHR meaningful use requirements, which emphasize test results reporting through the EHR," Singh said. "Using CPOE to order lab tests is the way to go. You can have all sorts of fancy processes in place, but unless the results get back to the right person, you're not going to have any follow-up on it. CPOE is the beginning point of getting the results into a trackable coded fashion that is recognized by the computer so that the communication loop can be closed." CDC recently convened a panel called the Communication in Informatics workgroup to tackle some of these problems, and has charged Singh and other experts on the panel with finding ways to optimize the use of lab data in EHRs.

Meanwhile, Singh cautioned that even with new technology and firm policies for physicians and labs, failure-proofing test follow-up is complex. Drawing clear lines for who is responsible to follow-up on abnormal lab results can be elusive, even when an organization's policy is unambiguous. "Even though institutions might make it clear that the ordering physician is responsible for all test results, people say well, that won't work because I'm an emergency medicine doctor who works in shifts, or, what happens when the hospitalist leaves after his shift," he said. "The fact is, people often do not follow written policy. We can preach, and bring this up as an issue everywhere and build awareness, but I think ultimately, we'll need even more advanced electronic tracking systems to ensure responsibility for follow-up. The computers will have to be able to figure out, based on who ordered a test, who is treating a patient, who is available, and how the notification should be routed."